Ancient Writing

As early civilizations developed, societies became more complicated. Record keeping and communication demanded something beyond symbols and pictures to represent the spoken word. This resource explores the early writing systems of four ancient civilizations: Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and Mesoamerica. You'll also learn about the Rosetta Stone, the 19th-century discovery that gave scholars the key that unlocked the language of ancient Egypt.

How Ancient Writing Began… and Ended

As early civilizations developed, societies became more complicated. Record keeping and communication demanded something beyond symbols and pictures to represent the spoken word. This gallery explores the early writing systems of four ancient civilizations: Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and Mesoamerica. Here you’ll also learn about the Rosetta Stone, the 19th-century discovery that gave scholars the key that unlocked the language of ancient Egypt.

Why were writing systems developed?

- Communication – Sounds and speech needed to be visually represented.

- Correspondence – There was a desire to send notes, letters, and instructions.

- Recording – Bookkeeping tasks became important for counting crops, paying workers’ rations, and collecting taxes.

- Preservation – Personal stories, rituals, religious texts, hymns, literature, and history all needed to be recorded.

Why did some writing systems disappear?

- Change – Corresponding cultures died out or were absorbed by others.

- Innovation – Newer, simpler systems replaced older systems.

- Conquest – Invaders or new rulers imposed their own writing systems.

- New Beginnings – New ways of writing developed with new belief systems.

China

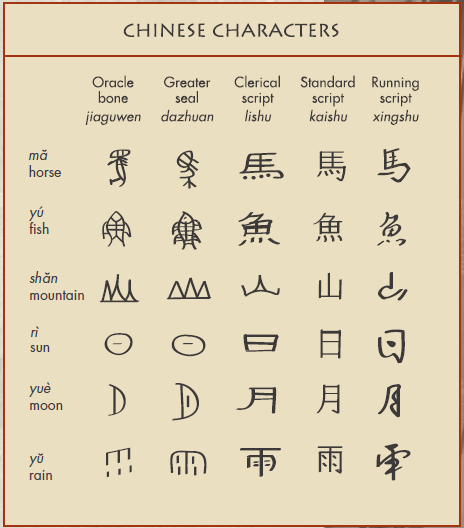

Can you note the changes made from bone to seal and seal to script?

Who? Chinese

When? Late Shang dynasty, 1300-1100 BC

Where? The earliest Chinese writing was found in archaeological excavations in the modern Xiantun village at Anyang in Henan province.

Why? The Chinese needed a writing system for recording royal divination performances during the Shang dynasty, as well as for documenting events and activities, including hunting, warfare, the weather, and the selection of lucky days for ceremonies.

What? Displaying over 4,500 characters and symbols, ancient Chinese oracle bones ,which were used for predicting the future, are the earliest evidence of Chinese writing. Today, with over 40,000 characters, the Chinese language has various levels of literacy. You can read Chinese newspapers and magazines by knowing only about 3,000 characters.

How? Characters incised onto turtle shells, ox bones, caste in bronze vessels

System? Chinese is the oldest continuously used writing system in the world. Chinese characters are monosyllabic , and each character has a meaning. Ancient Chinese is written from top to bottom and right to left.

Chinese characters are known as hanzi. The characters were originally pictures of people, animals, or things, but over centuries, hanzi have become increasingly stylized and no longer pictorially representative. Many characters have since been combined with others to create new ones. Until the early 20th century, classical Chinese, wenyan, was the main form of writing in China.

Egypt

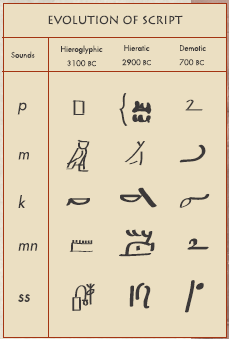

How have the symbols become more simplistic?

Who? Egyptians

When? 3100 BC – 400 AD

Where? Earliest Egyptian writing was found in Tomb U-j of Umm el’Qa’ab, at the site of Abydos in Upper Egypt, Africa.

Why? Egyptians needed a writing system to handle a growing and increasingly complex society and to gain administrative control (e.g. to record deliveries, materials, labor, and property).

What?

The word hieroglyph comes from the Greek hieros (sacred) and glyphos (words or signs). The ancient Egyptians called their writing mdju netjer (words of the gods).

How?

Carvings onto small bone, ivory, clay, or stone; ink on papyrus; painted walls.

System?

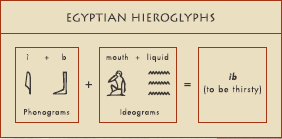

Egyptian glyphs are divided into two groups: phonograms, which represent sounds, and ideograms, which represent objects or ideas. The Egyptians constructed words by using a combination of glyphs. The ancient Egyptian writing system had 700-800 glypghs. Only royalty, scribes, priests, and government officials could use hieroglyphic writing.

