ABOVE:Natural Bridge, Virginia, 1860, David Johnson (American, 1827–1908), oil on canvas. Private Collection.

BELOW (l to r): Johanna Minich, Victoria and Dean Ferguson, and Chris Oliver.

This summer, VMFA will host a free program that explores the complex legacy of the Natural Bridge from different perspectives. Event details will be posted on VMFA’s website as they become available. Here, a preview of that conversation is offered in a Q & A led by Dr. Johanna Minich, VMFA’s Assistant Curator for Native American Art. She asks Dr. Christopher Oliver, curator of Virginia Arcadia and VMFA’s Assistant Curator of American Art, and Victoria and Dean Ferguson to share their insights in a dialogue about the art exhibition and the Natural Bridge itself as a site of historical and cultural significance.

Johanna Minich: I know discussions happened early in the VMFA exhibition planning process on how to include the indigenous presence in the overall exhibition theme. Chris, as the curator of Virginia Arcadia, can you tell us a little bit about how this collaboration came about?

Chris Oliver: As I was assembling a checklist of potential works to include in the exhibition, it was very clear for whose enjoyment these landscapes were intended. These landscapes were created by European and European American artists for a European and European American audience. Overall the inclusion of figures is usually quite sparse with on only a few occasions indicated to be Native Virginians, and never do they appear with any fidelity to the historic reality. Since the exhibition is interested in a major landscape site in Virginia and its depiction over about 120 years, it seemed absurd to avoid the idea that there is a centuries-long history that involves the Monacan Nation. We were fortunate to be able to engage Victoria as a community consultant to help us better understand and articulate the importance of the site as a cultural historic landmark, and this context is presented at the beginning of the exhibition for visitors to consider as they view the works of art.

Johanna Minich: Victoria and Dean, can you tell us about your involvement with the Natural Bridge? Your work there has spanned over 20 years, and you have been in a unique position to listen to visitors’ ideas about both the Monacan people and the Natural Bridge when they visit the site. What is something you want people to understand about the Natural Bridge as a cultural historic landmark?

Victoria and Dean Ferguson: In the summer of 1999, the Natural Bridge Hotel contacted the Monacan Nation to discuss developing an exhibit on the Natural Bridge property. The tribe contacted us about the meeting. We were already involved with an Eastern Woodlands exhibit at Virginia’s Explore Park. We decided to attend the meeting and give them a proposal for developing the Monacan Exhibit. During the meeting the hotel representative, Dave Parker, and the tribal representatives decided to accept the proposal for the village. On November 1, 1999, the first workers began to build what would become the Monacan Exhibit at Natural Bridge.

The Natural Bridge is ancient, caused by millions of years of wind and water. When the first humans set eyes upon it for the first time thousands of years ago, long before the first Europeans settled here, the Bridge had already formed and was already ancient. It probably looks the same today, minus the sidewalks, as it did then. The age itself is humbling. A burial site has been documented just above the great rock bridge. The ancestors’ bodies were laid to rest there, and it is important that the tribes have stewardship and the right to conduct ceremonies to acknowledge those who came before us. The burials speak specifically to the importance of this place and the cultural connection. Burial sites tie us to our ancestors and to the land on which they rest. For centuries indigenous people have performed ceremonies at burials. Natural Bridge is recognized as both a Virginia and National Historic Landmark but is not listed as a monument whose cultural significance is protected by the Antiquities Act. At places with this protection, tribal members with ties to the land are usually afforded access to the site for ceremonies. Monacans understand the cultural connection to the Natural Bridge in reference to our tribe and history. Designating the Natural Bridge as a cultural historic landmark for the Monacan people and including it on the list of national monuments protected by the Antiquities Act would be an important step in acknowledging the importance of the first people of the region.

Johanna Minich: In so many of the images of the Natural Bridge, there is an implied religious reverence for the location, suggesting the site has, or should have, a spiritual importance. Can you talk about the various ways Christianity has been “overlaid” onto the representations, or is there one work in particular that stands out as such?

Chris Oliver: Yes. For many of the landscape painters in the exhibition, who practiced a variety of Christian faiths, there was a direct connection between the landscape and a divine presence. Perhaps this is no more straightforwardly addressed than in Edward Hicks’s Peaceable Kingdom. In addition to being a painter, Hicks was a minister in the Society of Friends, and his paintings often represent his beliefs playing out within a distinctly American landscape. In this work, Hicks includes a quotation from Isaiah, which talks about an “everlasting peace” gained through faith. Incongruously, Hicks has placed a scene of William Penn and other English colonists executing a treaty of peace with the Native Lenape near Philadelphia in 1683. The actual distance between the Natural Bridge and the site of the treaty was not important for Hicks. Rather, the presence of the Bridge is a divine approbation of the peace Hicks believed was achieved in this new American Eden, however disparate from historic reality that may have been.

