This summer, three interns were selected to complete an internship at VMFA’s Center for Advanced Study in Art Conservation. Generously funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) as part of the “Connect to Conservation” program, the internship was designed to provide training and professional development to individuals considering a career in art conservation. The interns, Morgan Shedd (VCU, ’18), Aleyah Grimes (VCU, ’19), and Megan Mezera (University of British Columbia, ’22), completed projects with the Sculture and Decorative Arts, Paintings, and Paper conservators at VMFA, and they describe a favorite experience below:

Conservation in Action : Maintaining the Sculpture Garden at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Morgan Shedd

IMLS Conservation Interns, Morgan Shedd, Aleyah Grimes, and Megan Mezera (from left to right), brush-clean Seymour Lipton’s 1966 bronze work, “Oracle.”

IMLS Conservation Interns, Morgan Shedd, Aleyah Grimes, and Megan Mezera (from left to right), brush-clean Seymour Lipton’s 1966 bronze work, “Oracle.”Regular cleaning and maintenance is essential to the upkeep of an outdoor sculpture collection, such as the one displayed in the sculpture garden at the VMFA. This ensures that the artworks living outside can not only stay protected, but can also withstand various weather elements. Virginia is fortunate to experience four seasons of weather: everything from 90-degree heatwaves to a foot of snow. While this is great for R-VA, these extremes of exposure can take a toll on a work of art. A museum campus also sees events with a large number of visitors, pests and animals, and areas where security measures do not prevent visitors from interacting more directly with the works. Unfortunately, spilled beverages, oils from fingerprints, and pet accidents happen; outdoor sculpture conservators have seen it all!

During our internship this summer at the VMFA, Andrew Baxter, an internationally renowned sculpture conservator who has worked on across globe, introduced us to the care routine for maintaining these works.

Sandro Chia’s “Man and Vegetation” was the star of the day’s annual cleaning and treatment.

Sandro Chia’s “Man and Vegetation” was the star of the day’s annual cleaning and treatment.Before treatment can occur, Mr. Baxter assesses damages and conditions in a report that evaluates the need of each sculpture and presents a treatment proposal to steer what route the cleaning will take. After a clear plan is determined, we can get down to business!

Conservator Andrew Baxter demonstrates scrubbing of Sandro Chia’s “Man and Vegetation.”

Conservator Andrew Baxter demonstrates scrubbing of Sandro Chia’s “Man and Vegetation.”Following examination of Sandro Chia’s monumental bronze work, “Man and Vegetation” (1983), the other interns and myself used a neutral detergent solution mixed with water to hose down and clean the sculpture. Using non-abrasive brushes, we scrubbed any surface dirt and grime away from the surface. During this step, extra attention was paid to all crevices that could potentially harbor spider webs, animal nests, or areas where dirt could easily accumulate between the yearly cleanings.

After the surface cleaning, it was essential to hose down the sculpture with water a second time to ensure that no soapy residue was left over before a layer of protective wax was applied over top. Mr. Baxter stated that while the weather conditions are not comfortable to work in, the summer months are perfect to clean the sculptures, as the sun helps dry any residual water off of the sculptures before waxing. This way, there is no moisture trapped between the metal and the protective coating. The heat also helps the wax melt into and seal any micro-cracks in the surface.

IMLS Conservation Interns Aleyah Grimes (front) and Megan Mezera buff the applied wax coating into every crevice.

IMLS Conservation Interns Aleyah Grimes (front) and Megan Mezera buff the applied wax coating into every crevice.After letting the work dry, we applied a protective wax, custom-tinted with light-stable dry pigments, to every inch of the work using brushes in a circular pattern to mimic the grain of the bronze casting. After waxing, a soft, lint-free cloth was used to buff the wax into the metal.

As outdoor sculptures are usually quite large, treatment of a sculpture such as “Man and Vegetation” can involve using equipment like ladders and scaffolding, to reach every part of the surface. No area can be left out, so as to ensure that the sculpture does not differentially weather and that the patina remains consistent with the artist’s vision.

Conservator Andrew Baxter uses a ladder to reach every inch of this very large sculpture!

Conservator Andrew Baxter uses a ladder to reach every inch of this very large sculpture!Each of the outdoor sculptures at the VMFA is cleaned at least once per year. However, as not all of the works reacts the same way to the same maintenance procedure, each work requires specialized treatment plans individual to the materials used to create it.

Careful maintenance and vigilant stewardship can ensure that these works of art, in their high-traffic locations, will not deteriorate over their lifetime at the VMFA. Sculptures are energized by their environment, and this way, they can remain securely in-situ. The next time you are here, stop by the Sculpture Garden at the VMFA and bask in their glory, but remember to enjoy without touching!

Paper Cleaning & Washing

Aleyah Grimes

The object I worked on in the paper conservation department, an etching in black ink on laid paper and depicting four farm animals, is not accessioned but was donated by a private collector.

As the object was fairly soiled, I first performed a general surface cleaning that included dirt removal with a vinyl eraser while sweeping the excess particles off the paper surface with a clean, soft-bristled brush. While I experimented mainly with the eraser, alternating between an eraser holder and rubbing eraser shavings with my washed, ungloved fingers against the surface, I found that the most successful cleaning method was a cosmetic sponge made of polyurethane, gently dabbing it against the surface. Though relatively straightforward, this process required a great deal of focus and a steady hand.

