Audio tour best experienced with headphones

Tour Stop: 01

Curator’s Introduction

This is the first exhibition ever to explore the connection between Johns and Munch, artists born nearly seventy years apart on different continents. It offers an in-depth look at when and how the Norwegian expressionist art of Munch entered into the American modernist art of Johns.

The connection between these two artists may seem surprising given the great difference in their approaches. While Munch embraced feelings and personal experience as sources for his art, Johns used pre-existing images that belonged to everyone–letters, numbers, and the American flag. Despite these differences, Munch’s art helped open Johns to new content and a broadened range of expression.

Over the course of the exhibition, you’ll gain insight into Johns’s creative process and how he drew inspiration from Munch’s work through quoting, transforming, and repurposing. This audio guide has 20 stops and works of art included on the guide are marked with a headset icon on the label.

We also invite you to participate in an interactive space at the end of the exhibition called the Artist’s Studio, where you can continue to explore motifs and themes in the work of Johns and Munch.

This exhibition was organized by VMFA in partnership with the Munch Museum in Oslo, Norway and is presented at VMFA by Altria Group.

Educational programming for Jasper Johns and Edvard Munch: Love, Loss, and the Cycle of Life is generously supported by the Robert Lehman Foundation.

We hope you enjoy the exhibition and thank you for visiting VMFA!

Close

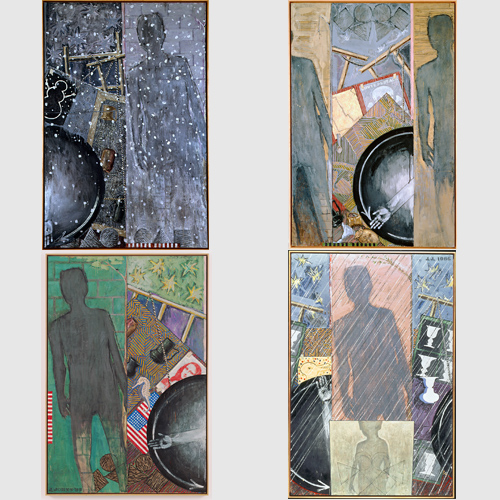

Four Panels From Untitled 1972, 1974, Jasper Johns (American, born 1930), lithographs with embossing. Courtesy of Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles

Tour Stop: 02

Johns, Four Panels from Untitled 1972 (1974)

Jasper Johns

(American, born 1930)

Four Panels From Untitled 1972

1974

Lithographs with embossing

Courtesy of Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles

In 1974, when this series of lithographs was made, Johns had embarked on a ten-year period in which crosshatching would be the exclusive subject of his paintings. Since the 1950s, he had been working with found objects in his art, depicting impersonal things like flags and targets, in his own words: “something that wouldn’t have to carry my nature as part of its message.”

One day, while driving towards the Hamptons for the weekend, he spotted a car, conspicuously covered in marks resembling crosshatching, coming in the opposite direction. The car appeared in a glimpse and was gone. Johns had stumbled upon a new, found object. He later explained his initial attraction to crosshatching:

“It had all the qualities that interest me: literalness, repetitiveness, an obsessive quality, order with dumbness, and the possibility of a complete lack of meaning.”

Yet, for all its apparent lack of meaning, the motif also carries a reference to a basic means in the graphic arts, as crosshatching has been used since the Middle Ages to create illusions of space and light and shade. As Johns repeatedly worked with crosshatching, gradually making the motif more his own than taken, he was mining a fundamental unit in his existing artistic vocabulary, elaborating and magnifying something intimately familiar.

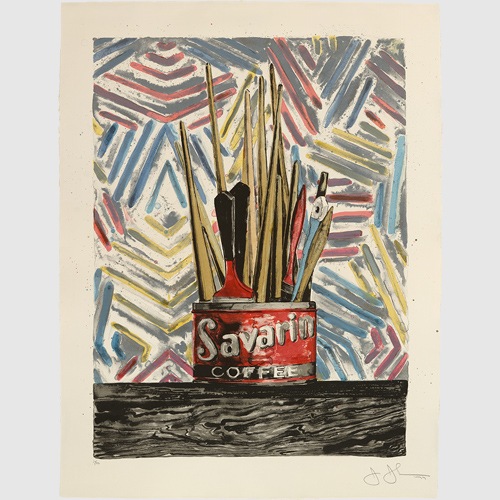

Savarin, 1977, Jasper Johns (American, born 1930), lithograph. Courtesy Universal Limited Art Editions

Tour Stop: 03

Johns, Savarin (1977)

Jasper Johns

(American, born 1930)

Savarin, 1977

Lithograph

Courtesy Universal Limited Art Editions

The many versions of the Savarin motif on display in this exhibition exemplify how Johns would gradually develop motifs over long periods of time. Together they form a series of images undergoing incremental evolution, frequently taking new and unexpected turns. The first piece in this series, from 1960, was a painted bronze sculpture of the artist’s brushes resting upside down in an empty tin of Savarin coffee. This bronze combined the impersonal, found objects that intrigued Johns with something profoundly intimate: the tools he used to create art.

