Tour Stop 1 (101)

Introduction and The Hand of God

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840-1917)

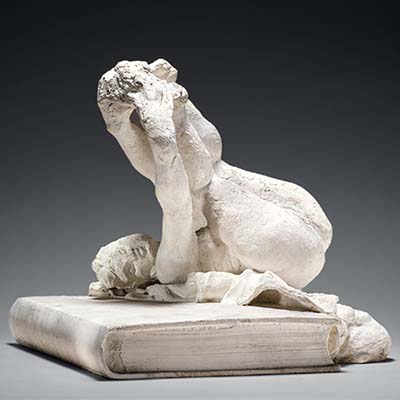

The Hand of God

maquette

1898, plaster

Paris, Musee Rodin. © Musée Rodin

Hello. My name is Mitchell Merling and, on behalf of Alex Nyerges, director of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, I’d like to welcome you to the exhibition Rodin: Evolution of a Genius. Organized by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and the Rodin Museum in Paris, this exhibition explores the creative process of the great sculptor Auguste Rodin, born in 1840.

Before we begin our visit, I’d like to say a few words about this audio guide. There are 21 stops written especially for our adult audience. To encourage the discovery of art for families, the Museum has included 10 comments for our young visitors. The comments for adults are indicated by a headphone icon. For children, look for an open book icon.

Until his death in 1917, Rodin produced a body of work that broke with the sculpture of his time. This exhibition is a unique opportunity to reflect on his artistic practice and understand its modernity. Through the proliferation of molds of his works, which he was constantly assembling, fragmenting, recycling, and modifying, he brought a new language to sculpture and created an innovative body of work which was shocking in its day but full of possibilities for twentieth-century sculptors.

There is nothing astonishing in a sculptor being fascinated by the hands. The hands are what shape and give life to the figures he imagines. They are the very instrument of his creativity. Hands have a special place in Rodin’s work. Presented on their own or attached to a body, Rodin’s hands are always expressive.

Even when unattributed, we are able to understand their identity or the situation they suggest. I would bet that you could find the two joined right hands entitled The Cathedral, for example. This is something the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, the author of a book on Rodin in 1903, understood quite well:

There are among the works of Rodin hands, single, small hands which, without belonging to a body, are alive. Hands that rise, irritated and in wrath; hands whose five bristling fingers seem to bark like the five jaws of a dog of Hell. Hands that walk, sleeping hands, and hands that are awaking; criminal hands, tainted with hereditary disease; and hands that are tired and will do no more, and have lain down in some corner like sick animals that know no one can help them.

And then there is The Hand of God. The hand that rises out of the barely roughed out block. The hand holding a material out of which emerges the intertwined and sensual couple Adam and Eve. Note the contrast between the smooth surface of the hand and the raw material of the block. This aesthetic choice of the unfinished, the non finito, unquestionably recalls Michelangelo, whom Rodin admired all his life.

To create this work, Rodin re-used the hand of Pierre de Wissant, one of the figures in his monument The Burghers of Calais, made fifteen years earlier. In that sculpture, the burgher’s raised hand expresses despair. Here Rodin gives it a completely different meaning. This recycling is a technique that we will see often in Rodin’s innovative work. The hand that shaped the first humans is the symbol of the supreme Creator. But does it not also symbolize the hand of the sculptor himself?

Before halting in front of the maquette of The Gates of Hell, I invite you to observe the large photograph of the work while listening to a few comments about it from the period:

There is in this young sculptor an originality and a tormented power of expression that is truly startling.

It’s a jumble, a confusion, a tangle.

Like a battlefield of quivering bodies.

The Gates of Hell is astonishing in its unfinished state.

What admirable despair.

Tour Stop 2 (102)

The Gates of Hell, third maquette

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

The Gates of Hell

Bronze

Alexis Rudier Foundry, cast 1928

©Musée Rodin

In 1880, when Rodin was 40 years of age, he was commissioned to create a monumental door for the future museum of decorative arts.

For his subject, Rodin drew on The Divine Comedy by the Italian poet Dante Alighieri. In this long fourteenth-century poem, Dante described his journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven. Rodin was enthralled by the circles of hell, inhabited by throngs of suffering creatures, and left out the other parts. Nevertheless, Rodin’s work is in no way an illustration of the poem, but rather a free and personal interpretation.

The Gates of Hell is the most important work in Rodin’s oeuvre. He worked on it for a number of years and subjected it to constant changes. He created more than 225 figures, using them like a reservoir of forms on which he drew for the rest of his career. As we will see in our visit, figures initially conceived for The Gates were often reworked and re-presented as autonomous sculptures.

Rodin initially envisioned the gate divided into panels, like the Gates of Paradise, created in 1452 by Lorenzo Ghiberti for the Florence Baptistery, which Rodin may have seen during his travels in Italy in 1877. The project changed, however, and Rodin abandoned this structure in favor of a door with leaves and pilasters topped by a tympanum. This organization enabled him to free himself from the low relief and to place in his door figures in the round, meaning in three dimensions. He created a crowd of sometimes difficult to identify figures, as you saw earlier in the photograph of The Gates. The leaves have the quality of an organic magma, a tumultuous tide of souls condemned to eternal punishment. In this third maquette, created a year or two after receiving the commission in 1880, we can see The Thinker, who dominates the scene, with The Kiss to the left and Ugolino and His Children to the right. I will return to these figures a little later on.

