LGBTQIA+ Artists at VMFA

VMFA's permanent collection proudly showcases artworks by LGBTQIA+ artists, both those who openly identify as part of the LGBTQIA+ community and those who courageously expressed their identities during times when it was not widely accepted. This resource aims to celebrate the lives, artistic endeavors, and significant contributions of these individuals. By shedding light on their stories, VMFA emphasizes the profound influence that the LGBTQIA+ community has had on shaping our collective history.

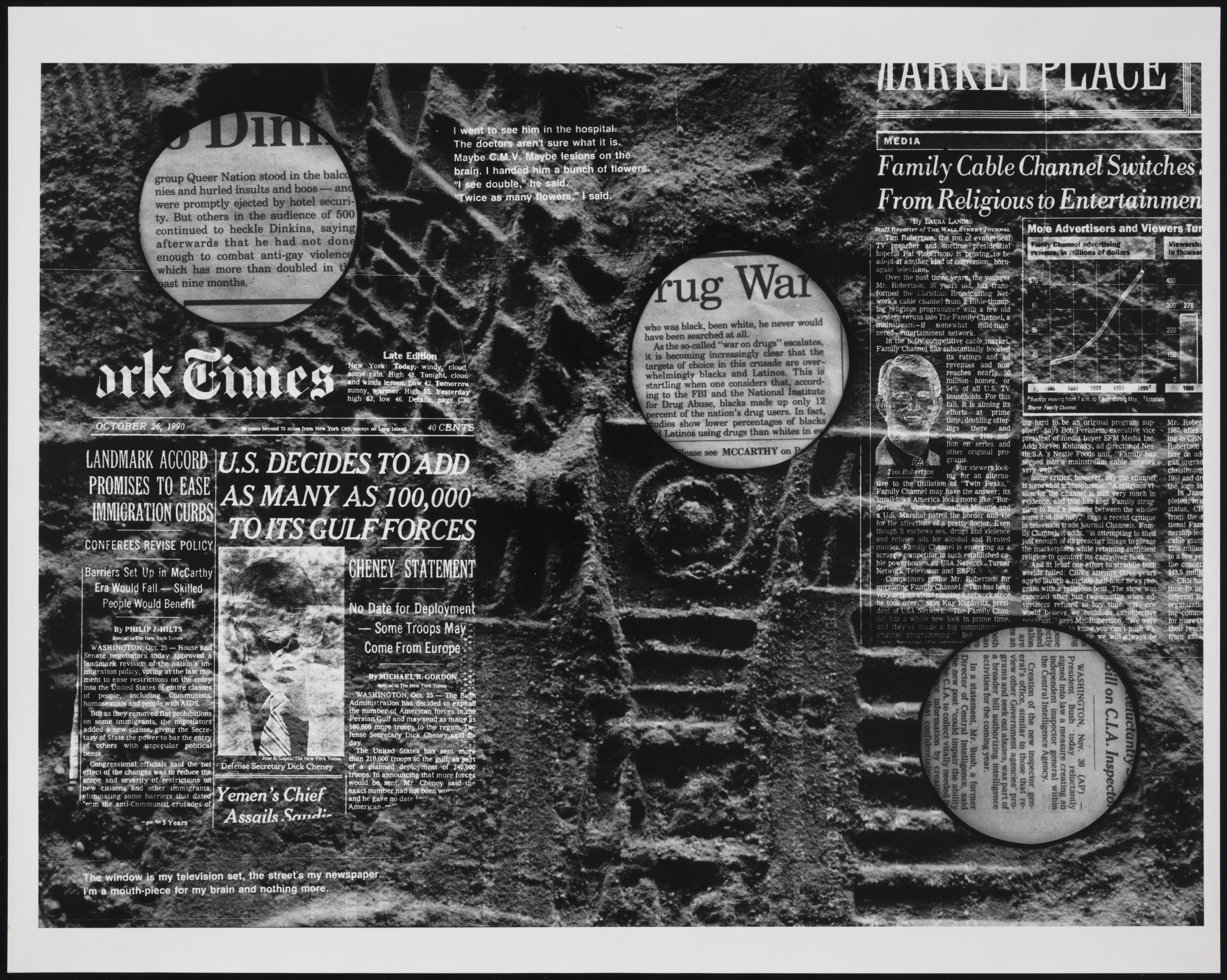

Dust Track I, David Wojnarowicz

Though he worked across a wide range of media, including painting, collage, sculpture, and film, photography was an especially powerful medium and a tool of resistance for artist David Wojnarowicz. Made in 1990, just two years before his death at age 37 from AIDS, Dust Track I alludes to the political and social turbulence of the 1980s. In this work, Wojnarowicz combined photographs he made of dust patterns etched by tire treads and boot prints with headlines and articles drawn primarily from the New York Times referencing the first Gulf War, anti-gay violence, and the rise of the religious right. Like much of Wojnarowicz’s art, Dust Track I constructs a quietly searing visual indictment of social fragmentation, institutionalized violence, homophobia and the government’s failure to address the AIDS epidemic.

Constellations (VIII), Prop Planet, Miami, Tommy Kha

In this surreal self-portrait, Tommy Kha, the child of Vietnamese and Chinese immigrants who grew up in a suburb of Memphis, Tennessee, made a cardboard cutout of himself dressed in a bedazzled suit and photographed it in a 1950s style prop room. Like Elvis, who appropriated and blended aspects of Black and white southern cultures, Kha, a queer person of color, asserts the mutability and playfulness of identity.

