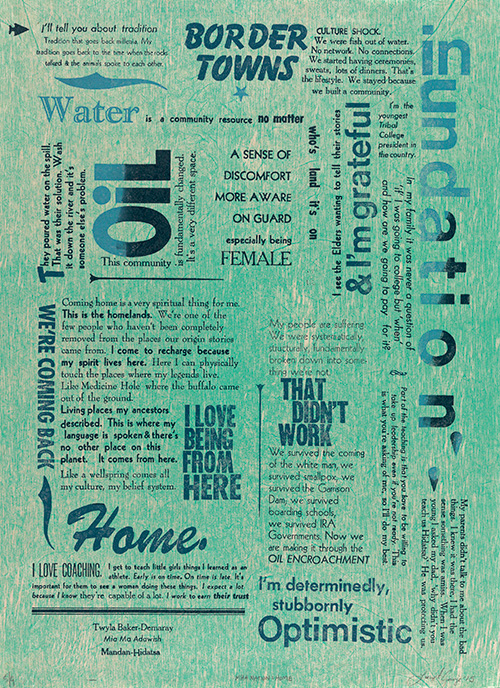

In Our Own Words: Native Impressions, a companion exhibition to Hear My Voice: Native American Art of the Past and Present, features a series of prints intended to highlight the life experiences of Native Americans living in North Dakota today. Daniel Heyman, whose previous work dealt with provocative social and political issues, collaborated with Lucy Ganje, who has family ties to tribal nations in North Dakota, to produce the portfolio under the guidance of master printer Kim Fink. The two artists listened to members of North Dakota’s four remaining tribal nations talk about their personal and family histories. The series of 26 prints on handmade paper is made up of twelve pairs of portraits and broadsides that include excerpts from these interviews, plus a title page and colophon.

In Our Own Words is curated by Dr. Johanna Minich, Assistant Curator of Native American Art, who discussed the project with Heyman and Ganje in a recent interview.

What led to this collaboration?

D.H.: I had been out to Grand Forks several times before I officially met Lucy. My portfolio of drypoint portraits of Iraqi survivors of torture from Abu Ghraib prison was on display at the North Dakota Museum the first time I went to Grand Forks, and while I was there, I started to work with Kim Fink, head of printmaking at the University of North Dakota and master printer at Sundog Multiples. I wanted to make some kind of visual statement about the diversity of the US, including places as remote from large cities as Grand Forks, where I returned two or three times. In October of 2014, I met Lucy who asked if I would consider working with her doing a similar project portraying contemporary Native Americans being interviewed about their lives. Kim, Lucy and I went to work lining up funding and making connections with the 4 reservations in North Dakota and we were on our way by the spring of 2015.

L.G.: I was aware of Daniel’s work and admired his artistic commitment to human rights and the ways in which he used his art to raise awareness and honor displaced and marginalized people and communities. With that in mind, and because I had spent my life working in and around Native American communities, I approached him and Kim Fink with the idea of doing a project that would help dispel the stereotypes of Native people and educate the public about the displacement and historical trauma that continues to plague Native peoples.

How were these individuals chosen for this project?

L.G.: We asked each tribal college to assist us in identifying three citizens of the tribal nation the college served, people who they felt had unique and noteworthy stories to share. These stories included narratives of language loss and preservation, boarding schools, cultural preservation and the struggle for sovereignty.

Daniel, how did your experience working on this project compare with some of your other projects?

D.H.: To start with, my motivation was completely different, and by the time I got to North Dakota I had much more experience than I did when speaking with and drawing Iraqis. I was motivated to find out directly from contemporary people what their lives are like today, and I was less interested in highlighting immoral government policy. I wanted to find out more about who Natives are, what motivates them, how they might see their own history and live with it in the present, how their goals evolve and how they see themselves in the context of their families, their communities and the larger context of the US. I found once again that I knew very little, and that listening was an effective and exciting way to learn about people.