The Gates of Hell was exhibited for the first time in 1900, twenty years after it was commissioned. In the meantime, the project of building a museum of decorative arts, for which the work was intended, was abandoned. Throughout our visit we will see several sculptures designed for this project, which in the end remained unfinished. It was only after Rodin’s death in 1917 that bronze proofs of The Gates of Hell were cast.

Tour Stop 3 (103)

Fragments

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

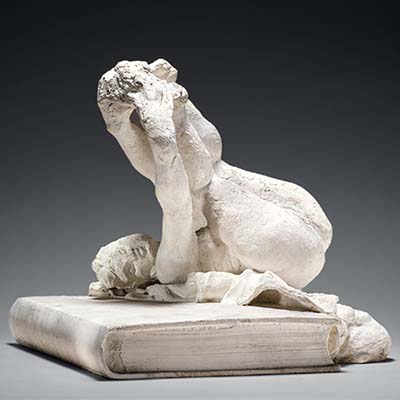

Ecclesiastes

plaster

before 1889

© Musée Rodin (photo Christian Baraja)

When Rodin presented a large retrospective of his work in 1900, on the sidelines of the World’s Fair in Paris, a critic noted the free and open arrangement of the pieces, in marked contrast with the rigidity of official sculpture exhibitions. The exhibition design gave the visitor “the impression of entering a studio.” Walk around this gallery while listening to the following commentary. In addition to these fragments, you can see several examples of assemblage and imagine that you are visiting Rodin’s studio.

Rodin had been acquainted with several studios. From the insalubrious and unheated former stable he rented in his youth to the large space lent to him by the French government in 1880, the studio was a place of toil and collaboration where materials, works in progress, and all the people needed to produce his work gathered. These included casters, specialists in pointing, stonemasons, and models. Rodin employed as many as fifty assistants in his studio. This creative space resembled a small business with its division of labor. Here Rodin conceived, tested, and created his works. Let’s listen once again to the poet Rilke, who visited Rodin’s studio in 1902.

There are gigantic showcases, entirely filled with wonderful fragments of the Porte de l’Enfer. It is indescribable. There it lies, yard upon yard, only fragments, one beside the other. Figures the size of my hand and larger . . . but only pieces, hardly one that is whole: often only a piece of an arm, a piece of a leg, as they happen to go along beside each other, and the piece of body that belongs right near them. Once the torso of a figure with the head of another pressed against it, with the arm of a third . . . as if an unspeakable storm, an unparalleled destruction had passed over this work. And yet, the more closely one looks, the more deeply one feels that all this would be less of a whole if the individual bodies were whole. Each of these bits is of such an eminent, striking unity, so possible by itself, so not at all needing completion, that one forgets they are only parts, and often parts of different bodies that cling to each other so passionately there. One feels suddenly that it is rather the business of the scholar to conceive of the body as a whole—and much more that of the artist to create from the parts new relationships, new unities, greater, more logical . . . more eternal. . . . And this wealth, this endless, continual invention, this poise, purity, and vehemence of expression, this inexhaustibleness, this youth, this still having something, still having the best to say . . . this is without parallel in the history of men.

These fragments and bunches of figures, these “limbs,” as he called them, were Rodin’s material. And their assemblage was one of the master’s practices, of which we will see several examples in this gallery.

Tour Stop 4 (104)

I Am Beautiful

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

I Am Beautiful

Assemblage of The Falling Man and Crouching Woman (for The Gates of Hell)

1882

Patinated plaster for bronze casting

69.5 x 36.3 x 36.2 cm

Paris, Musée Rodin © Musée Rodin (photo Christian Baraja)

The title of this couple, I Am Beautiful, was inspired by a poem by Charles Baudelaire, Rodin’s other source for the figures in The Gates of Hell.

I am beautiful, O mortals, as a dream in stone,

And my breast, on which every man has bruised himself in turn,

Is designed to inspire in poets a love

As eternal and silent as matter itself.

This is a good example of the kind of assemblage Rodin practiced throughout his career. Here he joins two figures who had been conceived separately. Look at the camber of the man’s body, arched by the effort of holding the woman in his arms. Note the contraction of the man’s back muscles and the assembled members of the woman’s curled-up body. The writer and art critic Edmond de Goncourt wrote:

Choosing at random from a heap of casts spread out on the floor, Rodin gives us a close look at a detail of his doorway. One of the most original groups represents his conception of physical love, but the concretization of his idea is not obscene. It shows a male holding against the upper part of his breast a female faun whose body is contracted and whose legs are drawn up in an astonishing similarity to the stance of a frog which is about to jump.

The sensuality of this figure and the somber eroticism it suggests made it very popular. Rodin re-used it in different sizes and materials. He went even further, however, when he employed only fragments of works, as can be seen in the Large Torso of The Falling Man also present in this gallery.

Tour Stop 5 (105)

Assemblage (Female Nude with the Head of Slavic Woman Emerging from a Vessel)

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840-1917)

Assemblage (Female Nude with the Head of Slavic Woman Emerging from a Vessel)

ca. 1900

plaster, terracotta

Paris, Musee Rodin. © Musée Rodin

His hands were extraordinarily broad with very short fingers. He kneaded the clay furiously, rolling it into balls or pellets, using both the palm and fingernails, tapping away at the clay, making it leap under his fingers, sometimes brutally, sometimes caressingly, wringing out a leg or an arm in a single gesture, or lightly brushing the flesh of a lip. It was a delight to see him at work. His mesmeric passes brought the clay to life.

