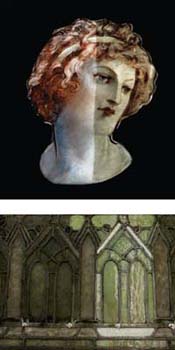

Image: Partially cleaned details of Christ Resurrection window

Image: Partially cleaned details of Christ Resurrection window

When the Christ Resurrection window is installed in the Cochrane Atrium of the museum’s new McGlothlin Wing, it will be the first time in more than 50 years that this ecclesiastical artwork, created by Tiffany Glass & Decorating Company, will be available for public view.

Until recently, this historic Tiffany window had been stored in a basement in Henrico County and, when located, was in various stages of deterioration.

The window was originally created for All Saints Episcopal Church around 1899, when the church was located at 308 West Franklin Street near the Jefferson Hotel in downtown Richmond. In 1958 the church moved westward to River Road to accommodate its growing and increasingly suburban congregation. According to newspaper reports from the time, church officials had intended to move all of the leaded-glass windows to the Henrico County location. But the architecture of the new building could not accommodate that plan, and the Christ Resurrection and The Blessing of the Children windows were left behind. Sometime around 1961, the downtown building was sold and razed to make way for a high-rise apartment building, and the two remaining Tiffany windows were removed and sent to be stored in the new church.

They remained there until the late 1990s. About that time, Scott Taylor of E.S. Taylor Studio, who specializes in the conservation of stained- and leaded-glass windows, was doing work on the Tiffany windows that are still part of the church. A vestry member informed him there might be more Tiffany windows in the church’s basement.

Taylor went downstairs to investigate. “There were three or four frames leaning against the wall,” he recalls. “When I started peeling them back, I realized that they were plated windows.”

Looking around, he also saw numerous pieces of glass lying on the floor. The plated windows and segments of glass from medallions led Taylor to surmise that the church might indeed have more Tiffany windows. Finding the Tiffany company signature on both of the windows provided the conclusive evidence.

That discovery proved to be fortuitous for the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. The church eventually decided to give Christ Resurrection to the museum as a gift, and VMFA purchased The Blessing of the Children through the Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund.

The two windows—each 12 feet tall—are made of leaded glass and are among an estimated 50 percent of Tiffany church windows that still exist, according to Barry Shifman, VMFA’s Sydney and Frances Lewis Family Curator – Decorative Arts from 1890 to the Present.

“These windows were designed by Frederick Wilson,” Shifman says, “probably the most gifted and longest-serving of the window designers at Tiffany Glass & Decorating Company.”

Before the windows could be installed in the renovated VMFA galleries, both needed extensive conservation work. The panels of the windows were still in their original frames but were deteriorating, Taylor says. They had been stored in a hostile environment for 50 years and exposed to the steamy weather that pervades the Richmond region every summer. Humidity and moisture in a closed environment pose the greatest threats to the extended life of stained- and leaded-glass windows.

But Taylor could not know the condition of the windows just by looking at them, as some of the panels had three to four layers of glass. Even if the exterior looked intact, interior parts of the window could still be compromised.

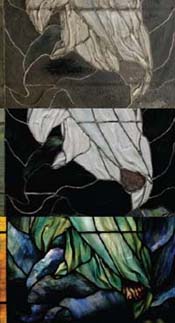

Image: Before and after details of the interior side of one of the larger panels of the Christ Resurrection window. The top and middle details show the foot of the Christ figure before conservation and photographed in reflected light. The bottom detail shows the same part of the window after conservation and photographed in transmitted light.

Once he had a record of how the windows were constructed, he was able to disassemble them for treatment. That’s when he knew the extent of the problem. In just three of the panels he found approximately 100 pieces of broken glass as well as a number of other pieces that were already undergoing chemical devitrification—a process whereby the glass begins to disintegrate and revert back to its original constituents. “Once that starts, there’s no way to reverse it,” Taylor says. He was able to treat most of the affected glass, keeping it stabilized for the present time. Where there was total or partial loss of a particular piece of glass, he had to replace it. A suitable match was located from a modern-day glass company and was used to replace four pieces in the entire window.

Taylor and his associate Mary Lu Winger then took the treated and new pieces of glass and put them back in place, using the rubbings and photos of the windows to guide them on the design. They used deionized water and neutral pH cleaners to remove accumulated dirt and grime, which in turn considerably enhances the illumination of the windows.

All glass in the windows is held in place by lead. Original pieces of lead were reused where possible, but some of the lead was corroded and had to be replaced. In addition to its structural function, the lead in Tiffany windows is also part of the design. It has to be molded to conform to the glass to which it is attached. For instance, Taylor says, lead holding the drapery glass undulates to conform to the folds in the glass.

Conserving these two windows is taking months to finish, which is why there is not a photograph of either window to accompany this article. The museum has not yet determined where The Blessing of the Children will be located. However, when the museum opens in May, the newly conserved Christ Resurrection will be on display in the Cochrane Lounge, part of the American Galleries.

“It’s crucial to add examples of Tiffany’s most important contribution to American art—ecclesiastical leaded-glass windows—to our otherwise extensive collection of Tiffany objects,” Shifman says. “VMFA is pleased to collaborate with All Saints Episcopal Church in this effort to preserve a glorious part of American history.”