Two Chairs and Fireplace, Mickalene Thomas

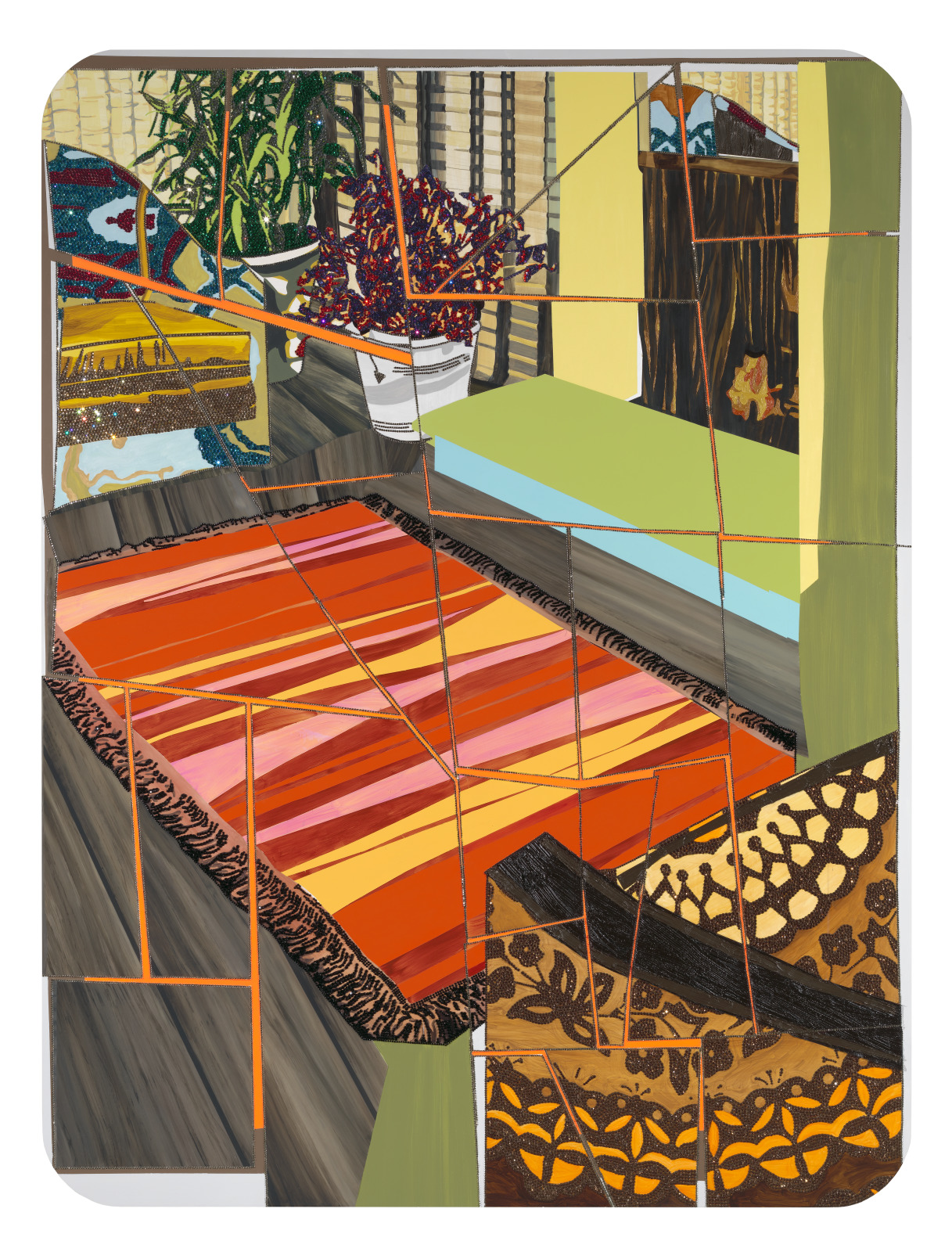

“What’s so great is that Matisse looked at Manet. And Romare Bearden looked at Matisse and Manet. And I’m looking at all three; it’s a lineage.”—Mickalene Thomas

Thomas explores traditional notions of femininity and beauty, as well as female empowerment, through paintings portraying provocative, glamorous African American women. She begins her three-part process by building sets redolent of 1970s domestic interiors, where she then poses and photographs her model. Finally, she paints the image on a much larger scale, incorporating materials such as glitter and sequins.

Thomas’s dialogue with art history is evident in this painting, which, unusually for her, presents a setting without the figure. The rich profusion of patterns plays on Henri Matisse’s paintings, while the illusion of torn and pasted fragments recalls Romare Bearden’s collages.

Franko B, London (Cross-Color Series-Scene Queens), c. 1994, Lola Flash (American, born 1959), chromogenic print. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment, 2022.93