These are the words of the author and friend of Rodin, Paul Gsell, watching a modeling session and describing the master’s method. This is how the small playful figures that Rodin made in great numbers in the last ten years of his life came into being. Several examples can be seen in this gallery. With this Female Nude Emerging from a Vessel, he took his assemblage method even further, joining an object from his vast collection of antiquities with a small female figure.

Rodin began quite early to collect sculptures and ancient objects from Egypt, Greece, and Rome. At the Villa des Brillants, his house in Meudon on the outskirts of Paris, he accumulated and displayed his vast collection. Made up for the most part of fragments, the collection was a constant source of inspiration. In the assemblages seen here, however, the collection becomes the very material of creation. This is a fine example of combinatorial art, the system of transforming through assemblage that was the basis of Rodin’s modernity.

The small figures that Rodin placed in vases and cups recall the analogy that he described to Paul Gsell:

At one moment, [a woman’s body] resembles a flower: the bending of the torso imitates the stem, while the smile of the breasts, and gleaming hair correspond to the blooming of the corolla. At another moment, it recalls a supple liana, a shrub with a fine and daring camber.

Doesn’t a woman in a vase now seem a little less absurd?

Tour Stop 6 (106)

She Who Was the Helmet Maker’s Once-Beautiful Wife

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

She Who Was the Helmetmaker's Once-Beautiful Wife

patinated plaster for bronze casting

1880-3

©Musée Rodin

The model for this poignant sculpture was a woman named Marie Caira. The writer Octave Mirbeau told her sad story. This eighty-two-year-old Italian woman came to Paris to see her son, who forced her to pose for artists to earn her keep. This is how she came to serve as a model for Rodin and for his collaborators Jules Desbois and Camille Claudel. Mask of Death by Jules Desbois is her. The Helmet-Maker’s Wife also.

Freed from The Gates of Hell, the sculpture of this gaunt, curled-up old woman strikes us with its uncompromising realism and its forceful expression. For Rodin, nothing in art is ugly, except what is false and artificial.

In art, only what has character is beautiful. Character is the intense truth of any natural spectacle, beautiful or ugly. My busts have often displeased because they were always very sincere. They certainly have one merit: truth. May this serve as beauty!

RODIN’S CREATIVE PROCESS

Here is how Rodin created a figure.

When I begin a figure I first look at the front, the back, the two profiles of left and right, that is, their contours from four angles; then, with clay, I arrange the large mass as I see it and as exactly as possible. Then I do the intermediate perspectives, giving the three-quarter profiles; then, successively turning my clay and my model, I compare and refine them.

This way of approaching the model, which he called his theory of profiles, was a constant in his practice. This is how he remained faithful to nature and achieved the truth of the figure. While physical resemblance was important to him, he sought most of all to express the character of the model, his or her inner life and soul.

Everything in nature is beautiful, because it’s living . . . Beauty is life, whatever its form.

Tour Stop 7 (107)

Mask of Hanako, Type E

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

Mask of Hanako, Type E

Between 1907 and 1910

Terracotta, plaster

18 x 12 x 14.4 cm

Paris, Musée Rodin © Musée Rodin (photo Christian Baraja)

Hanako means “little flower.” This was what the Japanese actress was called by the American dancer Loïe Fuller, who introduced her to Rodin in 1906. She had come to Marseille for the Colonial Exposition, and impressed Rodin with her strength and suppleness. He invited her to pose for him, and made more than fifty masks and busts of her, along with several drawings, a few examples of which can be seen here. The muscular strength of the “exotic” body of this quite small actress struck Rodin, who told Paul Gsell:

She is so strong that she can stand as long as she likes on one leg while raising the other before her at a right angle. Standing this way, she looks as if she were rooted to the ground like a tree.

Hanako could contract her face into expressions of rage and hold the pose for hours. She was moving and highly expressive when acting scenes of hara kiri; this mask in molten glass depicts instead a moment of rest between two posing sessions. Hanako used the expression “meditative woman” to describe this work. Relaxed, her mouth slightly open and her eyes blank, her face expresses rest and reverie.

The specialist Jean Cros participated in the creation of the sculpture in this material. Used since antiquity, molten glass replaced the plaster in a special mold before being fired. Rodin used this material for portraits of women because it produced a color resembling skin tone.

Tour Stop 8 (108)

Balzac

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840-1917)

Balzac, with a broad lapel on the dressing gown, penultimate study

1897, cast 1962, bronze

(Georges Rudier Foundry), Edmonton, Art Gallery of Alberta, gift of Westburne International Industries, 1978.

The sculptures of Balzac in this gallery give us a sense of Rodin’s processes when he creates a work. We are looking at Penultimate Study with a Broad Lapel on the Dressing Gown, a version very close to the final work. Feel free to move around from one sculpture to another as I tell you the story of this monument and the immense controversy to which it gave rise.

In 1891, the writer Émile Zola, president of the Société des gens de lettres, commissioned Rodin to create a monument in memory of the great writer Honoré de Balzac. Rodin began carrying out intensive research. He visited Tours, Balzac’s birthplace. He read his correspondence and his writings. He consulted painted portraits and photographs. He sought out models resembling Balzac, with the novelist’s corpulence. He even asked Balzac’s tailor to make him the famous dressing gown in which Balzac wrote. Rodin coated it with plaster in order to reproduce exactly Balzac’s imposing silhouette. In 1859, Balzac’s friend Théophile Gautier had written the following about this famous garment:

What fantasy pushed him to choose, over another, this dress, which he never took off? We don’t know. Perhaps it symbolized in his eyes the monastic life to which his labors condemned him and, as the Benedictine of the novel, he adopted its robe.