As to the technique, for this project I used woodblocks made of simple over the counter plywood. This is a relief process that I am always excited to work with as it affords me great flexibility and charm I think in color and composition. I was excited to work full on with Kim and his assistant Josh Tangen who helped us endlessly, and I was very excited to see what Lucy would do with the text given to us through the interviews.

Lucy, can you explain how graphic design has been used as a social or political tool?

L.G.: The power and impact of graphic design is sometimes dismissed because it is also a tool of consumerism. But in fact graphic design has a very long history and an extremely active presence in social and political movements. Graphic design and letterpress printing developed and thrived as tools of political dissent and public discussion. In the 20th century alone graphic design helped foster the movement against the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, the movement for Civil Rights and the Women’s Rights Movement. Graphic design served to fuel the Arab Spring and Idle No More, a First Nation’s activist movement begun in Canada.

What is the importance of the words in the images you create and why did you decide to create two separate prints for each story?

D.H.: I was aware immediately that my prints did not need to carry all of the written content of the stories we heard during the interviews, and I could be briefer and more selective in the words that I chose to print as I knew that viewers could look to Lucy’s broadsides for the context of the words that I captured for a fuller understanding. In this way while looking at the relief prints the words were slightly more open, more poetic, less specific, but somehow also landed more of a punch once the viewer did go back and get the context from Lucy’s broadsides. I want these portraits really to be about individuals who speak for themselves in describing their lives. I am resistant and uncomfortable with the idea that my work represents anyone in any accurate manner, and the words help us get closer to who we are looking at.

L.G.: The combination of word and image to tell a story deepens understanding and heightens the impact of the message. The letterpress broadsides containing oral histories of the person portrayed, alongside their portrait allows the viewer to move back and forth between word and image. The design and placement of the words and phrases, which often take a circuitous path, mirror the roundabout way in which the narrative sometimes proceeded, leading the viewer to tend carefully to the story the person has to tell.

Can each of you speak about one of the pairs: Who is the subject? What resonates with you personally about his/her story?

D.H.:

I had a hard time choosing a specific person to talk about because I find all of these people and their stories so compelling. But I chose Pat Walking Eagle because her story, the part that I tried to convey relates so closely to my own background, and though there is a similarity, there is also a trap that many people have fallen into. Pat describes hearing the Dakota language being spoken fluently around her as a child, particularly from her grandmother, but Pat herself never learned the language. Loss of language, is a constant theme in these interviews, and in particular a sort of regret and sadness for a loss that is witnessed in one’s own lifetime. In the carving of her portrait, I picture Pat upright and rather formal, which is how I found her. The writing that swirls around her is at times clear and at times quite hard to read — fuzzy, like the static of an old TV. It seems to match the subject of language being lost and no longer so easy to capture. Pat describes the desire of parents to protect children from the pains they suffered because of the language they spoke, and so they made the heart-wrenching decision to not teach their children their native tongue. This, more than almost anything, was how these sitters described loosing contact with their cultural roots.

This is similar to my own experience as each of my grandparents spoke Yiddish as a native tongue, and then in an effort to help their children and themselves become more “American” they refused to speak this language or pass it on. Though this is a similar experience, and I have no access to the language of my forefathers and mothers, Native Americans are not immigrants, they are the first inhabitants of their own land. We make a huge mistake asking how the Native communities can better fit in to our culture; they don’t have to. They have been here all along.

L.G.: This is difficult because each person and their life experiences is so unique and captivating. But while there were so many thought-provoking political and cultural accounts, I think the one that stays with me is Cissy Dunn’s. Cissy, a business owner on the reservation, serves fresh salads and espresso drinks at a small café called “My Aunties.” So named because an “auntie” in her culture is an important figure, bearing both love, respect and authority. It was clear she faced many challenges in her life, but each story of personal and professional grief was followed by her laughter and another story telling us what she had learned because of what she had been through. In her presence, one could not help but feel hopeful about human capacity.