During the `60’s, Johns explored the motif in etchings and lithographs. Then, in 1977, he printed the Savarin tin against a background of colorful crosshatching for the poster for that year’s retrospective at The Whitney Museum in New York. Looking at the poster, we glimpse wood grain under the exhibition text, drawn, rather unusually for Johns, by hand. In the image we’re looking at now, Johns has removed the text and the wood grain has fully surfaced. During this period, Johns was deeply involved in exploring various printing techniques, and he was particularly interested in Munch’s woodcuts and lithographs.

Whether Johns is deliberately referring to Munch’s woodcuts in this image is uncertain, however by introducing the hand-drawn space below the Savarin-tin he had created a separate, autonomous field in the image. That the artist’s brushes resting upside down in the coffee tin was a symbolic self-portrait was to become more apparent in later versions of the image. In the field below the tin, which thus far contains the illusion of wood grain, an outright reference to Munch was about to surface.

The Kiss IV, 1902, Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863–1944), woodcut. Munch Museum

Tour Stop: 04

Munch, Kiss IV (1897–1902)

Edvard Munch

(Norwegian, 1863–1944)

The Kiss IV

1902

Woodcut

Munch Museum

Munch created his first woodcuts in 1896. In this series, The Kiss, two figures are inscribed in a single form against a background of distinct wood grain. Munch first explored this motif in a painting several years earlier, in which the couple are merged together to form a solid, unified form. In this woodcut, Munch has emphasized the oneness of the two figures by cutting them out in a single piece of wood, as though they were a piece of a jigsaw puzzle. The two are superimposed on the imprint of a heavily grained plate of wood, and the grain is visible through the couple, making them appear partially transparent. Munch’s distinct use of wood grain in images like this one has been an important precedent for Johns’s prints.

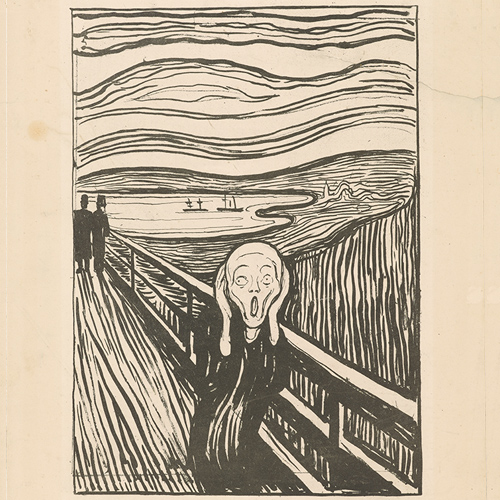

The Scream, 1895; signed 1896, Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863–1944), lithograph. Munch Museum

Tour Stop: 05

Munch, The Scream (1895)

Edvard Munch

(Norwegian, 1863–1944)

The Scream

1895; signed 1896

Lithograph

Munch Museum

This printed version of The Scream is a lithograph, yet it has been mistaken for a woodcut since the outset. Although the image was made a year prior to Munch’s first experiments with woodcuts, its broad and organic black lines resemble those produced in woodcut printing. In place of the stark color contrasts of the painting, Munch has used strong, undulating lines to convey the anguished experience of sensing “a great infinite scream in nature.” As we have seen in the Savarin motif, Johns has also experimented with applying feigned wood effects in lithographs. Commenting on the intermingling of techniques and styles in Munch’s Kissand The Scream, Johns says:

“And you don’t really know what the connection between the pattern in The Scream and the wood grain in The Kiss is, you don’t know which comes first in his mind.”

Does the Scream lithograph resemble a woodcut because Munch had studied wood grain, or did he become fascinated by wood because it contained the kinds of shapes he used in his works?

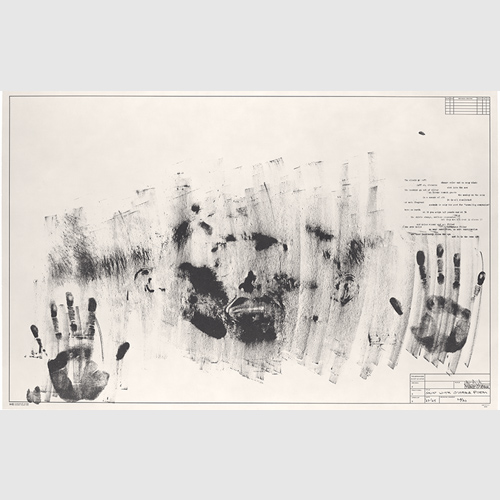

Skin with O’Hara Poem, 1965, Jasper Johns (American, born 1930), lithograph. Ryobi Foundation

Tour Stop: 06

Johns, Skin with O’Hara Poem (1965)

Jasper Johns

(American, born 1930)

Skin with O’Hara Poem

1965

Lithograph

Ryobi Foundation

This lithograph from 1965 is based on a series of experimental drawings that the artist had made three years earlier. These works had heralded the use of handprints in Johns’s art. To make the image, Johns smeared his hands and face with transparent oil, and rolled his face across the paper like a cylinder seal. The image then appeared as Johns applied charcoal to the surface. As the title suggests, the image is a physical imprint of Johns’s body on a flat piece of paper. The volume of the head is stuck on a two-dimensional plane that the artist appears to be desperately trying to escape from in a struggle between flatness and space. Above and to the right, Johns has included a transcription of Frank O’Hara’s poem The Clouds Go Soft.