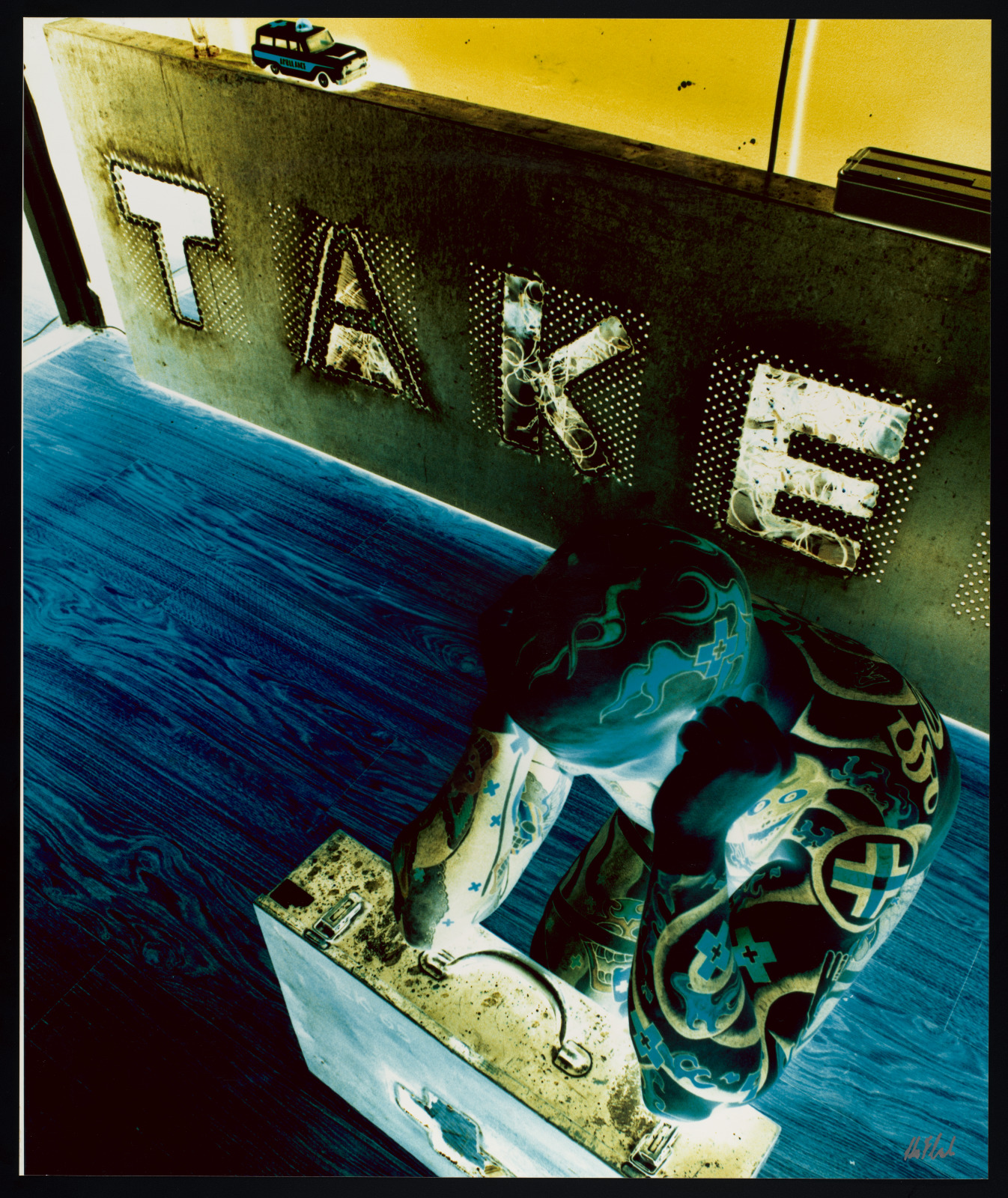

Franko B, London (Cross-Color Series-Scene Queens), Lola Flash

Starting in the 1980s, Lola Flash began experimenting with printing positive color slide transparencies onto a type of photographic paper meant for printing color negatives. This non-standard use of materials, which Flash called “cross-color,” produces an inverted color spectrum in which colors appear as their opposite: blue turns yellow/orange; red turns green, and so forth. This process enabled Flash to present the heavily tattooed London-based performance artist and gay-rights activist Franko B in eerie, dramatically unnatural shades of blue and green. Made at the height of the AIDS epidemic, Flash’s cross-color series challenges the fixity of identity, offering instead luminous and alluring visions of glowing, chimerical bodies. For Flash, who is Black and queer, disrupting conventions of color is at once an artistic and political act that undermines binary stereotypes.

Self-Portrait as a Sphinx, Sarah Bernhardt

Born Henriette-Rosine Bernard (1844-1923) in Paris, France, Sarah Bernhardt’s sixty-year career would mark her as one of the most famous actresses of all time. She broke gender barriers on stage, performing as both men and women, as well as off stage where she dressed in men’s trousers and pursued romantic relationships with both men and women.

Though she is most well known as an actress, Bernhardt was an equally talented painter and sculptor. In this self-portrait, a supernatural Bernhardt appears wearing masks of Tragedy and Comedy on each shoulder, alluding to the actress’s ability to transform into different characters. This sculptural inkwell also relates to her role as the female lead, Blanche de Chelles, in the 1880 play Le Sphinx. When the play was on tour, a cast of this work was displayed in each city where Bernhardt performed.