The Nude Study present in this gallery was submitted to the client in 1892. The statue was deemed indecent and rejected. Forever unsatisfied, Rodin constantly delayed presenting another sketch to the Société. As the years passed, a more personal conception of the subject took shape in Rodin’s mind. From a naturalist representation, Rodin simplified more and more.

“I strove to enlarge my art, to achieve simplification, which is true grandeur,” he said.

In the Penultimate Study, all the expressiveness is concentrated in the head. The corpulent man is draped in a dressing gown with stylized folds which conceals his misshapen body. Our gaze is directed towards the head, whose features have been exaggerated. More than a realistic or literal representation, Rodin’s monument is a moral portrait, which pays tribute to Balzac’s creative power and the vastness of his work. This revolutionary monument caused a scandal. Polemics broke out and criticism was fierce. The work’s detractors described its vision of Balzac as a “sack of coal,” a “penguin,” a “misshapen mass,” an “obese monster,” a “colossal fetus,” in sum, a “thing without a name.” The Société des gens de lettres rejected the monument. Deeply hurt, Rodin nevertheless remained persuaded of the value and importance of his Balzac. He said:

If truth must die, my Balzac will be broken into pieces by future generations. If truth is imperishable, I predict that my statue will make its way. This work that has been laughed at, that people have taken the trouble to jeer . . . is the logical outcome of my entire life, the very pivot of my aesthetic. From the day I conceived it, I was another man.

Rodin never saw his work cast in bronze. It was only in 1939 that the monument was installed at the corner of Raspail and Montparnasse boulevards, where it can still be found today.

Tour Stop 9 (109)

Meditation

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

Meditation, small version

About 1885

Patinated plaster for bronze casting

60.5 x 32.1 x 29 cm

Paris, Musée Rodin © Musée Rodin (photo Christian Baraja)

This represents a beautiful young woman whose body is painfully twisting. She seems prey to some mysterious torment. Her head is sharply bent. Her lips and eyelids are closed, and she seems to sleep. But the anguish of her features reveals the dramatic conflict of her spirit. What completes our surprise, when we look at it, is that she has neither arms nor legs. You cannot help regretting that such a powerful figure is incomplete. You deplore the cruel amputations to which she has been submitted.

That was Paul Gsell recounting his first impression of Meditation in Rodin’s studio. Rodin replied:

Why are you reproaching me? Believe me, I left my statue in this condition on purpose. Haven’t you noticed that when reflection is carried very far, it suggests such plausible arguments that it recommends inertia?

This Meditation, without arms, was exhibited in Dresden and Stockholm in 1897, but it was very poorly received because of its incomplete state. The poet Rilke understood this deliberate fragmentation on Rodin’s part.

It is striking that the arms are lacking. Rodin must have considered these arms as too facile a solution of his task, as something that did not belong to that body which desired to be enwrapped within itself. . . . The same completeness is conveyed in all the armless statues of Rodin; nothing necessary is lacking. One stands before them as before something whole.

The three Meditations shown here are fine examples of Rodin’s creative labor as he conceived, reworked, enlarged, and fragmented a figure. Created initially for The Gates of Hell, Meditation later became an Inspiring Muse in the Monument to Victor Hugo before taking on its own life, isolated and exhibited on its own.

Tour Stop 10 (110)

Thought (Portrait of Camille Claudel)

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

Thought (Portrait of Camille Claudel)

plaster, cast after the marble

1893-95

©Musée Rodin

Thought is an example of a sculpture in which the block is an integral part of the work. Rodin contrasts the smooth, well-polished material with the parts left in a rough state. Out of the oversized and quickly hewn material emerges the head of a very beautiful young woman. Her inclined head is covered with a cap. Her chin rests on the block and her eyes are lowered. The work we are looking at is in plaster, molded from the marble sculpture. The model is Camille Claudel, an artist and great love of Rodin’s in the 1880s. She fascinates us still today. Her tragic destiny and messy, interrupted life are still moving, and with cause.

Camille Claudel entered Rodin’s life around 1882, at first as a student and then as an assistant in his studio. She was 18 and he was 45. Rodin quickly realized her great talent, later calling her a brilliant artist.

Beginning in 1882, she regularly exhibited busts and portraits of her friends and family at the Salon. As his inflamed letters show, Rodin fell head over heels in love. “I love you horribly,” he wrote to her. Between two sculptures which she executed for him, she posed for a few of his works. She worked in Rodin’s studio for five years before devoting herself exclusively to her own work.

In 1893, after ten years of relations with Rodin and exasperated by his refusal to leave Rose Beuret, his long-time companion, and falling victim to a mental illness which rendered her paranoiac, she broke with Rodin, accusing him of wronging her in every possible way. Rodin recovered with great difficulty, as seen in his correspondence. Nevertheless, he continued to watch over her from a distance. Her family hospitalized her in 1915, and she died in this same institution thirty years later in 1945. This internment was the end of her career.