Surface cleaning using vinyl eraser and cosmetic sponge

Surface cleaning using vinyl eraser and cosmetic spongeThe most surprising thing I learned while preparing the paper for washing was that if the paper is humidified beforehand, it will significantly reduce buckling when the paper is submerged. This is due to the fact that the humidification process is the slow and controlled introduction of water vapor, which allows the paper to gradually adjust to an increased water content. Deionized water is highly reactive and fairly acidic so in order to neutralize it, we first used a meter to measure the water’s pH against a calibration solution of known pH. To adjust the pH of the water, we slowly added calcium hydroxide until the solution reached a pH of 7. Once the water was neutralized, it was added to a sprayer to be used for humidifying the object.

The print was placed between non-woven polyester sheets for support while it was humidified between two pieces of GoreTex. The membrane in GoreTex allows only water vapor to pass, preventing liquid water droplets. A plastic polyethylene sheet was placed on top and the object was left to humidify for approximately 20 minutes, until the paper sheet had completely relaxed.

Humidification Chamber

Humidification ChamberBefore the object could be washed, Tek-Wipe (a synthetic material used for capillary washing) was placed in a clean plastic tub and a shallow pool of the pH-neutral deionized water was poured on top, just enough to evenly wet the paper. Next, we used our clean, ungloved hands to smooth all the wrinkles and bubbles out of the paper and then used a damp brush to go over it once more to ensure a flat, even surface. The object, still supported between the two sheets of polyester, was then taken out of the humidification chamber, placed onto the Tek-Wipe, and gently brushed into flat, even contact with the Tek-Wipe. After rolling the polyester back at a low angle to keep from disturbing the object, the object was then lightly sprayed, re-covered, and brushed again. During the washing, discoloration that was not removed during surface cleaning was dissolved from the object.

Object soaking on Tek Wipe

Object soaking on Tek WipeAfter completing the paper washing, the object, still encased in the polyester, was removed from the Tek Wipe and placed on a mesh-lined drying rack, where it remained until it was dry and ready to be flattened. Reduced discoloration and soiling was evidenced by a light ring of discoloration left behind on the Tek Wipe upon removal. Air drying allowed for the cellulose fibers to realign naturally, and the increase in hydrogen bonding between the fibers is what adds strength and flexibility to the sheet.

During this activity, I learned that paper is far more resilient than I had previously assumed. I was particularly fascinated by the object’s ability to endure exposure to moisture, despite its soiled and tattered appearance. I would say this treatment was one of my favorite activities that I participated in during my internship: I found the amount of attention and delicacy put into the repeated spraying and brushing of the object both rewarding and strangely meditative.

At the Intersection of Art and Science

Megan Mezera

In my experience, I have encountered numerous people who believe science and art are completely opposite disciplines; however, there are a great deal of careers, including art conservation, that rely heavily on both. To analyze a work of art, art conservators can use instruments, such as a spectrometer or x-ray imaging, that are typically found in laboratories or hospitals. These tools not only help art conservators understand the structure of a work of art, but they can also help them understand the techniques an artist used when creating a piece.

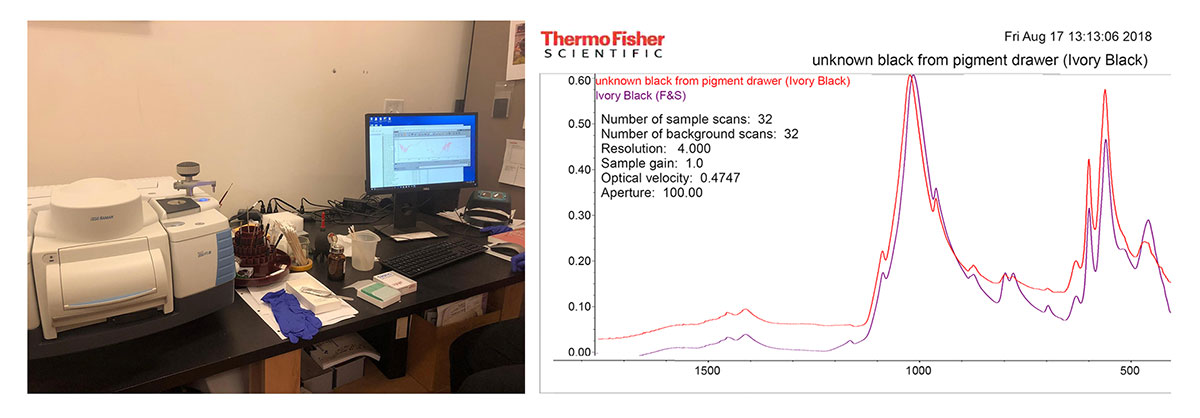

Thermo Nicolet IS50 FTIR with Raman module (left) with a spectrum collected identifying ivory black (right).

Thermo Nicolet IS50 FTIR with Raman module (left) with a spectrum collected identifying ivory black (right).Spectroscopy is a technique art conservators use to determine the chemical composition of an unknown material, with fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and x-ray fluorescence (XRF) being the two main types used at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. FTIR records the radiation absorption of a sample and creates a corresponding spectrum of those values. From there, the software will compare the unknown spectrum against those in a library to produce a list of possible materials present in the sample. XRF measures the characteristic fluorescence that is released by an element in a sample when x-radiation is introduced to it. Afterwards, the program will generate a spectrum of the fluorescence, each peak corresponding to a certain element, from which an art conservator can analyze and determine the elemental composition of their sample.

Morgan Shedd, Megan Mezara, and Aleyah Grimes perform IR imaging of a painting with Carol Sawyer, Senior Paintings Conservator.

Morgan Shedd, Megan Mezara, and Aleyah Grimes perform IR imaging of a painting with Carol Sawyer, Senior Paintings Conservator.These are just a few of the instruments and techniques art conservators have at their disposal, and the resulting discoveries are extremely important to understanding the chemical composition of materials, their conditions, and how a work of art was created.