Peaceable Kingdom, 1822–25, Edward Hicks (American, 1780–1849), oil on canvas.

ⓒ Mead Museum of Art/Amherst College. Photo credit: Petegorsky/Gipe photo

Johanna Minich: Can we point to any examples of how the site has been represented by Native people who lived there and continue to live in the area, either in written, oral, or visual histories?

Victoria and Dean Ferguson: There is information about the Natural Bridge and the Monacans contained in a story often referred to as the Monacan Legend of Natural Bridge. The story appears to go back into the 1800s, but it has been difficult to trace down the exact origin. It appears to have been kept [as an oral history] among the Algonquin and states that the Monacans were in a battle with Algonquin speakers when the story originates.

Johanna Minich: In Virginia Arcadia, a text panel notes the existence of early prints that illustrate the Natural Bridge and include Native people in the landscape. I didn’t see such depictions in the exhibition, so can you describe those prints to us? How are the people represented in them?

Chris Oliver: Often when European American artists included Native American figures in scenes of the Natural Bridge, they enhanced the figures’ appearance as “other” by clothing them in long flowing robes or even vaguely Middle Eastern dress, which held particular interest at the time. It didn’t really matter if the look was based on reality; it was about indicating a non-whiteness that also had flourishes of exoticism. The result is a reductive and ultimately harmful deployment of racial stereotyping.