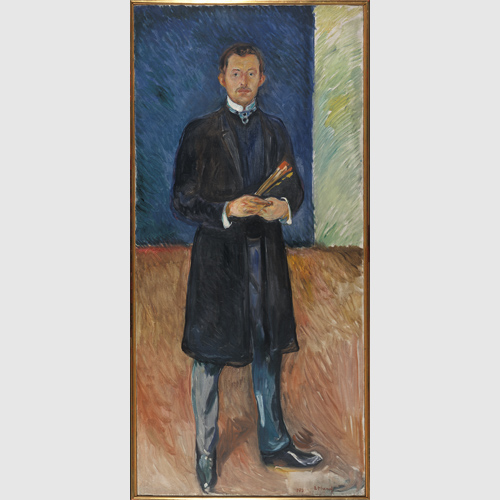

Self-portrait with Brushes, 1904, Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863–1944), oil on canvas. Munch Museum

Tour Stop: 07

Munch, Self-Portrait with Brushes (1904)

Edvard Munch

(Norwegian, 1863–1944)

Self-portrait with Brushes

1904

Oil on canvas

Munch Museum

In Self-Portrait with Brushes, Munch directly engages with a long tradition of artists, from Rembrandt to Van Gogh and Frida Kahlo, who portray themselves with brushes and palettes to emphasize their identities as painters. Munch alludes to this pictorial convention in several of his self-portrayals, and in this full figure portrait from 1904 the brushes alone indicate that the debonair sitter is also a painter. In a photograph, also from 1904, Munch poses in a similar fashion, brushes in hand.

The self-portrait we’re looking at, along with Self-Portrait with Skeleton Arm, connects to Johns’s depictions of the Savarin tin. By displaying the tools of his trade against a backdrop of crosshatching, Johns implicitly points to something individual and personal; himself and his artistic practice. We may therefore interpret the image of the brushes in the coffee tin as a substitute for the artist. In this way, the image becomes an oblique self-portrait. Playing on personal subject matter in this way differs from Johns’s earlier work, in which the creative powers of the artist were subordinate to the motif, often using a found or pre-existing object without any apparent connection to the artist himself.

Close

Savarin, 1977–81, Jasper Johns (American, born 1930), lithograph. Private Collection

Tour Stop: 08

Johns, Savarin (1977–81)

Jasper Johns

(American, born 1930)

Savarin

1977–81

Lithograph

Private Collection

Sometime in late 1978 or in early 1979, Johns visited the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, to see the exhibition Edvard Munch: Symbols & Images. The occasion provided Johns with the opportunity to closely examine Munch’s prints, drawings, and paintings. Johns had been aware of Munch as early as 1950, when he saw works by the Norwegian artist displayed at The Museum of Modern Art in New York. It would seem reasonable to assume that the Savarin prints featuring skeleton arms were conceived after Johns’s visit to the exhibition at The National Gallery, but they were actually made in May 1978, several months prior to his trip to Washington.

Johns worked with Savarin lithographs in two different periods between 1977 and 1981. As we have seen earlier in this exhibition, the first print, made in 1977, was the poster for the retrospective at The Whitney Museum. In 1981 he added the soft, grey hues to the image, as well as some of the dark sections of the crosshatching and, not least, the red arm and the stenciled letters ‘E M’, lining the bottom of the image. Appearing here, it is in keeping with Johns’s practice of printing his own arm, while the letters explicitly reference Munch’s initials, suggesting how the entire image recalls Self-Portrait with Skeleton Arm from 1895.

The version of the Savarin print we’re looking at now exemplifies how chance and new discoveries have shaped the evolution of the motif. The space at the bottom of the image had in earlier states of the print contained either a text or imitation wood grain, before becoming in this version a concrete reference to Munch and his self-portrait. By referencing Munch and his symbolist meditation on the artistic process, the image also becomes a self-portrait of Johns once removed, commenting on the artist’s own creative practice.

