This post is one in a series highlighting the special exhibition Nightfall: Prints of the Dark Hours, which explores evocative artistic images of night, called nocturnes. The exhibition is on view through March 22, 2016, in the VMFA Works on Paper Focus Gallery. Admission is free.

Nightfall includes two scenes of divine apparitions: William Strang’s Manoah’s Offering (1884) and Rembrandt van Rijn’s Angel Appearing to the Shepherds (1634). The penetration of darkness by light as employed in the Bible often evokes some instance of the divine breaking through to the human realm. This use of light and dark produces a clear contrast between the Christian ideas of the omniscience of God and the lowliness and humility of those bound to the earthly realm.

Scottish painter and printmaker William Strang (1859–1921) is known for psychologically intense etchings. Strang trained under realist painter and engraver Alphonse Legros at London’s Slade School of Art. Although he gained recognition for his painted portraits and landscapes rendered in a more naturalistic style, Strang also produced some religious works like Manoah’s Offering.

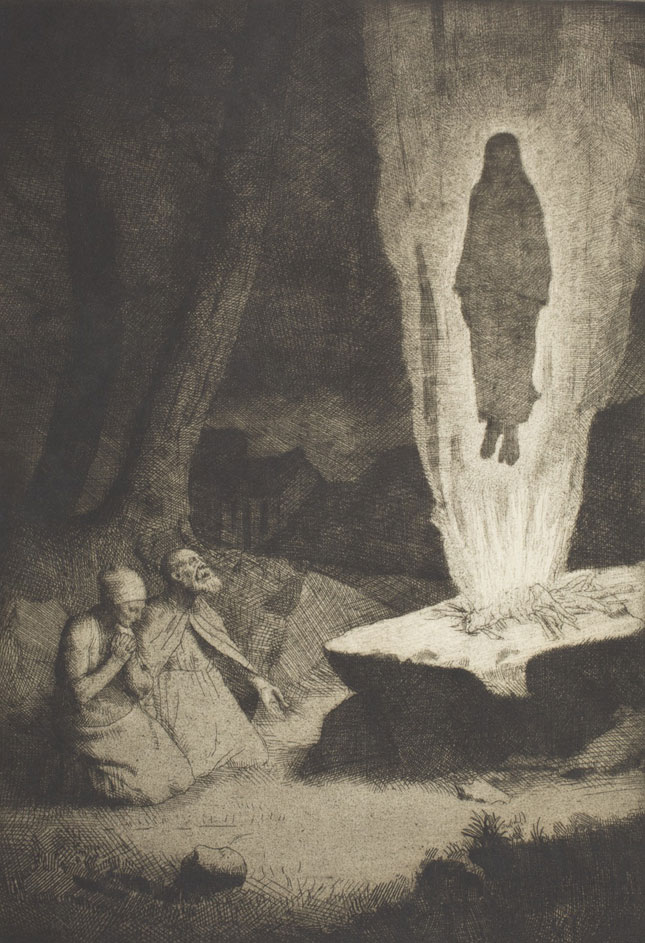

William Strang (Scottish, 1859–1921), Manoah’s Offering, 1884, etching, mezzotint, sheet: 11 5/8 x 7 7/8 in. Promised Gift of Frank Raysor

Derived from the Old Testament Book of Judges (Chapter 13), this scene depicts the moment just after an angel appeared to Manoah and his wife to announce that they will in fact be able to have a baby. The angel had spelled out to Manoah’s wife certain dietary restrictions, telling her to “drink no wine or other fermented drink and do not eat anything unclean”—as her miracle child is to be a Nazirite (or servant) of God “from the womb until the day of his death” (Judges 13:7). Their son, Samson, would grow up to become a legendary long-haired, divinely inspired strongman.

Manoah, understandably humbled and terrified at seeing an embodiment of his God right before his eyes, offered a goat as sacrifice. However, the angel said it should instead be burned and offered to God directly. As the angel ascends in “the flame of the altar,” Manoah looks up in fear and confusion and his wife bows her head and clasps her hands in reverence. Later, Manoah voices his fear to his wife that they are bound to die because they saw God. His wife, however, believes that if God had wanted to kill them, He would not have gone through the trouble of sending an angel to make the annunciation, given advice, or accepted the offering. Strang uses the light of the fire to create a contrast between the pastoral world in which Manoah and his wife live (see trees, modest houses in the background) and the divine spectacle taking place.

Rembrandt Van Rijn (Dutch, 1606–1669), The Angel Appearing to the Shepherds, 1634, etching, drypoint, engraving (burin), sheet: 10 1/4 x 8 3/4 in. Alice and Lewis Nelson Fund, Frank Raysor Fund, and Kathleen Boone Samuels Memorial Fund

Dutch painter and etcher Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) presented a biblical apparition in a much more grandiose manner some two hundred years earlier in Angel Appearing to the Shepherds. Right after Mary gives birth to Jesus, an angel appears to the shepherds of a neighboring town while on their night shift to tell them that the Messiah was lying in a manger the next town over. Rembrandt’s depiction of “the glory of the Lord” (Luke 2:9) differs from Strang in its theatricality. Much the opposite of Strang’s almost-eerie lone figure, modestly clad and calmly ascending in a flame, Rembrandt’s winged angel holds his hands out like a great orator while perched atop a cloud backed by a huge shining orb wildly spewing cherubs out into the night sky. At ground level, shepherds and animals alike frenetically run around and trip over each other in response in what is ostensibly an otherwise calm woodland setting. If Strang’s apparition prompted Manoah and his wife to try to process the event privately and internally, Rembrandt’s angel spectacle elicits from its audience a very outwardly frantic reaction.

These two approaches to dealing with fairly similar biblical phenomena conjure up two different conceptions of God, specifically in relation to humans. Strang’s angel evokes a relatively sober, personal relationship between his subjects and their god, as He came to their home, talked with them, and accepted their offering. On the other hand, Rembrandt seems more interested in emphasizing the grandness of God in contrast with the lowly modesty of humans, as the angel stirs up the men and their flock in presenting his news. These two prints show the degree to which people’s ideas of the divine can differ, even when reading from the same book.

Bailey Goldsborough

Curatorial Intern,

VMFA Department of European Art