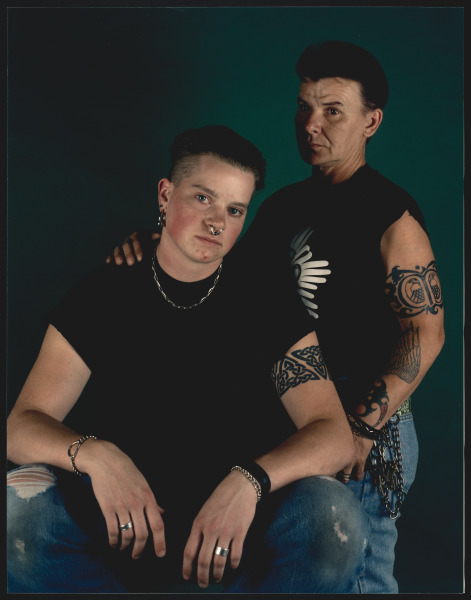

Matt and Jo, Catherine Opie

Catherine Opie reworks familiar genres, including studio portraiture, to create alluring and evocative photographs that challenge normative representations of family, place, home, love, and community. In Matt and Jo, which forms part of Opie’s 1990s series of portraits of her friends in gay, lesbian, trans and queer communities, the subtle lighting and lustrous emerald-green background recall the work of Renaissance painter Hans Holbein and, more broadly, the conventions of historic European portraits designed to command attention and respect. Opie is especially interested in how subtle details and gestures—the angle between the first and second fingers, the lightness of a hand on another’s shoulder, the set of the mouth—can convey a spectrum of emotions, in this case a mix of desire, tenderness, pride, and wariness.

King of Arms, Rashaad Newsome

Shown from below an ornate gilded urban crown draped with lush textiles, Rashaad Newsome’s video conjures the grand traditions of procession and theater. His work channels a wide range of sounds and spectacles, from Mardi Gras festivities to hip-hop music to “vogueing” (gay ballroom scene from the 1980s) exploring themes of the Black body, ornamentation, and heraldic emblems. Through a blend of conceptual and technical strategies, Newsome constructs a new cultural framework of power that promotes innovation and inclusion. King of Arms fuses the art world with the opulent ballroom scene while engaging southern traditions of procession. Newsome welcomes collaboration from a range of leaders in the worlds of art, fashion, music, and activism, providing them with a platform for creative expression. His art especially serves as a space for LGBTQIA+ voices and communities of color to shape their own representation and celebrate through pageantry and performance.

