Ancient Egyptian Culture

Learn all about Egyptian land, religion, writing, trade, and of course mummies!

Use the on-site version of this resource to guide students through the museum’s Ancient Art Galleries: Ancient Egyptian Culture Gallery Guide.

Egyptian Civilization and the Nile

“Hail to thee, O Nile! That issues from the earth and comes to give life to Egypt!” Hymn to the Nile, ca. 2100 BC

Egypt is the home of one of the world’s earliest civilizations! More than five thousand years ago, this great civilization began to take shape in the northeast corner of Africa. Ancient Egypt was surrounded by natural borders: deserts to the east and west and the vast Mediterranean Sea to the north. The Nile River, which flowed from the south, flooded every year, leaving rich dark soil that was ideal for farming fruits, vegetables, and wheat. Egyptians grew so much grain that Egypt was called the “breadbasket” of the ancient world.

Natural Resources

Male Head, 380–342 BC, granite. Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment

Although most of Egypt is desert, the area is full of natural resources. These resources helped the Egyptians build a great civilization. The most important resource was the Nile, the river that made it possible for Egyptians to fish, grow food, and trade with their neighbors. Papyrus, a tall reed that could be made into paper, was so common in Lower Egypt that the region was called the “Land of Papyrus,” and the plant became its symbol. Other natural resources were used to create amazing works of art and architecture. The pyramids of Giza were made with nearby limestone, while granite used for sculpture was brought from nearly six hundred miles away, near the city of Aswan. Copper, a material for making tools and bronze sculpture, was mined in Sinai.

This head is carved from granite, a very hard stone that was used for important sculptures.

Hieroglyphs Ancient Egyptian Writing

The Egyptians were one of the first cultures to invent writing. They used symbols called hieroglyphs for sounds, words, and ideas. There are over seven hundred hieroglyphs! The ancient Egyptians called their writing medu-netjer, which means “words of god,” because they believed that the god Thoth invented writing. Did you know the English word paper comes from the Egyptian word “papyrus?” The Egyptians invented papyrus, a type of paper made from the papyrus plants. First the outer part of the plant was removed, and then the soft interior was cut into strips, laid in multiple layers, and pounded together. When the papyrus sheets dried, they could be written on with pigments made from plants and minerals.

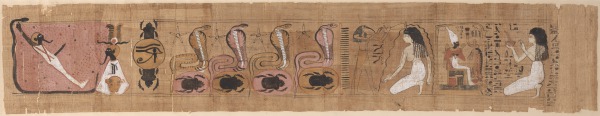

Fragment of a Mythological Papyrus Scroll, 950 – 730 BC, papyrus and tempera. Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund

Scribes, who recorded the important business of Egypt, were some of the only people who could read and write. They attended a special school to learn how to use hieroglyphs.