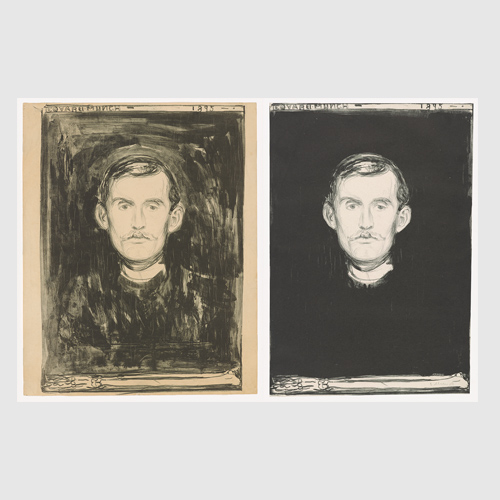

Self-portrait (with Skeleton Arm), 1895 (all three states), Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863–1944), lithograph. Munch Museum

Tour Stop: 09

Munch, Self-Portrait with Skeleton Arm

(1895, all three states)

Edvard Munch

(Norwegian, 1863–1944)

Self-portrait (with Skeleton Arm)

1895 (all three states)

Lithograph

Munch Museum

This lithograph is Munch’s first printed self-portrait, executed in 1895 in three different states. A lithograph is a print made by drawing on a slab of limestone with greasy ink. The stone is then moistened and ink is applied, sticking only to the untreated areas of the stone, as the greasy ink repels the water. Printing paper is then applied to the stone and rolled through a press, leaving a mirrored imprint of the drawing on the paper.

The first version of the self-portrait has a loosely sketched background and the head appears attached to the upper body. The skeleton arm replaces the hand of the artist, its placement at the bottom of the image referencing a conventional formula for self-portraits popular since the renaissance, used by artists like Rembrandt and Dürer. In the final state of the print, Munch has eliminated all detail, leaving only the head levitating against a dark void.

The most popular version of the lithograph, however, is the second state, made in between the two other impressions. Here we find a stark contrast between light and shade. The head and the arm appear in greater isolation than in the first state, the skeleton arm resembling a holy relic, detached from the body. The artist’s signature appears along the lower edge of the skeleton arm, and along the upper border of the image, evoking a tombstone, we find Munch’s name and the year of the portrait’s creation.

Thus, the image summons notions of death and decay. Munch has portrayed himself without a body, reduced to his face and hand, the traditional attributes for the spiritual and creative faculties of the artist. In this way, Munch alludes to what is known in art history as memento-mori, meaning ‘remember that you must die’. Munch meditated on death throughout his artistic career, and in 1895, when this image was made, he had recently experienced the loss of his younger brother Andreas.

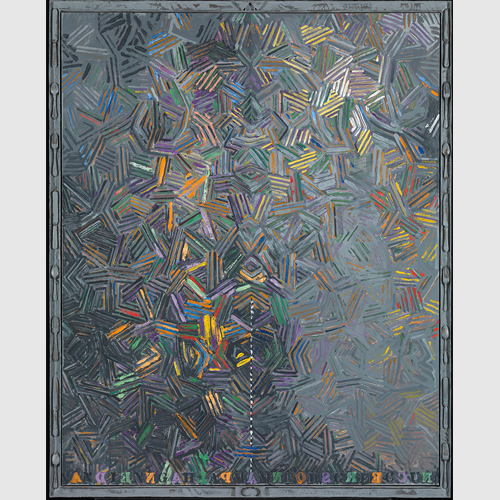

Dancers on a Plane, 1980–81, Jasper Johns (American, born 1930), oil on canvas and bronze frame. Tate London: Purchased 1981

Tour Stop: 10

Johns, Dancers on a Plane (1980–81)

Jasper Johns

(American, born 1930)

Dancers on a Plane

1980–81

Oil on canvas and bronze frame

Tate London: Purchased 1981

This painting is above all a tribute to Johns’s friend and collaborator Merce Cunningham, whose name appears at the bottom in letters alternating with the work’s title. Cunningham has since the 1950s been considered among the most significant choreographers in modern dance, and Johns worked for thirteen years as artistic advisor to the Cunningham Dance Company.

The image and its title bring to mind Munch’s engagement with the subject of dance in a range of images. In several such works, like The Dance of Death and Death and the Maiden, the themes of death and eroticism are connected to dance. Johns had a book on tantric art, and was intrigued by Samvara, the Buddhist deity with multiple arms who is portrayed in images alongside his beloved consort in an ecstatic dance of procreation and self-abandonment. This painting carries two highly stylized tantric motifs with sexual connotations. The oval shape on the lower edge represents testicles, while at the top center a vertical shaft between two triangles represents a phallus and vagina.

Johns’s use of marginal notes and sketches had a casual appearance in the Cicada drawing, but it assumes a more studied and deliberate role in Dancers on a Plane. The frame includes casts of spoons, knives, and forks running up and down the sides. Consumption and digestion are thus metaphorically linked to the larger themes of love and mortality. The cast cutlery lining the frame also recalls Munch’s use of marginalia surrounding his images. A version of Madonna is encircled with sperms, and a fetus-like figure appears in the corner of the image. The figure also recalls a cranium, or an aborted fetus, evoking the themes of reproduction, life, and death that appear in Johns’s painting.