Is Thought a metaphor for the life of Rodin’s lover? Confined in her illness the way the figure’s body is prisoner of the block of marble? A head that thinks but an absent body, unable to act? Or, on the contrary, is it the symbol of unlimited possibility? Doesn’t the half-finished figure give the illusion that every hope is permissible?

Tour Stop 11 (111)

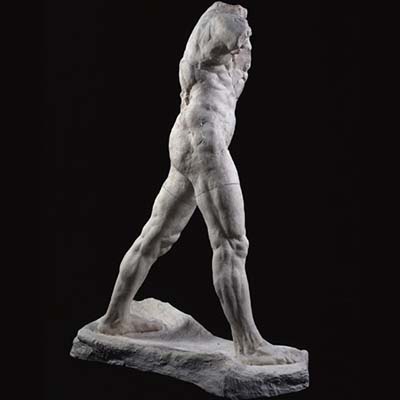

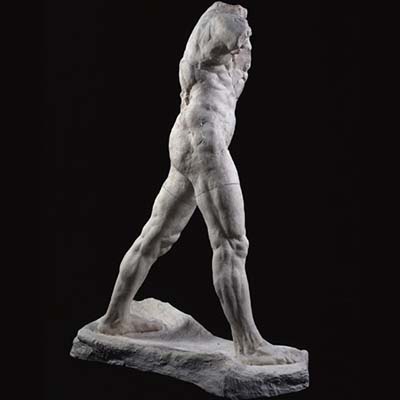

The Walking Man

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

The Walking Man, large version

1907

Patinated plaster

218.3 x 160.2 x 74.9 cm

Paris, Musée Rodin © Musée Rodin (photo Adam Rzepka)

This Walking Man is an example of the fragmentation and assemblage underlying Rodin’s modernity. Initially presented in a reduced version, perched on top of a column in his retrospective exhibition in 1900, this work was not remarked upon. The enlargement you see here breathed new expressive force into the statue. Created twenty years after the Saint John the Baptist which we are about to see, this work is the result of an assemblage of a study of legs and a torso, which was probably also connected with this figure. Finding it cracked and damaged after years of neglect, Rodin left it as it was, so that the torso contrasts with the smoothness of the legs. The crevasses in the armless and headless torso accentuate the reference to fragments from Antiquity.

Rodin remarked: “People have often reproached me for not putting a head on my Walking Man. Does one walk with one’s head?”

The Walking Man is often seen as the very symbol of pure creation, without reference to any subject in particular. Through this absence of references, alongside the obvious assemblage that Rodin makes no attempt to conceal, this sculpture unquestionably asserts one of the innovative aspects of his work.

Tour Stop 12 (112)

Saint John the Baptist Preaching

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

Saint John the Baptist Preaching

medium-sized version, Plaster

1878

©Musée Rodin

This is the Saint John the Baptist whose molds were used for the creation of The Walking Man. But it is a very different Saint John the Baptist from traditional depictions of the holy man, for here the man who announced the coming of Christ is wearing neither the camelhair tunic nor the reed cross, which usually enable us to identify him. He is naked and retains only the gesture of the raised hand suspended in space. Very early on in his career, Rodin had done away with anything that appeared superfluous to him. The previous year, at the 1877 Salon, he had presented a life-sized nude, which was so perfect that he was accused of having molded the body of his model. To silence these suspicions, Rodin created Saint John the Baptist in a larger than life format. Here is Rodin explaining how he got the idea for this figure the day an Italian peasant from Abruzzo, Pignatelli, came to see him to offer himself as a model:

Seeing him, I was seized with admiration: that rough, hairy man, expressing in his bearing . . . all the violence, but also all the mystical character of his race. I thought immediately of a Saint John the Baptist; that is, a man of nature, a visionary, a believer, a forerunner come to announce one greater than himself. The peasant undressed, mounted the model stand as if he had never posed; he planted himself, head up, torso straight, at the same time supported on his two legs, opened like a compass. The movement was so right, so determined, and so true that I cried: “But it’s a walking man!” I immediately resolved to make what I had seen.

This quotation highlights two things: the importance of the model, who suggests the pose, and the desire to express movement through rest, the ultimate goal of all of Rodin’s art.

Tour Stop 13 (113)

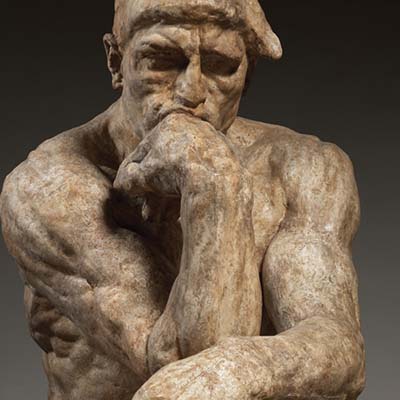

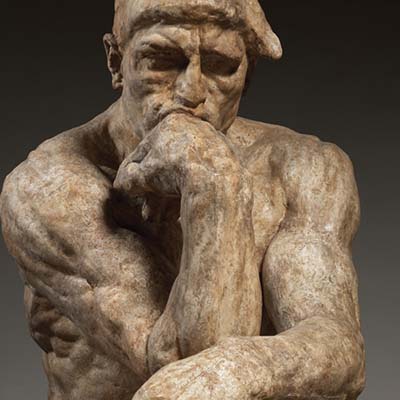

The Thinker

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

The Thinker, large version

1903

Patinated plaster for bronze casting

182 x 108 x 141 cm

Paris, Musée Rodin

© Musée Rodin (photo Christian Baraja)

