Celebrate Hispanic Heritage Month

at VMFA

In celebration of Hispanic heritage month, we are showcasing diverse works from contemporary Latin American and Hispanic artists as well as works from our Ancient American galleries. We encourage you to explore the rich and varied artistic heritage of these works and VMFA’s ever-growing collections in these areas.

Please note: Works are not on view unless a gallery location is indicated.

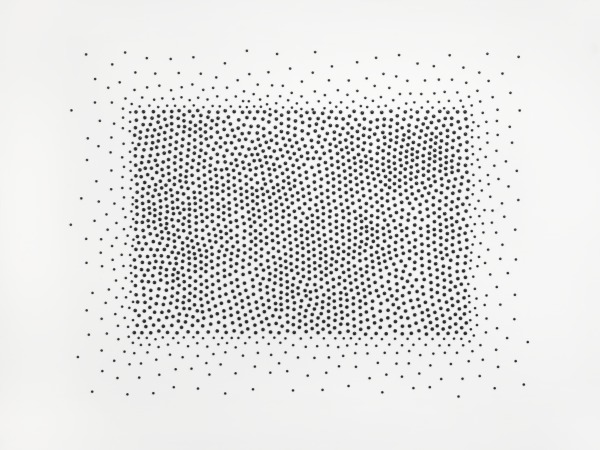

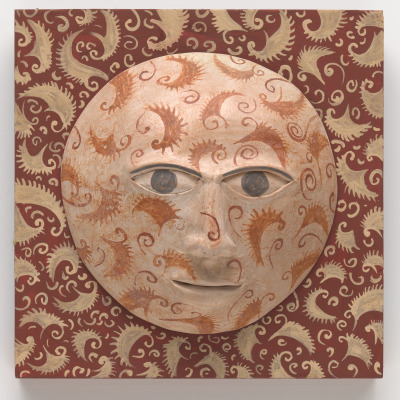

Projection screen (Black Onyx), Teresita Fernandez

Fernandez often takes elemental, natural phenomena like fire, water, ice, and smoke as her starting point. She then makes highly distilled illusions that invoke both the thing itself and blatantly artificial representations of these phenomena. In this way, her work addresses her overlapping interests in problems of perception and in the cultural fabrication of “nature.” In Projection Screen, hundreds of tiny polished halfspheres of black onyx affixed directly to the wall yield a rectangular dark form surrounded by a paler aura. The effect demonstrates a phenomenon, well known since the late 19th century, in which our brains consolidate many and diverse pieces of information into a greater whole. At the same time, the form seems to resist such cohesion, as if caught in the process of expanding or contracting.

Qero

Pre-Columbian Galleries, Level 2

This 17th-century drinking vessel, called qero in the Inca language Quechua, was created by Inca artists during the colonial period in Peru. The Inca often drank vast quantities of corn beer, or chicha, from these vessels during religious holidays and political gatherings. Queros were always made in matching pairs because of the reciprocal nature in which they were utilized during celebrations. In some cases, one person would furnish both vessels and the other person would supply the chicha. The Inca continued to make qeros after the Spanish invasion of South America in the 16th century because of the religious significance of such vessels to indigenous cultures.

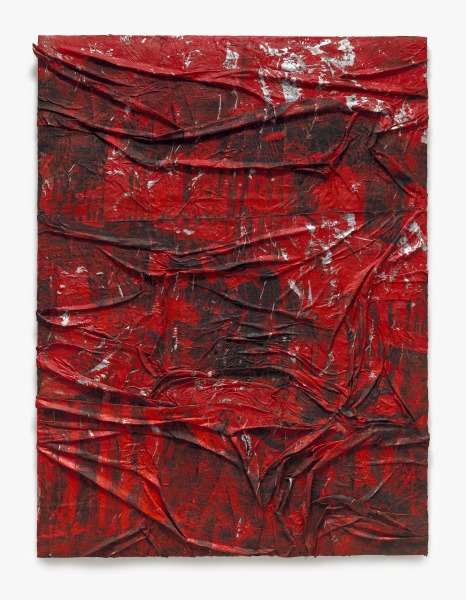

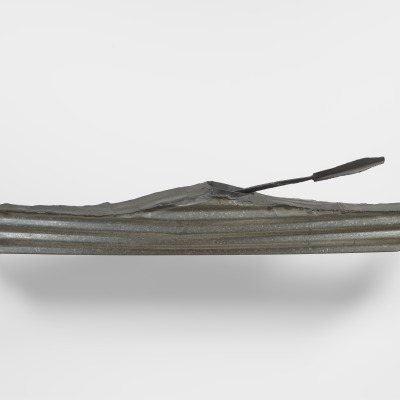

Untitled (SK-MY), Angel Otero

Otero left Puerto Rico, where he was born and raised, to study in Chicago. Now in New York, he makes paintings and sculptures that emphasize process and chance. His Skins begin with layers of oil paint applied to Plexiglas. When the paint is partially dried, Otero peels it off with homemade squeegees and blades, sliding it onto cardboard for further drying. Then he adheres the paint to canvas, where he further works the surface with brushes and knives. Oil paint came into use in the Renaissance, prized for its capacity to represent human flesh. Otero’s work takes painting well beyond representation but his thick skins drooping from canvases build on oil paint’s traditional connection to the body.