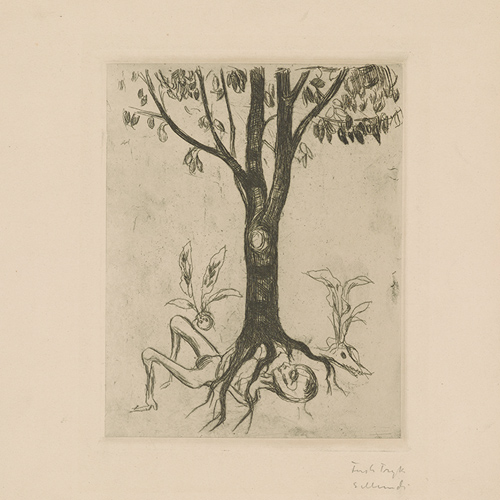

Life and Death, 1902?, Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863–1944), etching. Munch Museum

Tour Stop: 11

Munch, Life and Death (1902)

Edvard Munch

(Norwegian, 1863–1944)

Life and Death

1902?

Etching

Munch Museum

The cycles of life and nature were subjects that Munch returned to repeatedly throughout his artistic career. As we have seen earlier in the exhibition, he explored notions of how creation and destruction and life and death are linked together in a perpetual cycle in the Madonna prints and paintings. In other images, like Metabolism and Life and Death, the cyclical process of nature mirrors that of man. Munch’s motifs about such cycles of life are generally composed in a similar fashion with two horizontal bands, the lower depicting death and decay, the upper light and life. From decaying matter, new life rises, as in this etching from 1902, entitled Life and Death. Here, a tree rises from human remains, its roots drawing nutrition from the decomposing body. Two plants sprouting up from skull like shapes flank the tree, one from the cranium of a man on the left, the other from that of an animal to the right. In a collection of texts called The Tree of Knowledge, Munch writes:

“Up from my rotting carcass flowers shall spring up – and I shall be in them – Eternity.”

Dance of Life, 1925, Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863–1944), oil on canvas. Munch Museum

Tour Stop: 12

Munch, The Dance of Life (1925)

Edvard Munch

(Norwegian, 1863–1944)

Dance of Life

1925

Oil on canvas

Munch Museum

By exhibiting his paintings together in a series of images, Munch attempted to render the life of modern man as a collective whole. This cycle of paintings later became known as ‘The Frieze of Life.’ In 1918, he described the idea in these words: “The Frieze is intended as a number of decorative pictures, which together would represent an image of life. The sinuous shoreline weaves through them all, beyond it is the ocean, which is in constant motion, and beneath the treetops multifarious life unfolds with all of its joys and sorrows.

The Dance of Life, here in a painting from 1925, is a motif recurring in several versions and is regarded as the core image in ‘The Frieze of Life’. In it, the rituals of life and love are enacted as a dance with the shoreline as the stage. The three women in the foreground are archetypes. The innocent and expectant maid is clad in white, reaching for a flower. The dark-eyed temptress, dressed in red, is in the whirlpool of an ecstatic dance with her spellbound companion, while the aging woman, dressed in black in the twilight of life, is posed with her hands folded in her lap and her head bowed.

‘The Frieze of Life’ was exhibited under a variety of titles. In Berlin, in 1893, it was called “Study for a series: Love”. In 1914 in Oslo, called Christiania at the time, it was dubbed “Frieze. Motifs from the Life of the Modern Soul,” before being shown again in Oslo in 1918 under its final name, “The Frieze of Life”. These related exhibitions were far from homogenous, and only a handful of motifs remained in the series throughout its evolution: The Kiss, Melancholy, and The Scream. To Munch, The Dance of Life summed up the central theme in ‘The Frieze of Life:’ love’s flowering, the dance of life, the summit of love, its gradual decay, and, finally, death.

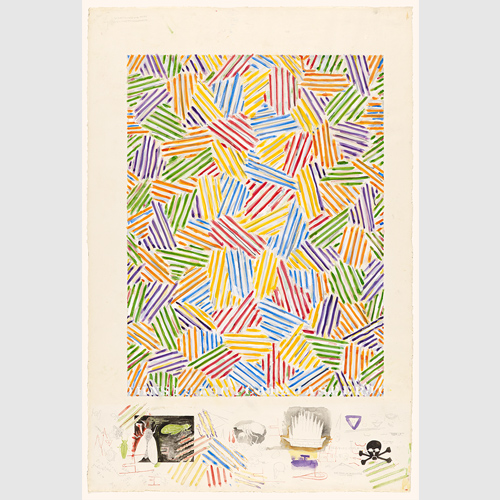

Cicada, 1979, watercolor, crayon, and pencil on paper. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund

Tour Stop: 13

Johns, Cicada (1979)

Jasper Johns

(American, born 1930)

Cicada

1979

Watercolor, crayon, and pencil on paper

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund

This watercolor was made a couple of months prior to the painting of the same title, but differs from the latter in that Johns has included notes and sketches about sex, death and regeneration along the lower boarder of the image. These include cicadas, skulls, stylized symbols for sexual intercourse and genitalia, and a lamp-like form with flames representing a cremation pyre. Below it and to the right, appears the text: “Pope prays at Auschwitz: ‘Only Peace’,” a headline Johns had come upon in The New York Times about Pope John Paul II’s visit to the death camp in 1979. These notations and sketches are of the sort that Johns normally had reserved for his private notebooks. The work’s title, Cicada, is also stenciled onto the image, referring to the insect and its life cycle.