Along with The Kiss, The Thinker is probably Rodin’s best-known sculpture. From the beginning of The Gates of Hell project in 1880, Rodin foresaw this figure at the summit of the door in the tympanum. This, moreover, was the sole unchanging element of this frequently modified work. At first it was the poet Dante, author of The Divine Comedy, who contemplated the dramatic spectacle unfolding below. Like many figures in the Gates, The Poet, which later became The Thinker, had an autonomous existence. Initially 71 centimeters in height, the sculpture was enlarged to this colossal version, which indisputably heightened its expressive power. After 1900, as Rodin began to exhibit his work in numerous major international exhibitions, he commissioned an increasing number of enlargements of his sculptures. This difficult task was entrusted to the specialist Henri Lebossé. In the nineteenth century, several inventions made it possible to mechanically enlarge or reduce the size of a sculpture. A proof of this large Thinker was given to the city of Paris and placed in front of the Pantheon from 1906 to 1922. Since that date, the sculpture has been on exhibit in the gardens of the Rodin Museum.

Seated on a rock, a powerfully built man with tormented features and unkempt hair reflects. His athletic body is reminiscent of sculptures by Michelangelo. Note the contrast between the contractions of the muscles, suggesting effort, while the pose indicates reflection. Rilke, admiring the work, remarked:

He sits absorbed and silent, heavy with thought: with the strength of an acting man he thinks. His whole body has become head and all the blood in his veins has become brain.

But not every critic was so full of praise. It is difficult today to picture the hostile reactions to The Thinker when it was installed in front of the Pantheon. Many found it vulgar and too massive. The figure was described as a gorilla and a brute. His position was ridiculed, giving rise to scatological caricatures.

But who is this Thinker? Who is this man? Is it really Dante thinking about his Divine Comedy, or Rodin himself conceiving his work? Rodin said: “He’s not a dreamer, he’s a creator. I made my own statue.”

This was the work, moreover, that was placed on Rodin’s tomb in 1917.

Tour Stop 14 (114)

Ugolino and His Children

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

Ugolino and His Children on a Column

plaster

1882

©Musée Rodin

The question of pedestals was of keen interest to Rodin, who made use of all their possibilities. A pedestal supports the work, brings it into view and protects it. With Rodin, the pedestal became an integral part of the work. He presented Ugolino and His Children on a column in the retrospective of his work in 1900. A few examples of this kind of presentation can be seen in this gallery, including Left Foot of the Thinker and the bust of Madame Fenaille, whose pedestal is also cast in bronze. Initially conceived for The Gates of Hell, as we saw in the maquette at the beginning of our visit, Ugolino and His Children was separated from it and became an independent work. The subject, taken from The Divine Comedy, recounts the punishment suffered by Ugolino, a thirteenth-century Italian count. After having governed through terror, he is condemned for treason and imprisoned with his four sons. Driven mad with hunger, he is reduced to the state of an animal. Legend has it that he ate the flesh of his children. This is what Ugolino’s humiliating pose suggests here with such force. Here is how Paul Gsell described the emotion this work created in him when he visited the exhibition:

This is a figure of grandiose realism. It does not recall at all the group by Carpeaux: it is even more pathetic, if this is possible. In Carpeaux’s work, the Pisan count, tortured by rage, hunger, and the pain of seeing his children near death, bites both of his fists. Rodin has shown the drama at a later moment. The children of Ugolino have died. They lie on the ground, and their father, changed to a beast by his hunger pangs, crawls on his hands and knees over their cadavers. He leans towards their flesh, but at the same time violently throws his head to the side. In him is let loose a terrible conflict between the brute who wants to eat his fill and the thinking being, the loving being, who is horrified by such monstrous sacrilege. Nothing is more poignant!

Tour Stop 15 (115)

The Three Shades

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

The Three Shades, small version (for The Gates of Hell)

1897

Patinated plaster for bronze casting

97.4 x 95.6 x 52.1 cm

Paris, Musée Rodin © Musée Rodin (photo Christian Baraja)

Rodin was first and foremost a modeler and not a stonemason. He modeled his figures in clay on a wood and metal frame. The work was then given to the caster, the specialist who made the mold which produced one or more plasters in exact imitation of the modeling. Rodin always demanded several moldings of the same work in order to modify it or re-use it as he pleased, according to his needs. In the case of The Three Shades, he placed three identical molds in such a way as to offer three different points of view of the figure. In this technique of multiplication, which Rodin used frequently, repetition of the figure gave rhythm to the whole. The technique is reminiscent of photographic experiments of the day, like those of Étienne-Jules Marey or Muybridge, who analyzed movement through a series of photographs.

Rodin made The Three Shades to sit at the summit of The Gates of Hell. Initially, he had planned to place Adam and Eve on each side of the Gates, an idea he abandoned in favor of The Three Shades. Nevertheless, the figures preserve the afflicted posture of Adam, which you can see in this gallery. They are the condemned souls of Dante who stand by the gates of Hell and say: “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.”

With their stooped heads and hands pointing downwards, The Shades watch the dramatic spectacle unfolding below them. This despondency, this pose of suffering, is incontestably reminiscent of Michelangelo.

