This post is one in a series highlighting the special exhibition Nightfall: Prints of the Dark Hours, which explores evocative artistic images of night, called nocturnes. The exhibition is on view through March 22, 2016, in the VMFA Works on Paper Focus Gallery. Admission is free.

Nighttime acts, for many, as a sphere in which to muse on things invisible: thoughts, feelings, and memories may take on lives of their own in the hours of the day unencumbered by the burdens of seeing or knowing. In religious processions, for example, the metaphysical takes on physical form. Just as such ceremonies involve more than what meets the eye, visual depictions of them are more than historical documents because of choices made by the artist, such as lighting, scale, and tone. Nightfall features two views of Christian religious ceremonies taking place at night that reflect such artistic interpretations: Gene Kloss’s Christmas Eve—Taos Pueblo (1996) and Robin Tanner’s Christmas (1929).

Christmas Eve—Taos Pueblo by California native Gene Kloss (1903–1996) exemplifies sincere observation of a religious ceremony filtered through the lens of prefabricated cultural assumptions. This image, with its dramatic lighting and monumentalizing pyramidal composition, evokes notions of the supernatural while still operating within the realm of human possibility. Kloss herself seems to have been taken by the way of life of the native people of Taos Pueblo, New Mexico. In fact, after spending their honeymoon there, Kloss and her husband decided to move to Taos, where she worked en plein air on a portable printing press. Kloss explains her fascination with the people of Taos:

Gene Kloss (American, 1903–1996), Christmas Eve–Taos Pueblo, 1945, drypoint, aquatint, 14 3/8 X 17 7/16 in. Purchased as a gift of Frank Raysor in gratitude for VMFA’s Member Travel Program, 2014.228

Later on Good Friday we saw the fires near us, and they sent one of their number down by our little house with a ratchet – the devil chaser that went clackety-clack around – to admonish us to stay put and a group came up the road with a torch. . . Their voices grew louder and then they went into…the little chapel. . . The Indian is very virile. We used to hear them singing on horseback as they passed here.[i]

The mystical imagery and usage of words like “virile” imply a certain degree of exoticism in Kloss’s view of the Taos people. This belief that the native people are somehow more connected to the natural/supernatural could explain some of the visual choices made by Kloss in this print. The vivid contrasts between light and dark, the equation of the clay pueblo houses to the forms of the mountains behind them, and the seemingly divine moonlight placed at the zenith all evoke the visual experience that so mesmerized Kloss.

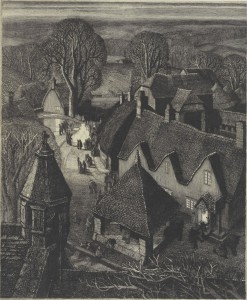

Robin Tanner (English, 1904–1988), Christmas, 1929, etching, 11 7/8 x 17 3/4 in. Promised Gift of Frank Raysor, L.139.2010.62

English etcher Robin Tanner (1904–1988) worked within the stylistic tradition of neo-romanticism, a movement that arose in reaction to the rampant urbanization of England. People in England, feeling alienated from the city and all its baggage, began to turn to what they saw as the untainted countryside as a way to affirm their own national identity. With this in mind, Tanner’s pastoral Christmas becomes an image of more than just people in a town on a given day. This scene of a rural English town at dusk, full with its thatched-roof houses, towering and bare-limbed trees, still pond, rolling hills in the distance, and people throughout gathered peacefully around lanterns or joining in games as the bell tolls is nice for what it is but more telling in what it is not. If urbanization meant danger, overcrowding, and general dismay, this vision of people of the countryside joining happily together in observance of a Christian holiday offers a dream that Tanner and his fellow neo-romanticists ostensibly found appealing. This print, made right on the cusp of the Great Slump (the British nomenclature for the Great Depression) is just as much a yearning for a certain cultural reality as it is a depiction of an existing one. Tanner said as much himself:

Of course I am an idealist. My etched world is an ideal world, a world of pastoral beauty that could still be ours if we did but desire it passionately enough, instead of poisoning it.

In art making, it is inevitable that artists would unload something of their own cultural education into the work they produce, be it a religious image, a portrait, a landscape, a color-field painting, an abstract sculpture, or even a building. In a practice so based on deliberate choices as printmaking, the natural tendency toward cultural projection becomes very clear. In the two scenes of Christian religious processions discussed here, the differences in the images seem just as resultant of the subjects’ actual differences as they are of the different ways in which the artists prefer to view the subjects’ cultures.

Bailey Goldsborough

Curatorial Intern,

VMFA Department of European Art

[i] Gene Kloss, Interview by Sylvia Loomis, “Oral history interview with Gene Kloss,” Taos, New Mexico, June 11, 1964