The composition evolves centrifugally from the center, with hatches in the primary colors red, yellow, and blue gradually giving way to the secondary colors green, purple, and orange. This dynamic movement of color is a reference to the cicada shedding its husk, one form replacing another.

The cicada lives buried under ground for up to seventeen years, feeding off of moisture from plant roots. It then surfaces to discard its exoskeleton and emerges as a winged adult for a brief mating season before dying. The life cycle of the cicada thus becomes a symbol of metamorphosis and change, and of the inseparability of life and death, a theme also recurrent in several of Munch’s motifs, like Madonna and Metabolism.

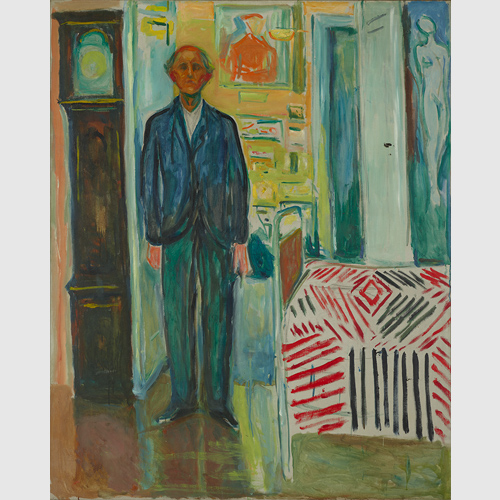

Self-Portrait between the Clock and the Bed, 1940–42, Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863–1944), oil on canvas. Munch Museum

Tour Stop: 14

Munch, Self-Portrait between the Clock and the Bed (1940–42)

Edvard Munch

(Norwegian, 1863–1944)

Self-Portrait between the Clock and the Bed

1940–42

Oil on canvas

Munch Museum

In this self-portrait from the early `40’s, the nearly 80 year-old Munch has portrayed himself at home in his house Ekely, outside of Oslo. Towards the end of his life, he had withdrawn to only a handful of rooms in the large, yellow house in which he had lived and worked since 1916. These rooms form the backdrop for Munch’s self-portrait, in which he is posing between his bed and the grandfather clock. The narrow bed juts into the room from the side, resembling a hospital bed and covered in a thin bedspread with a distinctive pattern in red and black. Comparison with the actual bedspread, on display here, shows that Munch took liberties in depicting it. Red is exchanged for black, and diagonals are swapped for verticals.

Self-Portrait between the Clock and the Bed is saturated with references to death. The dial on the clock shows no hands, a symbol of the passage of time, or perhaps its termination. It appears as if we are looking into a timeless vacuum, the bed evoking the finality of death. Lodged between the clock and the bed, the artist has portrayed himself on the threshold of death, prepared to walk his final steps. Behind him, the door opens up to a warm and yellow room in which the paintings on the wall hang as mementos of the artist’s lifework.

Between the Clock and the Bed, 1981, Jasper Johns (American, born 1930), oil on canvas. Collection of the artist

Tour Stop: 15

Johns, Between the Clock and the Bed (1981)

Jasper Johns

(American, born 1930)

Between the Clock and the Bed

1981

Oil on canvas

Collection of the artist

Johns’s three monumental paintings, called Between the Clock and the Bed, constitute perhaps his most direct reference to Munch’s impact on his art. The paintings were executed between 1981 and `83, and form the grand finale of Johns’s enduring work with crosshatching. Each painting consists of three panels with each their own set of rules and rhythms, the crosshatching forming a continuity that connects them together. As a whole, the three paintings constitute a complex exploration of the affinities and dissimilarities of unique and repeated patterns. This painting, which Johns started working on in 1982 and finished the next year, is the third and last of the series.

Why has Johns named these abstract paintings after Munch’s self-portrait? The title seems to imbue them with a specific meaning, or at least summon notions of something figurative. Johns had seen Munch’s painting for the first time at the New York exhibition in 1950 and again, in Washington, in 1978. John Ravenal, curator of Johns + Munch, explains:

“Surrounded by examples of his work, positioned between symbols of mortality, Munch offers an image of the artist on the cusp of a great transition. It is not surprising that Johns—already engaged with Munch’s work for several years and on the cusp of his own great transition—found in this complex painting a way to signal the end of an entire phase of his work and cross a threshold into new territory – figuration.”