Tour Stop 16 (116)

The Poet and The Siren

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

The Poet and The Siren (maquette)

plaster

1909

©Musée Rodin

We are now standing before The Poet and the Siren, a marble carved by Curillon in 1909. Once again, let’s take advantage of the work in plaster to compare the two works in two quite distinct materials, but especially to observe the modifications made by Rodin when the time came to transfer the work to marble. We see a nude woman bent forward and a seated nude man, leaning back with his right arm raised. To make the woman a siren, Rodin added plaster to her feet.

The base of the work is irregular and may be an allusion to the waves of the sea, the natural habitat of these half-woman, half-fish goddesses. In marble, The Siren is even more engulfed in the material and the base is much more imposing. Once again, Rodin contrasts the smoothness of the figures with the rough quality of the block. The variations between the plaster and the marble demonstrate that for Rodin artistic creation was a constantly evolving process.

Tour Stop 17 (117)

The Sirens

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

The Sirens

Before 1887

Marble, Jean Escoula practitioner, between 1889 and 1892

44.5 x 45.7 x 27 cm

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, gift of the Huntly Redpath Drummond family

Photo MMFA, Jean-François Brière

Part woman, part fish, sirens and their moving songs send sailors off course, shipwrecking them on the rocks. In Homer’s Odyssey, Ulysses plugs his companions’ ears with wax and has himself tied to the mast of his ship so as not to succumb to their songs. This is another work that was originally conceived for The Gates of Hell. The Sirens is also found among the earliest projects for a monument to Victor Hugo. It was enlarged and exhibited on its own with a base suggesting the natural element in which sirens live. Very popular because of its sensuality, the group was also transferred to bronze.

Tour Stop 18 (118)

Eve

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

Eve

Marble

c. 1883

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Frank P. Wood, 1928

© Art Gallery of Ontario

As we saw earlier, Rodin planned to place Adam and Eve on either side of The Gates of Hell, an idea that he abandoned in favor of The Three Shades. Eve then took on a life of its own in a variety of materials and on different scales, as we can observe here. We should note from the outset that Rodin did not carve his marble sculptures himself. He was a modeler, not a stonemason. He employed several pointers for this practice, to whom he nevertheless gave very precise indications. He was the one who decided the sculpture’s final appearance, supervising the work at every stage. Delegating the work’s transfer to marble to a stonemason was a common practice in art history after the Renaissance. Ever since Leonardo da Vinci defined art as a cosa mentale, the work of art has been defined by its conception and not its manufacture. It was only in the twentieth century that sculptors such as Brancusi and Henry Moore returned to carving the work directly themselves.

Have a little fun and compare Rodin’s plaster with the two versions in marble carved by pointers. Are there as many details, is the model the same, does the pose vary? Note the support behind the marble figures, missing in the plaster, and the tightening of the members compared to the plaster. These are some of the new qualities that appeared in Rodin’s marble statues in the late 1890s.

Rodin shows Eve after the fall, when she is ashamed and conscious of her nudity, which she tries to conceal. In the Christian tradition, Eve was responsible for the original sin and thus for the ills that befell humanity. Her folded arms and her face almost hidden in her bent left arm express the shame she felt when she and her companion were driven from their earthly paradise. When it was exhibited in 1882, the figure’s sensuality ensured the public’s favor. To meet demand, Rodin made several copies in bronze and marble. The young woman who served as a model for Eve was one of Rodin’s favorites. She was an Italian from Abruzzo named Adèle, “a magnificent woman of savage force whose movements were quick and feline, with the suppleness and grace of a panther,” Rodin related. He preferred amateur models because they were more spontaneous and did not assume the conventional poses of traditional studios. He told them: “Don’t pretend to brush your hair, brush it.”

Tour Stop 19 (119)

The Kiss, reduction No. 1

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

The Kiss, reduction No. 1, master model

1898

Bronze, Barbedienne Foundry, cast 1898

71.1 x 42.5 x 45 cm

Paris, Musée Rodin

© Musée Rodin (photo Christian Baraja)

If you have ever had a chance to visit the Rodin Museum in Paris, you will have seen the large marble statue of this famous Kiss. Originally, in the size it appears here, this couple was conceived for the large Gates of Hell project. The sculpture depicts the kiss between Paolo Malatesta and Francesca da Rimini the moment they became aware of their love for each other. Caught unexpectedly and killed immediately by Francesca’s husband, they were condemned to wander for eternity in hell in the story told by Dante, the Tuscan author of The Divine Comedy. In the end, Rodin decided to withdraw this group from The Gates of Hell because its depiction of a moment of pure happiness was incompatible with the tragic vision of hell he wished to impart.

Exhibited as an autonomous work in the fall of 1887, The Kiss was very successful and the French government commissioned a larger version in marble, which Rodin delivered ten years later. The large version of The Kiss was exhibited in 1898 with the statue of Balzac. By exhibiting his big knick-knack, as he himself described his Kiss, alongside the shocking statue of Balzac, Rodin may have been trying to reassure visitors to the exhibition with a work he knew to be more traditional.

Rodin sold the reproduction rights to The Kiss to the caster Ferdinand Barbedienne. Their contract set out the size of the sculptures, but placed no limit on their number. The bronze you see here is what is known as a master model. Barbedienne used this bronze, rather than the plaster model, to reproduce the sculpture, because the latter loses its sharp features after a few uses. The proofs made from bronze master models are of very high quality.