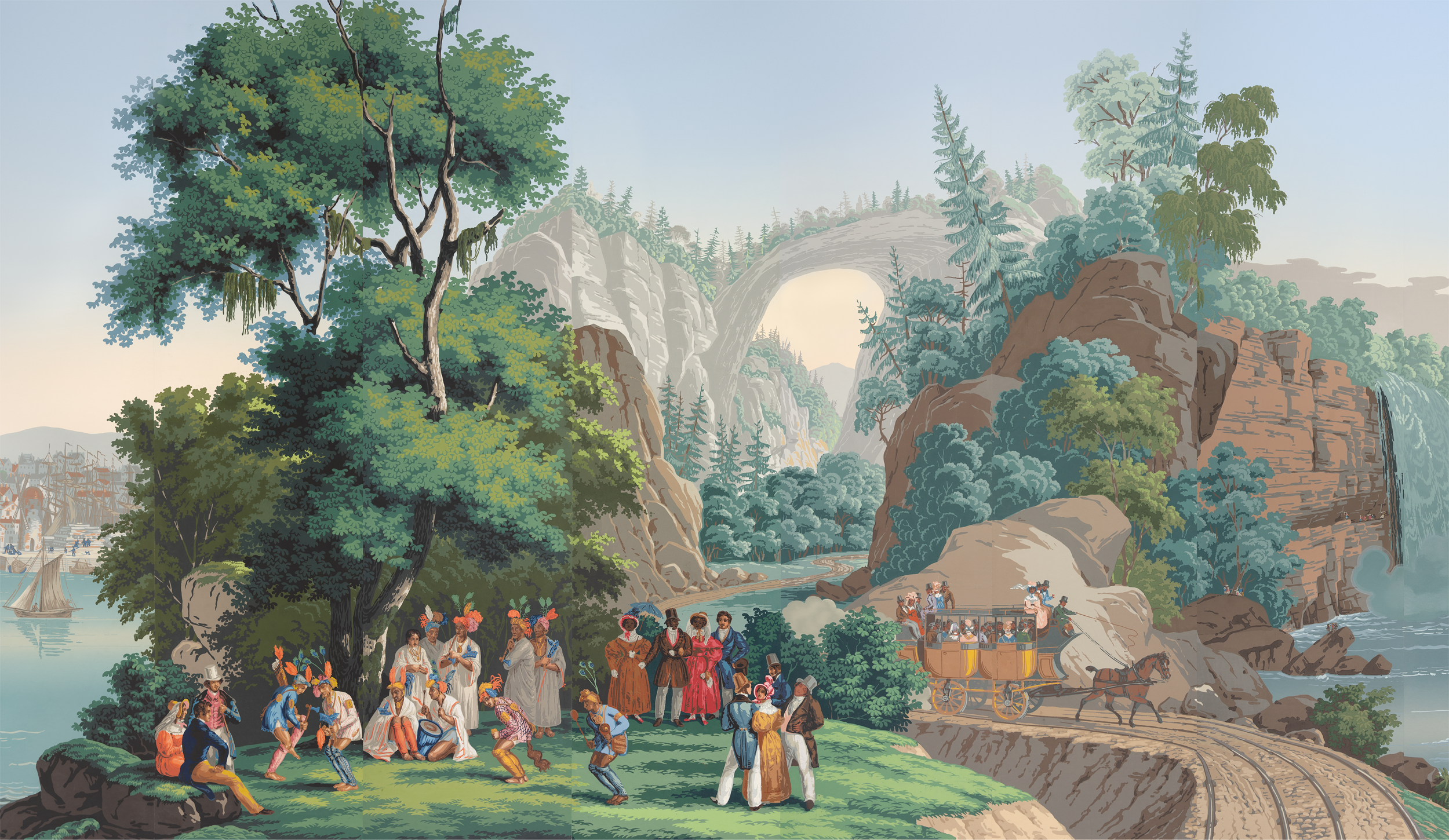

Johanna Minich: Can we also perhaps talk a little bit about the French wallpaper design that includes the representation of Native people “performing” for Euro-American tourists? That image in particular stuck with me. I wonder what thoughts you have about this imagery.

Victoria Ferguson: In this particular content I believe the artist tried to depict the Native clothing in a way that made it more of a costume. This regalia is not what the Native people would have themselves been wearing.

Chris Oliver: Yes. Some of those conventions of depicting Native dress as exotic, as I mentioned before, appear in these images. It is, of course, a malignant fantasy. The wallpaper, which was produced and designed in France in 1834, is emblematic of some colonial desires already embedded in French visual culture, which is a pastiche of Asian and North American dress—distinctly not European. The performance is also done in front of an audience that is racially diverse and may be an optimistic hope for emancipation in America. But it still places the Native population as a group of people who are there only to be inspected. The hierarchy of people within this image is reinforced by dress and comportment.

Natural Bridge from Vues de l’Amérique du Nord, 1835, Zuber et Cie (French, 1797–present),

color woodblock-printed wallpaper. Image: Courtesy of SFO Museum

Johanna Minich: In many examples of American landscape painting, artists would combine various elements of “plein air” sketches to create the “ideal” landscape. And in those, they seem more comfortable placing Native people within those landscapes, almost like a prop to convey that message of the “vanishing race.” With images of the Natural Bridge, artists seem more reticent to put Native people in the image. I wonder if any of you had thoughts on why. Would it be because this is such a specific location? They were already touting America as a land of beauty and unspoiled wonders that would appeal to tourists and adventurers. American painters were promoting the idea of “new discovery” and perhaps placing Native people within this landscape would spoil that idea that there were still undiscovered wonders.

Chris Oliver: That’s a very interesting question. I think you’re right to observe that while Native American figures are included in some Natural Bridge landscapes, it seems to be with far less frequency than some of the other sites depicted in contemporary art. I think with some of the later, say post-1850, works of art, the sense of playing up the spot as a site for genteel relaxation may preclude the inclusion of any identifiably Native figures. It would only be in the earlier works, when there was still a sense of the Natural Bridge as presumably unspoiled, would some sense of Native figures be included. Indeed, the inclusion of such figures was typically a very shallow and pandering act, a mere shorthand for how “wild” the landscape may be.

Victoria Ferguson: I have been involved with the Monacan Exhibit since its very beginning. I walked under the bridge daily and after a while it became mundane as I concentrated on what my day would look like and what I needed to get accomplished. On this particular morning, the fog was all around. There was a slight glimmer of the outline of the sun illuminating the sky. As I walked under the Bridge I turned to look back and it was a beautiful sight. Almost everything was in a shade of limestone gray except the green tree growing out the side. It always amazes me how a tiny seed can embed itself in the tiniest of crevices and become a tree to provide oxygen for us. There it was the fog of our ancestors and the tree breathing its own life. It was such a sense of calmness because the trail was empty. I took the picture and knew immediately I had something special. I wondered if the breath of those ancestors buried and disturbed above the Bridge was among the breath Mother Nature was showing me that day.

Chris Oliver: And I think this really ties into one of the larger ideas within the exhibition about image making particularly at one site. Here, Victoria is so intimately familiar with the Natural Bridge, and in the process of creating this work, she’s bringing with her all of her past knowledge and imbuing this work with a very poignant meaning. The Natural Bridge is monumental and enduring and a wonderfully apt icon for the spirit of the Monacan people, then and now.

Breath of the Ancestors, digital photograph,

courtesy of Victoria Ferguson

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts is currently working on a formal land acknowledgment, which is in the process of full approval through all eleven tribes recognized federally and by Virginia.

The Commonwealth of Virginia was one of the first points of contact between Indigenous peoples and European settlers, and VMFA acknowledges the presence of the Powhatan Confederacy and the Monacan Nation on the land on which the museum now stands.