This post is one in a series highlighting the special exhibition Nightfall: Prints of the Dark Hours, which explores evocative artistic images of night, called nocturnes. The exhibition is on view through March 22, 2016, in the VMFA Works on Paper Focus Gallery. Admission is free.

Rockwell Kent’s Starry Night: What to Do at Night?

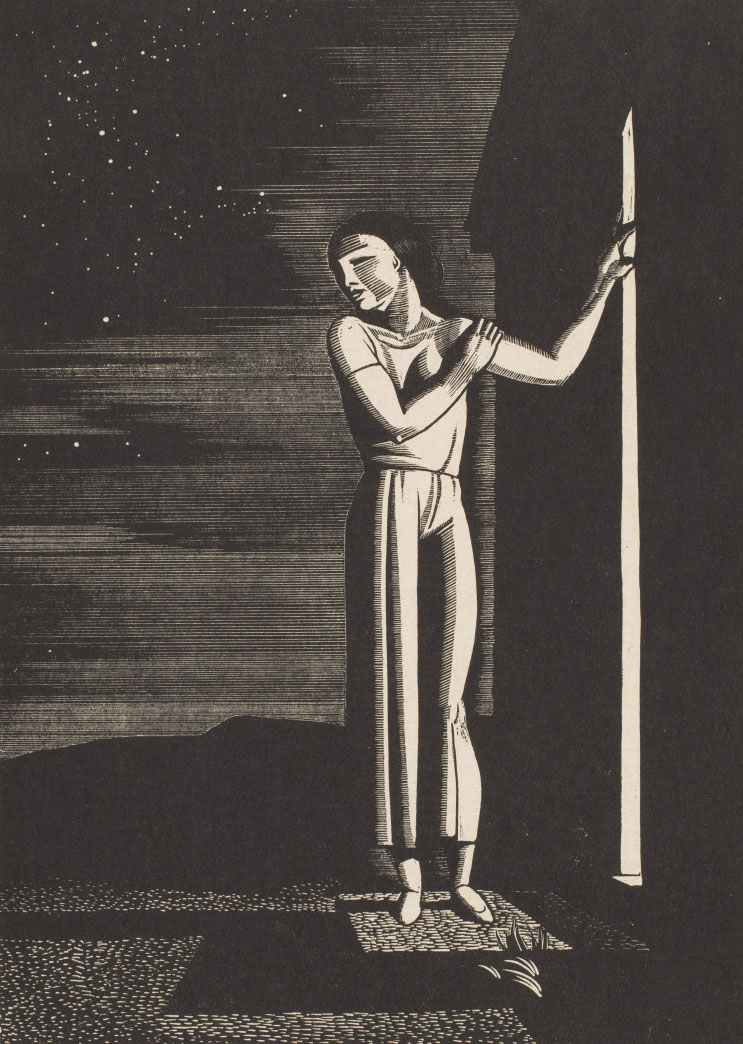

In Starry Night (1933), American artist, writer, and philosopher Rockwell Kent (1882–1971) introduces the central question explored by, and posed through, the exhibition: what is night to a human being? A sole figure stands on the front step of a house with one hand holding onto the door frame, positioned between the vast outside world covered by a starlit sky and the inside of an abrasively and artificially lit home. Her posture suggests that she is not comfortable outside, yet she also physically recoils from the brightness indoors. Kent’s nocturne invites the viewer to consider the same dilemma that its subject faces: trying to decide where one really belongs, and why.

Regarding man’s attempts to come to terms with nature, Kent believed:

Rockwell Kent (American, 1882–1971), Starry Night, 1933, wood engraving on maple, sheet: 10 × 7 9/16 in. plate: 7 × 5 in., Promised Gift of Frank Raysor, FR.7004

In that Beginning there was energy in chaos. And God breathed order into chaos, gave it law, direction. . . . Then living things achieved the power to perceive and feel and to desire; all their perceptions were essential to the continuity of life. So came discrimination, prompted by the sense of pain or pleasure. And then came consciousness, and man was born. Man looked about him and perceived the order of the universe . . . the accustomed movement of all living things. He perceived the movement and proportions of mankind. . . . He everywhere perceived an ordered universe with law prevailing; and he was pleased and comforted by the entire aspect of his world, for he was of it, tuned by his nature to its harmonies and rhythms—so sensitively tuned that violation of them hurt . . . not quite content to be an incident in an impartial world, or overwhelmed by the world’s immensity, man strove to narrow it toward the limitations of his mind.

—Kent, “Of Aesthetics” in Rockwellkentiana:Few Words and Many Pictures (1933)

Kent viewed natural law—including the passage of day to night—as a divinely ordained set of rules that people later sought to narrow to their own preferences. This could explain why the seemingly endless landscape that surrounds the figure in Starry Night appears serene under a sky sprinkled with twinkling stars, while the light emanating from the house seems harshly in contradiction to nature.

Although moving in a spiritual sense, Starry Night presents only one perspective of an event all people experience: Kent’s vision that nighttime ought to be left alone to be nighttime, unencumbered by man’s preferences and efforts to overcome darkness. Imagine if one worked at night or lived in a place that posed more perceptible danger than the pastoral dream in which the print’s ambivalent protagonist appears to live. Nightfall: Prints of the Dark Hours presents this woodcut among several nocturnes by American and European artists that depict piety, loneliness, celebration, and other moods and experiences occurring at night throughout centuries. Though the exhibition highlights nighttime as a universal theme, it also emphasizes the subjective nature of one’s experience of something as seemingly objective as darkness.

Bailey Goldsborough

Curatorial Intern,

VMFA Department of European Art