POSTHUMOUS BRONZES

The Rodin Museum in Paris was founded in 1919, two years after the death of Rodin, who had left his entire oeuvre to the French state, but with no directive concerning the reproduction of his work. At that time, there was no legal provision limiting the number of casts of original editions. Numbering casts is a very recent phenomenon, and it is impossible to trace the production of bronzes as far back as the end of the Second World War. Since 1981, the casting of so-called original proofs has been limited to twelve copies made from the same mold, four of which are not for commerce. The law makes no distinction between bronzes made during the artist’s lifetime and those cast after his or her death, on condition that they be made from original molds. The Rodin Museum produces five works each year, with eight copies of each. In conformance with the law, the works are numbered 1 to 8 and bear the museum’s copyright, the foundry mark, and the date of the casting. Four additional proofs are made for cultural institutions. The casting is always made from an original made during Rodin’s lifetime or, in certain cases, from a mold made from another bronze.

Tour Stop 20 (120)

The Defense, or The Call to Arms

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

The Defense, or The Call to Arms

1879

Bronze, Léon Perzinka Foundry, cast 1899

111.7 × 64.5 × 43 cm

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, purchase, Horsley and Annie Townsend Bequest

This work was sold by Max Stern, Dominion Gallery, Montreal (1961)

Photo MMFA, Jean-François Brière

This sculpture, called The Defense, or The Call to Arms, has been a part of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts collection since 1961.

Although there is no mark by the caster, we know that it was made by the caster Léon Perzinka. This craftsman, who worked alone in his foundry, began working with Rodin in 1896. This is the version that was exhibited in 1900 at the Alma pavilion. As was often the case, the sculpture was made out of several sections, which were joined after the casting. Perzinka himself made the joints to solder the parts together, and also the patina, steps usually carried out by specialists known as chasers and patinators. If you are a close observer, try to find the joints in the figures and determine the number of pieces used in casting this monument. Compare the two Defense statues if you like. The second casting was done fifteen years later by the Rudier foundry, Rodin’s other principal collaborator.

Unlike most sculptors of his time, Rodin followed the casting and patinating process with care and vigilance. This is confirmed in a letter by Rodin, who remarks concerning one of his sculptures that “She is simply what I modeled. The bronze chaser, under my order, never touches my model.”

This explanation is necessary to understand that the broken wing was an aesthetic choice of Rodin’s and not a defect in the casting.

HISTORY OF THE DEFENSE OF PARIS IN MONTREAL

In 1879, the Paris city council launched a competition to commemorate the heroic resistance of Parisians during the Franco-Prussian war of 1870. Rodin focused on the anger and energy of the allegorical figure of Liberty, reminiscent of the sculpture The Departure of the Volunteers of 1792 by François Rude. Liberty, wearing a Phrygian cap, rears skywards. She lets out a piercing cry, clenches her two fists and bats her wings. The soldier’s body has collapsed at her feet. The contrasting direction of the two bodies’ lines gives the sculpture vigor and dynamic expression. The bent left leg and the crumpled body of the dying soldier recall the Florentine Pietá that Michelangelo sculpted for his own tomb. His left arm weakly holds a broken sword. The surfaces were succinctly modeled and the soldier’s face lacks detail. The sculpture, however, was turned down. The subject’s treatment shocked the jury and prompted their rejection. The sculpture was not the heroic depiction that had been sought by the government. Enlarged to twice its size, the sculpture was finally cast in bronze in 1919 and then given to the city of Verdun.

The Defense held by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts is the version shown at the Alma pavilion in Paris during the Rodin retrospective in 1900. At the end of the exhibition, the sculpture left Paris for Vienna, where it was acquired by the collector and industrialist Ferdinand Block-Bauer. When Austria was annexed by the Third Reich in 1938, it was purchased dirt cheap by the director of the Dresden Museum, charged by Hitler with establishing the collection of his future museum in Linz. Hidden in a salt mine in 1941, it was rediscovered intact in 1945, when the right holders began the process of restitution of their uncle’s collection after his death that year. In 1948, The Defense was restored to the niece of Ferdinand Block-Bauer, Luise Gattin, then living in Vancouver. Luise Gattin decided to sell the sculpture in 1960. Thanks to the insistence of Max Stern of the Dominion gallery, it was acquired by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Tour Stop 21 (121)

Jean d’Aire (for the Monument to the Burghers of Calais)

Image: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

Monument to The Burghers of Calais in the garden of the Musée Rodin

1889

Bronze

Alexis Rudier Foundry, cast 1926

©Musée Rodin

Allow me to introduce you to Jean d’Aire and, right next to him, Eustache de Saint-Pierre and Andrieu d’Andres, three of the six figures who make up the monument The Burghers of Calais. Before speaking about Jean d’Aire, I’d like to tell you the story of this monument. In 1885, the city of Calais commissioned a monument to commemorate the heroic acts of the residents of Calais during the Hundred Years’ War. During the siege of the town in 1347 by King Edward III of England, he offered to spare the city if six notables were yielded up to him, dressed in sackcloth and bare feet and with a rope around their neck, to present him with the keys to the city. Rodin chose the moment of greatest tension, when the six burghers were convinced that they were going to their deaths.

These larger than life figures are shown with individual features. Only their heroic decision unites them. Unlike many public monuments of the day, the group is not shown in an imposing pyramid structure, but rather horizontally. The contrast between the men’s noble gesture and the simplicity of their depiction creates the group’s powerful expressiveness.

I hope you have enjoyed this visit to Rodin’s studio. We invite you to continue your exploration of sculpture by visiting the many examples on view in the permanent collections of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.