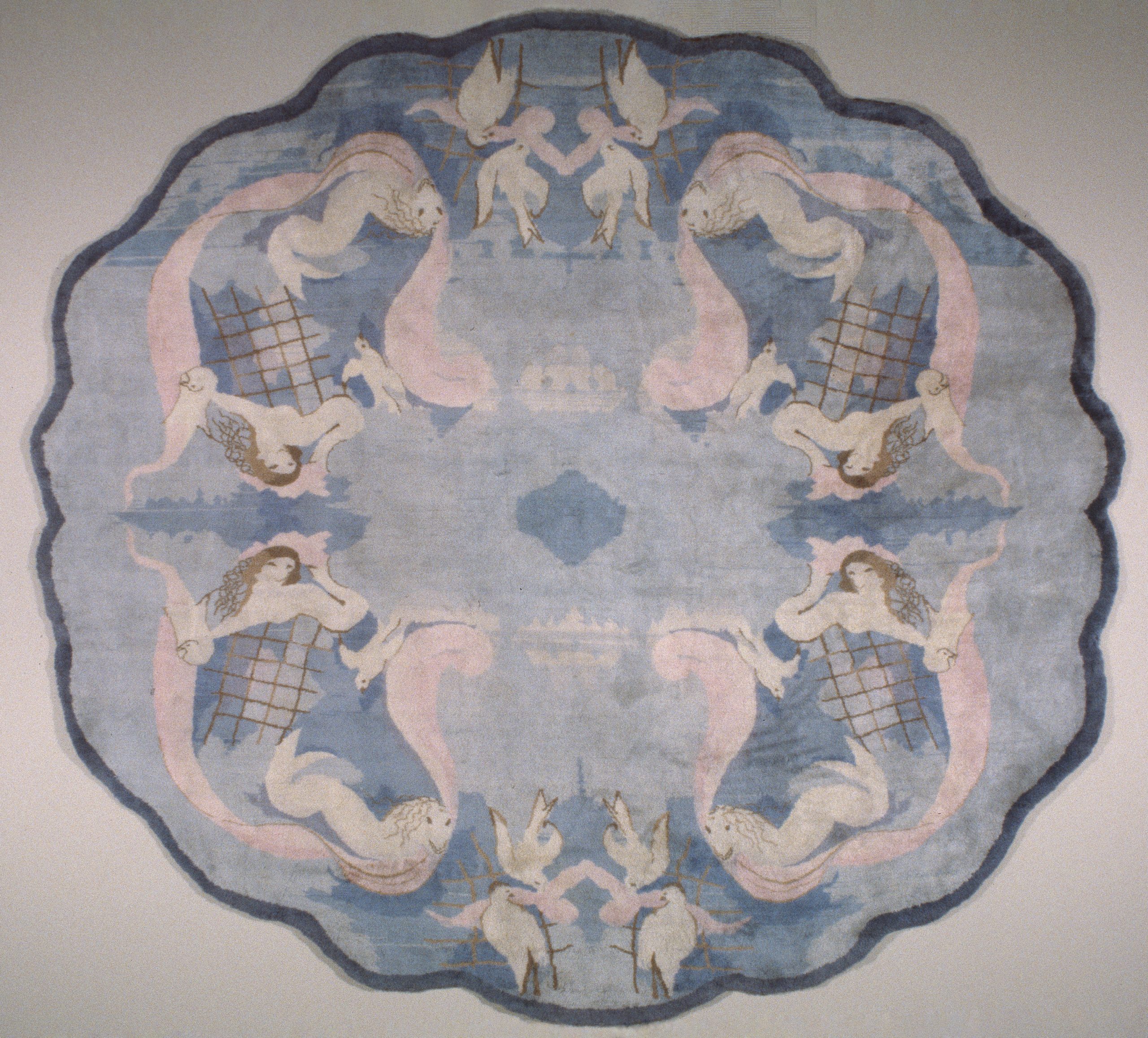

Carpet, Marie Laurencin

The French painter, printmaker, and illustrator Marie Laurencin (1883–1956) was an important figure in the Parisian avant-garde and one of the best-known women artists of her generation. The artist’s early work had strong affiliations with Cubism, but by 1923Laurencin had developed an international reputation for her paintings, watercolors, and prints of women and young girls, which collectors admired for their grace, charm, and deliberate naivete. Although critics and art historians disparaged her work during her lifetime, relegating it to the margins of modernism, recent scholars have reclaimed the sexual politics and queer identity of Laurencin’s paintings and works on paper. Her artworks, which often focused on women from Greek mythology or ancient history such as Artemis, Diana, Salome, and Sappho, connect Laurencin with the lesbian community in Paris.

TICKETED SPECIAL EXHIBITION

Frida on White Bench, New York (detail), 1939, Nickolas Muray (American, born Hungary, 1892–1965), Carbon pigment print. Private Collection ©️ Nickolas Muray Photo Archives, Licensed by Nickolas Muray Photo Archives

