Two sofas arrived at the VMFA in 1954 with no stamps, no painted inscriptions, and no labels. Through extensive research, their design and specialized process in which they were made led them to be credited to artisan John Henry Belter. The sofas’ history goes back much further than the VMFA’s acquiring of them.

The sofas were made around 1850 by the shops of Belter using his particular wood lamination method of fusing together six or more thin layers of rosewood veneer that could be deeply carved. Both sofas feature detailed decorations on their crest or top rails; one features roses, the other a basket of mixed flowers. Almost eight feet wide, the sofas are large and extravagant, as was the trend during the mid-19th century.

From Belter’s shop, the next known owner of the sofas was John Roll McLean, a man who had grown rich from owning The Washington Post and The Cincinnati Enquirer. From whatever time he acquired the sofas, the wealthy fellow had the sofas and kept them in his mansion, despite the style of sofas having become dated by the time he put them into his house in 1907. At some point, before the two sofas were put into McLean’s mansion, they were gilded so as to complement the tastes of the Gilded Age. After McLean’s death, the couches and all his property went to his son Ned McLean and daughter-in-law Evalyn, who used the sofas in more opulent manner than the elder McLean ever had. The couple threw parties and receptions in the roaring twenties, during the height of the Jazz Age. The sofas often held Senators and society’s most elite members. However, Ned and Evalyn had marital problems and ended up separating and shortly thereafter, Ned died. Evalyn took the sofas with her to her new home in Washington, D.C. where she continued to use them at her own events until she passed away in 1947.

Many of Evalyn’s possessions went to public auction after her death. The sofas sold to Bessye “Polly” Morrison in 1948, who gave them to the VMFA six years later. The two sofas entered the museum as gallery seating furniture, not as collection acquisitions. Their 23 karat gold leaf was restored and seat coverings were replaced, as they had deteriorated over time. It wasn’t until later that they became objects for display and not until 1997, when the museum began a reupholstery campaign, that the original surfaces were tested. It was discovered that another layer of varnish existed under the gilding, suggesting that the gilding came after the original surface was completed. After a few years delay, it was decided to restore one sofa to its original 19th century appearance and the other to its appearance in the 20th century. The gilded sofa with the basket on the crest rail was cleaned and in-painted and in-gilded where necessary and went on exhibition in a new gallery while the other one went to conservation.

Many of Evalyn’s possessions went to public auction after her death. The sofas sold to Bessye “Polly” Morrison in 1948, who gave them to the VMFA six years later. The two sofas entered the museum as gallery seating furniture, not as collection acquisitions. Their 23 karat gold leaf was restored and seat coverings were replaced, as they had deteriorated over time. It wasn’t until later that they became objects for display and not until 1997, when the museum began a reupholstery campaign, that the original surfaces were tested. It was discovered that another layer of varnish existed under the gilding, suggesting that the gilding came after the original surface was completed. After a few years delay, it was decided to restore one sofa to its original 19th century appearance and the other to its appearance in the 20th century. The gilded sofa with the basket on the crest rail was cleaned and in-painted and in-gilded where necessary and went on exhibition in a new gallery while the other one went to conservation.

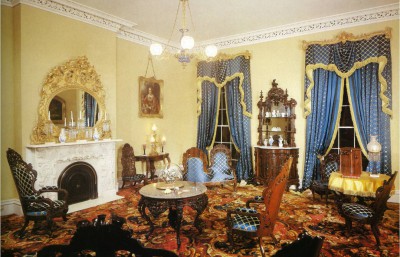

The other sofa was to be restored to its original mid 19th century appearance. Layers upon layers of gold leaf and paint had to be removed while preserving the original resin varnish on the wood beneath. Belter’s laminations could be seen as the sofa was restored and a new varnish was added to areas where the original varnish had been taken off during the conservation process. Specialist Jennifer A. Zemanek was commissioned by the museum to reupholster the sofa, using silk damask of a deep blue color picked by associate curator Susan J. Rawles to match the color and textile that would have been popular that the time the sofa was made.

Today, the sofas take turns being on view in the American galleries, showcasing the skills of Belter and the different periods of the sofas’ history.