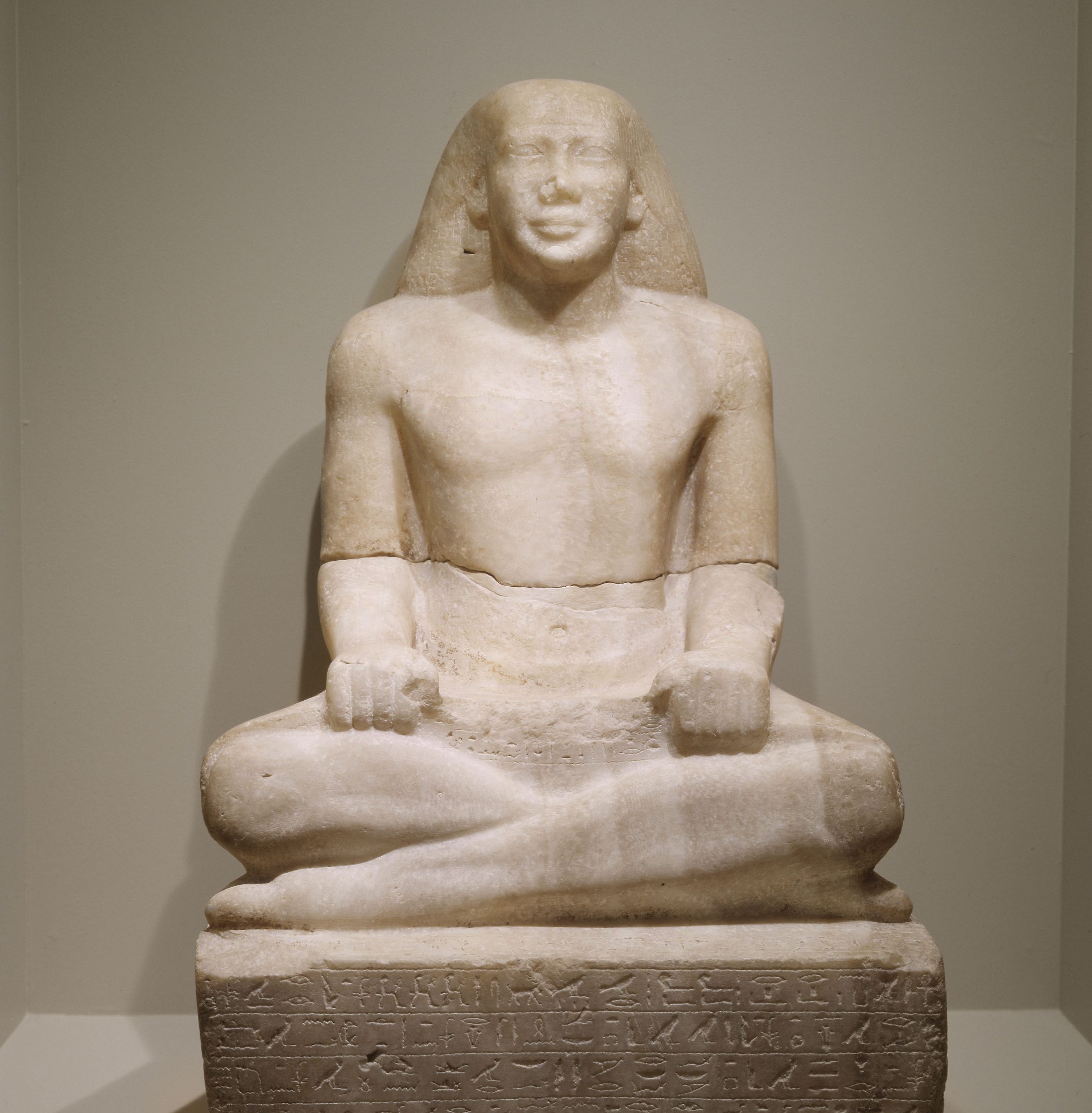

Seated Scribe, 664–610 BC, alabaster. Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund

Nubia: Egypt’s Southern Neighbor

Nubia was a region of Africa located south of Egypt in what is now the country of Sudan. Long ago Nubia was the home of the Kingdom of Kush. Like the Egyptians, Nubians lived along the Nile River, growing such foods as grain, peas, lentils, and dates. In the desert areas, they mined carnelian and other precious stones as well as metals such as gold. The Kushites traded these resources with the Egyptians for grain, vegetable oils, wine, beer, linen, and other goods. The Kushites and the Egyptians were sometimes peaceful and sometimes hostile neighbors. From 760 to 656 BC, the Kushites ruled Egypt, and King Senkamanisken ruled Kush soon after this time.

The Kushites and Egyptians created very similar art, but Kushite statues tend to look more solid, with figures having thicker legs. The rough areas of this statue were probably covered with gold, which created a contrast with the highly polished stone.

Statue of Senkamanisken, King of Kush, 643–623 BC, granite. Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund

Gods and Goddesses

Statuette of Bastet, ca. 663–525 BC, bronze. Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund

Religion was very important to the ancient Egyptians, and they worshipped hundreds of gods and goddesses! The Egyptians believed that their king, called a pharaoh, was the falcon-headed god Horus on Earth who served as the link between the gods and humans. Other Egyptian deities (gods and goddesses) were also represented as animals or as beings that were part animal and part human.

A god or goddess was usually associated with a particular animal because of shared qualities or characteristics. The goddess Bastet was known as a protector, as fierce as a mother cat protecting her kittens, so she was represented either as a house cat or a woman with the head of a cat. Sekhmet, the goddess of war, is shown as a lion or a woman with the head of a lion. Cats were so important to the Egyptians that some were even mummified!

The cat-headed goddess Bastet holds a sistrum (a musical instrument),

a basket, and a kitten in this small bronze sculpture.

What animal features and powers do you want and why? Write about it and/or draw it!

The Afterlife and Mummification

Ancient Egyptians believed that after people die in this world, they continue living in another world. Bodies were preserved, or protected, through mummification, a very long and expensive process that not everyone could afford. Mummies were wrapped and placed in coffins and buried in tombs or graves. Magic spells and special instructions were often written in hieroglyphs on coffins and in tombs to offer protection and ward off evil. Protective amulets, similar to lucky charms, were also sometimes wrapped with the mummy.

The Egyptians painted eyes on the outside of coffins so that the mummy could see the rising sun each day. The Egyptians thought that, just as the sun is reborn every morning, people are reborn in the next world.

Objects from daily life, such as vessels for storing food, sandals, games, and even razors were placed with the dead for use in the afterlife. Sometimes the objects were depicted in art, but for the Egyptians, these pictures could still be used (or eaten or drunk!) in the next world.