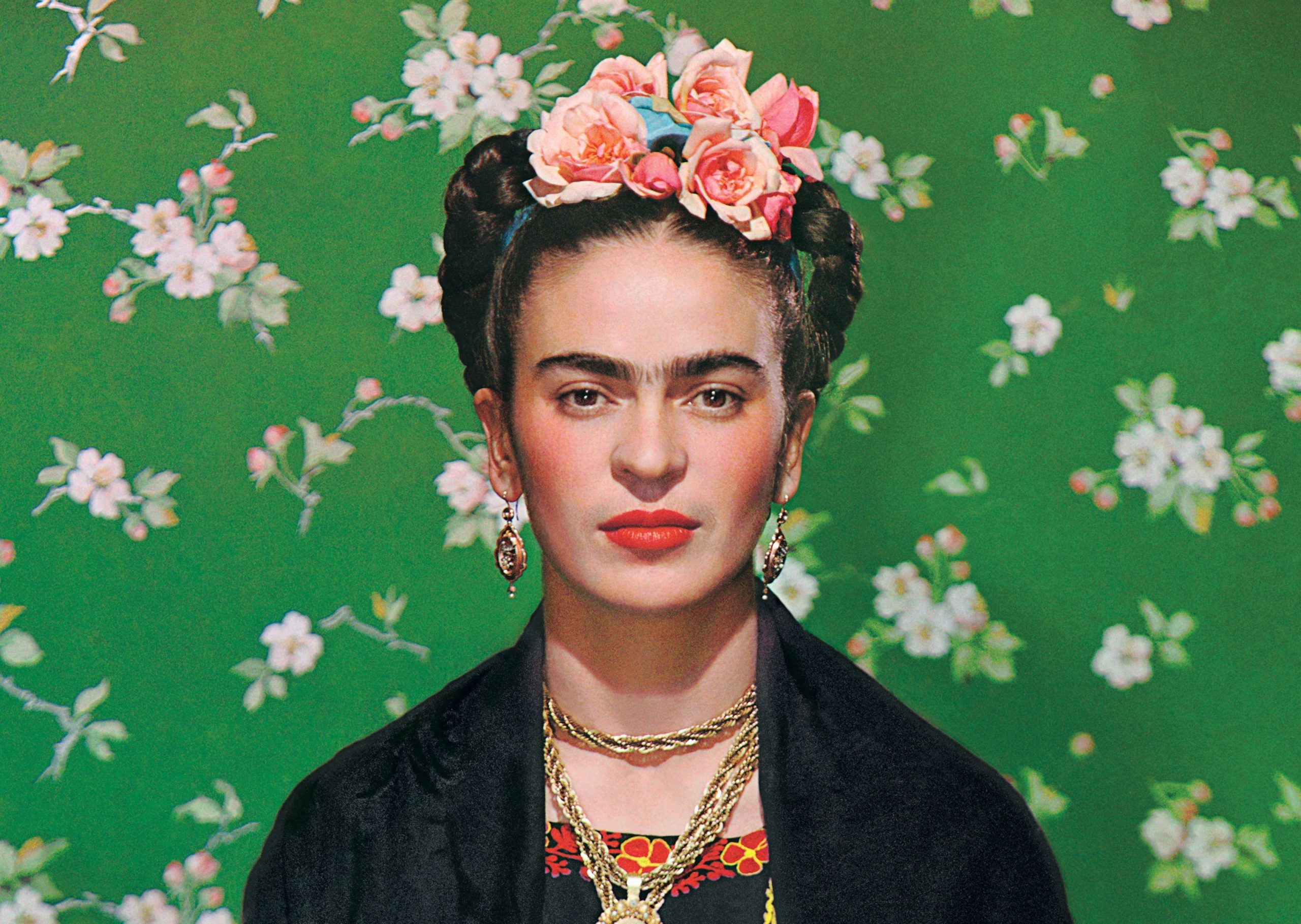

Frida: Beyond the Myth

Frida: Beyond the Myth explores the life and work of Frida Kahlo, one of the most iconic 20th-century artists. Kahlo demonstrated courage to explore individual identity in her art and in her relationships. She openly had male and female romantic partners, and she experimented with gender expression, as documented in photographs on view in the exhibition.

![Still Life, Black Mountain College [Three bottles and a glass] (Primary Title)](https://vmfa-dmz-new.piction.com/piction/ump.di?e=5534421C41B61717426727A456013ED0847A96892C452BE3B1538E320960728A&s=21&se=619188206&v=1&f=xx2013_200_v1_TF_201308_t.jpg#)

![Still Life, Black Mountain College [Three bottles and a cup] (Primary Title)](https://vmfa-dmz-new.piction.com/piction/ump.di?e=41023447702DEEECBDBF933507F6A9B69CC7A48BCA17325AF822B6F80936340D&s=21&se=619188206&v=1&f=xx2013_198_v1_TF_201308_t.jpg#)

![Still Life, Black Mountain College [Two bottles and glass] (Primary Title)](https://vmfa-dmz-new.piction.com/piction/ump.di?e=F2275883C480C5EC657893BE4F8201A851736E9A5AFEE6EB207E5C9ABFCF487C&s=21&se=619188206&v=1&f=xx2013_201_v1_TF_201308_t.jpg#)