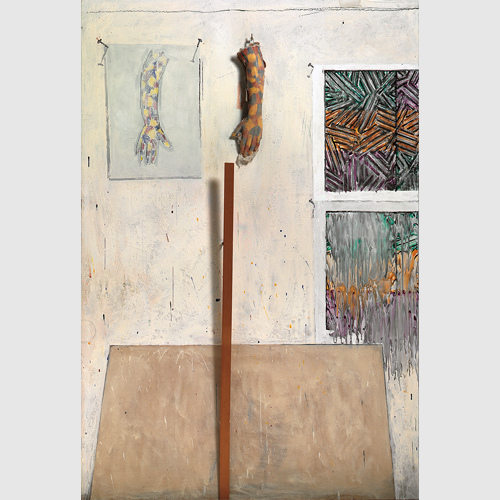

Untitled, 1984, Jasper Johns (American, born 1930), encaustic on canvas. Collection of the artist

Tour Stop: 16

Johns, Untitled (1984)

Jasper Johns

(American, born 1930)

Untitled

1984

Encaustic on canvas

Collection of the artist

This painting is executed in encaustic, a technique in which pigments are mixed with a hot wax and resin and kept warm during the painting process. The wax is subsequently burned and polished, producing a semi-glossy surface. The technique was first used in Ancient Greece, and has frequently been employed by Johns.

Untitled, from 1984, originated from a period during which Johns worked with the subjects of angst and decease. The right hand side of the painting shows the view from Johns’s bathtub, the edge of the tub barely visible as a white line in the lower right corner. On the left-hand side, patches of crosshatching form the background, creating amorphous fields of red, yellow, violet, and green. The abstract forms originate in a figure from the Isenheim Altar, painted by Mathias Grünewald between 1512 and 1516, a barely human personification of St. Anthony’s fire, a disease that was later discovered to be caused by a fungus on rye. The suffering figure, with its bloated belly and skin covered with boils, is turned upside down by Johns and fragmented into interlocking puzzle pieces filled with hatch marks.

The unstable, fragmented and vulnerable body makes up one of the painting’s subjects. Across the front of the image, Johns has included three fields of red, black, and yellow color, enveloping sketches drawn from cast body parts, (like those seen in Untitled from 1974). Other borrowed images include a Barnett Newman print at the upper right, a Swiss avalanche warning sign, two ceramic vessels, and an optical illusion that oscillates between a young maiden and an old crone as one stares at it. Behind the ambiguous female is a possible allusion to Munch’s Madonna: a pattern of light-green sperm swimming against a darker green ground.

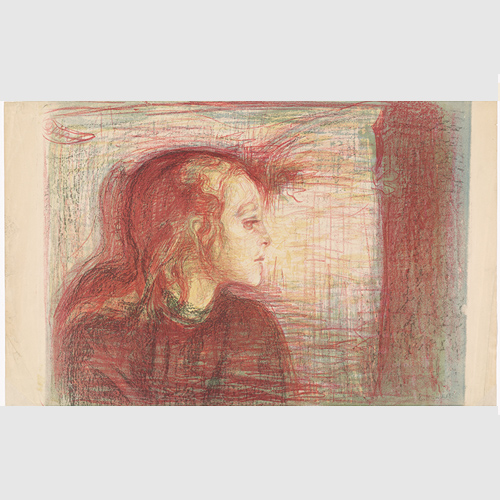

The Sick Child I, 1896, Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863–1944), lithograph. Munch Museum

Tour Stop: 17

Munch, The Sick Child I (1896)

Edvard Munch

(Norwegian, 1863–1944)

The Sick Child I,

1896

Lithograph

Munch Museum

This lithograph is based on Munch’s breakthrough painting from 1885–86. In this image, Munch departed from the naturalist mode to arrive at a more expressive and personal style of painting. The image is rooted in the memory of Sofie, Munch’s one year elder sister who died from tuberculosis at the age of 15 in 1877. Munch employed a sitter, the maidservant Betsy, who was described as transparently pale and skinny after having endured rickets. Munch was to paint the motif a total of six times during his career.

Munch made his debut as a printmaker in 1894, and made the first printed version of The Sick Child, an etching in the reverse, that same year. That Munch repeatedly returned to the motif in many versions demonstrates that the motif was of particular interest to him. His recurrent revisiting of the subject has been interpreted as the manifestation of an enduring process of mourning marked by repetition compulsion, through which the trauma of loss is relived again and again.

Hospital Ward, 1897–99, Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863–1944), oil on unprimed canvas. Munch Museum

Tour Stop: 18

Munch, Hospital Ward (1897–99)

Edvard Munch

(Norwegian, 1863–1944)

Hospital Ward

1897–99

Oil on unprimed canvas

Munch Museum

“Disease and Insanity and Death were the black Angels that stood by my Cradle,” Munch once wrote. And indeed, illness, death and transcendence are recurrent themes in his art. During the 1890s, Munch went beyond depicting images of illness from his own family and sought out psychiatric hospitals and medical practices, looking for motifs like Inheritance (1897–99) and Women in the Hospital (1897).

Perhaps this wasn’t altogether surprising, as Munch had followed his father, a military surgeon, to work from an early age. As early as 1884, while visiting his father in the army base Helgelandsmoen, Munch painted a picture from a sick ward with two patients and a nurse. In the years leading up to this painting, The Hospital Ward, he had developed a more abstract and schematic pictorial style. As far as we know, the painting was never exhibited in Munch’s lifetime.