Ceremonial Poncho

Pre-Columbian Galleries, Level 2

Ceremonial weavings of the colonial and 19th-century Aymara people of Bolivia are counted as some of the finest textiles ever produced. They were sought after items throughout the Andes by both indigenous and Spanish traders. Most were produced as utilitarian articles, but some played a significant role in social, political, and religious events. This delicately constructed poncho from the Oruro region is woven from alpaca fiber, the traditional material used for these textiles. The refined weave with its complicated pattern and separate central panel was probably influenced somewhat by Hispanic examples that had migrated into the area. Given the size and complexity of the textile, this piece was almost certainly created for a gift of an important ceremonial function.

Chill, Candida Alvarez

21st Century Galleries, Level 2

“Having run away from seemingly inadequate definitions for abstract painting, I find myself immersed in a relationship that tracks, exchanges . . . there is no more picture; there is only painting.”—Candida Alvarez

Alvarez is an abstract painter whose works integrate pop art, color theory, and memory. The artist draws upon her Puerto Rican heritage through her use of complex, vibrantly layered compositions. Moving between abstract and figurative forms, she often cites pop culture, historical and modern art references, current affairs, and personal memories.

In Chill, Alvarez employs silhouettes of white and a gray against pops of bold, bright colors. The work is as much about the wintery landscape of Chicago, where the artist resides, as it is about a fascination with the aesthetics of cartoons, kitsch, and hand-crafted objects. The painting evokes the monochrome, rich with texture, yet disrupted with pops of color. Alvarez discusses the work as one in which shape and color dominate. The process of how paint is applied to the canvas becomes focal to the viewer’s eye. For the artist, notions about abstractions being devoid of figuration is debunked in this gestural wintery landscape.

Figure of a Man

Pre-Columbian Galleries, Level 2

Smiling Figures, or Sonrientes, were mass-produced by the Remojades culture (ca. 100 – 800) from the Gulf Coast area of Veracruz, Mexico. The vast quantities of these figures that remain may attest to their importance in the culture. The exaggerated gestures and clothing suggest that it is a dancing shaman or ceremonial participant. The distinctive smiling face probably indicates an altered state of consciousness, such as a trance.

How Much You Want, Arnaldo Roche-Rabell

21st Century Galleries, Level 2

Arnaldo Roche-Rabell’s work often explores issues of ambiguous and hybrid identities, including his dual connection to Puerto Rico, where he was raised and lives, and the United States, where he studied art. Process plays a central role in Roche-Rabell’s work. Here he applied gesso to paper, followed by ultramarine oil paint. Next he printed impressions of leaves in dark blue. Finally, he laid the paper over everyday items, rubbing and scraping to reveal their outlines. Pitting this direct contact with objects against their partial illegibility, he evokes contrasts of presence and absence while also suggesting cycles of human action—including accumulation, inheritance, and abandonment.

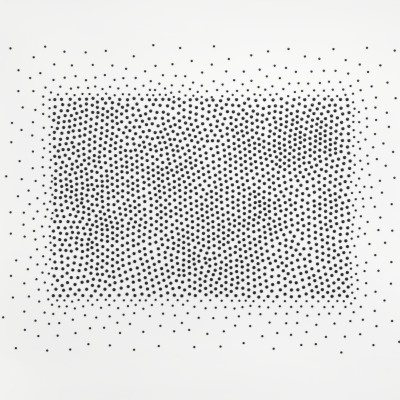

Andean Kayak: for Pablo Neruda, Rafael Ferrer

Mid to Late 20th Century Galleries, Level 2

Ferrer’s art addresses his own Puerto Rican heritage as well as each individual’s search for identity and personal meaning. In the 1970s, for an imaginary primitive culture, Ferrer developed voyage-themed images and artifacts, including maps of unknown terrain and vessels such as this kayak.

Ferrer’s use of galvanized corrugated steel—a common roofing material—connects with his memories of impoverished tropical dwellings. The work is named for the South American mountain range and the Chilean poet, diplomat, and politician who won the 1971 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Composition #76, Diego Sanchez

Diego Sanchez was born in Bogotá, Colombia, and moved to the United States with his family in 1980 where he studied painting and printmaking at VCU’s School of the Arts. This work belongs to a large group of abstract paintings that Sanchez began in 2012 after his friend and fellow artist Cindy Neuschwander encouraged him to take more risks in his paintings and experiment with abstraction. Created from a sequence of irregularly shaped vertical slats of color, which are held together and punctuated by circular elements that enliven the painting’s surface, Composition #76 enters into a fascinating dialogue with the language and history of abstract art.