What objects would you take with you? Make a list.

Coffin and Mummy of Tjeby, ca. 2051-2030 BC, painted wood with linen-wrapped mummy. Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund

Meet Tjeby!

Reconstruction of Tjeby. Artwork by Jonathan P. Elias, AMSC Research, 2015

How do we know what Tjeby, VMFA’s mummy, looked like? In 2013 scientists used a CT scan (computerized tomography) to view Tjeby’s skeleton without damaging the mummy’s wrappings. A CT scan is a kind of three-dimensional X-ray that allows us to see all the details of the inside of a mummy from any angle we want. Scientists used computers to process hundreds of individual images to create a complete image of Tjeby. The CT scan showed us the size and condition of Tjeby’s bones. This allowed us to conclude that he was about five feet eight inches tall, had no signs of disease, and died when he was about thirty years old. Based on the CT scan, scientists were able to print out a 3-D version of Tjeby’s skull. They then used this model to create an image of Tjeby as he may have looked over four thousand years ago!

Egyptian Art

Egyptian artists followed a set of rules for painting, drawing, sculpting, or carving human figures in art. They used a grid that was eighteen squares tall and divided the body into eighteen equal parts from the bottom of the feet to the hairline above the forehead. This grid showed the artists how big to make each part of the body since each part was always the same number of squares. For example, the distance from the feet to the belly button was always eleven squares and from the belly button to the shoulder always five squares. To make larger figures, the squares themselves were larger, and for smaller figures, the squares were smaller. The most important figures in images are always the largest ones.

Human figures were sometimes depicted in a twisted position. The head and legs of this scribe are shown from the side, but the waist and torso are pictured from the front. This allowed the Egyptians to represent a body in the clearest possible way.

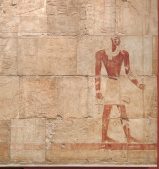

The large figure in this relief is Methethy, a nobleman who is giving orders to four servants taking an inventory of his possessions. Notice how he is much larger than the other figures.

Tomb Relief, 2475–2195 BC, limestone, polychrome. Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund

Trade

Although natural resources were plentiful in Egypt, Egyptians also traded or bartered (exchanged goods without money) with inhabitants of other lands. Egypt became the center for trade routes to and from western Asia, the Mediterranean, and central Africa. Within Egypt, the Nile River served as the main trade route. The most famous trading expedition in Egyptian history occurred during the reign of the pharaoh Hatshepsut (reigned ca. 1473–1458 BC). She sent ships south to the land of Punt, believed to be near the present-day Somali coast. A large wall relief in Hatsheput’s Temple in Egypt shows this expedition. A plaster cast of this relief at VMFA features trading vessels and goods the Egyptians brought back, such as spices, ivory, frankincense, myrrh trees, and wild animals such as baboons. This voyage was made via the Red Sea, an ecosystem with over twelve thousand species of fish. Artists depicted these fish so accurately that scientists today can recognize some of the species that still live in the sea.

Kingship

The job of the king, or pharaoh, was to maintain ma’at, a word meaning truth, order, and balance. Order had to be kept between both the Egyptian people and the gods. Although most kings were male, at least three women ruled Egypt as kings, including Hatshepsut shown above and Cleopatra VII (reigned 51–30 BC). Hatshepsut has many symbols of kingship in this image. She wears a royal headdress, or nemes, and a false beard. She holds symbols of her royal status: an ankh, a symbol of eternal (endless) life (1); the feather of ma’at (2); and a staff (3). Pharaohs were given five different names. The most important, the throne name, was given at the time that he or she became pharaoh. Hatshepsut’s throne name was Maat ka re, which meant “truth in the soul of the sun.” Re, or Ra, was the sun god.

If you could choose your name, what would it be? What would it mean?

Cast of Punt Relief, from Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el Bahri (detail), 20th century, original ca.

1480 BC, plaster. Lent by the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Egypt Is in Africa

King's Beaded Robe, 20th century, Yoruba. Kathleen Boone Samuels Memorial Fund, and the Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment

Although the Sahara Desert separated ancient Egypt from the rest of Africa, the people of this multicultural continent traded with each other across long distances and shared many common ideas and beliefs. For example, today the Yoruba (yo-roo-buh) people of West Africa, like ancient Egyptians, link their rulers to gods and goddesses.

The Yoruba king is recognized in public because of his amazing costume and crown. Many of the king’s garments feature symbols, one of which is a face representing the god Oduduwa (o-doo-doo-wah). Another symbol often found on a king’s clothing is a bird. Birds, since they can walk and fly, represent the king as a link between the orisha (or-ee-shah) or god and his people.

A symbol is something that stands for something else. What symbol would you choose to represent yourself?