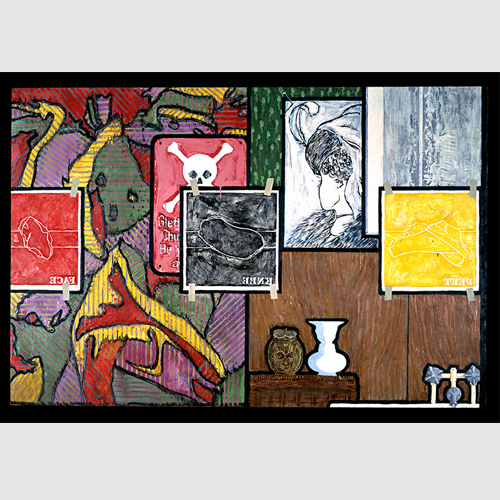

In the Studio, 1982, Jasper Johns (American, born 1930), encaustic and collage on canvas with objects. Collection of the artist

Tour Stop: 19

Johns, In the Studio (1982)

Jasper Johns

(American, born 1930)

In the Studio

1982

Encaustic and collage on canvas with objects

Collection of the artist

In the Studio, a mixture of drawing, painting, and sculpture, is saturated with personal references, beginning with the title, which evokes Johns’s studio surroundings. Like the Savarin variations, the work plays on degrees of abstraction. As the wax arm hanging to the right of the picture is an abstraction of a real arm, so the drawing next to it, in reality a painting mimicking a drawing, is an abstraction of the wax arm. At the bottom of the canvas, a large beige shape resembles the reverse of a painting leaning against the rest of the picture. Clashing with this illusionistic portrayal of space, a long strip of wood leans out several inches from the surface, casting a straight shadow across the wall and the image within the image, in this way countering the illusion of depth. This work marked the end of Johns’s ten-year long exploration of crosshatching, which from now on only appears as an element in other, more personal images.

Starry Night II, 1922–24, Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863–1944), oil on canvas. Munch Museum

Tour Stop: 20

Munch, Starry Night II (1922–24)

Edvard Munch

(Norwegian, 1863–1944)

Starry Night II

1922–24

Oil on canvas

Munch Museum

Munch painted his first painting, entitled Starry Night in the summer of 1893 in Åsgårdstrand. The group of melancholy and blue-tinged paintings made many years later, between 1922 and 1924, have several points of resemblance with their distant predecessor. The paintings share a certain firmness of composition, soft and undulating lines, a blue palette, and a poetic and melancholy timbre. The later Starry Night paintings depict Munch’s snow-clad gardens at Ekely, on the western outskirts of Oslo. In this painting, Starry Night II, we gaze out from the top of the veranda stairs over the wintry garden with its trees and hedges and towards the city with its shimmering windows. The painting is marked by shadows, and the trees and bushes rise darkly against the glowing background. One of the newel posts casts a shadow resembling a human form on the snow below. Falling against the handrail is the dark shadow of a man’s head, possibly Munch’s own.

The painting is often associated with Henrik Ibsen’s play John Gabriel Borkman from 1896. Munch took great interest in the play and spoke of it as the most vivid evocation of a winter landscape in all of Scandinavian art. After failing others and being let down himself, Borkman ends his lonely existence by going out into the snowy garden from where he gazes onto the city lights, musing, at the moment of death, that the inhabitants of the city will one day clear his name. Munch regarded the play as Ibsen’s self-portrait, conveying his sense of being ignored and misunderstood upon returning to Norway after winning fame abroad. Munch likely identified with this fate. He had found the reception by his critics to be rather tepid when he returned to Norway in 1909 after many years abroad.

The Seasons (Winter, Fall, Summer, Spring), 1985 & 1986, Jasper Johns (American, born 1930), encaustic on canvas. Robert and Jane Meyerhoff Collection

Tour Stop: 21

Johns, The Seasons (1985 & 1986)

Jasper Johns

(American, born 1930)

The Seasons (Winter, Fall, Summer, Spring)

1985 & 1986

Encaustic on canvas

Robert and Jane Meyerhoff Collection

After he had completed Between the Clock and the Bed, Johns took a turn towards a more figurative expression, his works now evoking his personal life more than in the past. This development is apparent in The Seasons from 1985–86. The series consists of drawings, prints, and these four large canvases executed in encaustic, each representing one of the seasons. The series also forms the backdrop for Johns’s investigation of changes and transitions in his own life, when he moved from one residence to another and opened a new studio.

Johns drew the dark contour of the male body appearing in the paintings after his own shadow. The presence of elements like stars, as well as rain and snow, tell of the passage of time and the changing of the seasons while the hand appearing to move across a dark disc, mimics the hands progressing across the face of a clock. The distinct use of the human shadow has been traced to Picasso’s influence, but may also be inspired by Munch, who employed shadows as an important element in his work, in particular his self-portraits.

Several features of The Seasons seem to summarize themes and artistic concepts that were of central interest to Johns throughout his artistic practice up to this point, such as the implicit reference to Marcel Duchamp through the depiction of Mona Lisa, the appearance of the American flag, and various optical illusory figures. This exhibition marks only the second time these four canvases have been seen together since Johns’s retrospective in 1996.