Hieroglyphs are time consuming to produce and require a great deal of skill and knowledge, so it is only in the early period that we find hieroglyphs written on every type of material and for every purpose. By the first dynasty (around 2900 BC), Egyptians created a simplified cursive script known as hieratic. During the 7th century BC, they began using demotic (a cursive script even more simplified than hieratic) for business and literary texts.

Can you read the equation?

Mesoamerica

Do you see any familiar symbols?

Who? Maya (although hieroglyphs have been found in sites occupied by pre-Mayan cultures such as the Olmec)

When? 300 BC – 1650 AD

Where? The earliest Maya writing was found in the area now known as southeastern Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and Belize.

Why? The Maya people needed a writing system to meet the demands of regional population growth and to record events in the lives of elite, ceremonial functions, and economic transactions.

What? Ancient Maya glyphs are a complex, visually striking writing system with hundreds of unique signs or glyphs in the form of humans, animals, supernaturals, objects, numbers, and abstract designs.

How? Carved in jade, stone, bone, wood, ceramics and shell; written on bark

System? The Maya script is logosyllabic combining about 550 logograms (which represent whole words) and 150 syllabograms (which represent syllables). There were also about one hundred glyphs representing place names and the names of gods. About three hundred glyphs were commonly used. Maya inscriptions were most often written in columns two-gylphs wide, with each column read left to right, top to bottom. The calligraphic styles and pictorial complexity of Maya glyphs are like no other writing system.

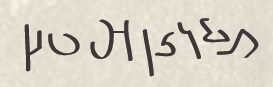

Mesopotamia

Can you trace the similarities in the characters?

Who? City-states and kingdoms of Mesopotamia

When? 3500 BC – 500 AD

Where? Earliest Sumerian writing was found in the temple precinct Eanna, the city-state of Uruk, located in southern Babylonia in present-day Iraq.

Why? Sumerians needed a writing system because of the sudden expansion of Babylonian city-states, socio-cultural complexity of administrative tasks, and scribal training.

What? Cuneiform is the writing system developed by Sumerians. (Cuneiform comes from two Latin words: cuneus, which means “wedge,” and forma, which means “shape.”)

How? Writing with reeds onto wet clay

System? Before cuneiform, and as early as 8000 BC, people of Mesopotamia used logograms (pictures that represent words), but a recognizable system of logograms and phonetic script did not develop until about 3200-3100 BC.

Because drawing on clay is difficult, the Mesopotamians eventually reduced pictograms into cuneiform , a series of wedge-shaped signs that they pressed into clay with a reed stylus. Cuneiform came to function both phonetically (representing a sound) and semantically (symbolizing an object or concept) rather than only pictorially.

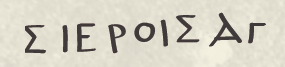

The Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone features script in three different writing systems: Greek, demotic, and hieroglyphic. In 1799, during Napoleon’s campaign to conquer Egypt, French soldiers discovered the stone near the village of Rosetta. Linguists later used their knowledge of Greek to decode the demotic and hieroglyphic scripts. By identifying certain ancient Egyptian words, researchers were able to translate the Stone’s message: a decree that says priests of a temple in Memphis support ht reign of thirteen-year old Ptolemy V, on the first anniversary of his coronation.

The Rosetta Stone’s three scripts appear in this order:

Hieroglyphic script: ancient Egyptian script, used by Egyptian kings and priests for formal use.

Demotic script: ancient Egyptian script used for everyday writing.

Ancient Greek: official language of the Ptolemaic rulers and the common language of the Mediterranean world at this time.

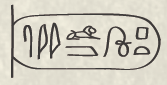

By analyzing the Rosetta Stone and other texts, the young French scholar Jean-Francois Champollion (1790-1832) made a significant advance in understanding ancient Egyptian writing when he pieced together hieroglyphs used to write the names of non-Egyptian rulers. These names could be recognized because, following Egyptian conventions, they were written in a cartouche, and oval-shaped border used only for the names of very important people. (The cartouches seen on the Rosetta Stone enclose the name Ptolemy.)

Following France’s defeat in Egypt, the Rosetta Stone was surrendered to the British authorities and given to King George III, who gave it to the British Museum of Art in London. The Rosetta Stone, made in 196 BC (Egypt’s Ptolemaic Period), has been on display in London for more than two hundred years.

The Rosetta Stone, The British Museum

Related Objects in VMFA's Collection

Funerary Vessel, 600-800 AD Terracotta with polychrome pigments Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund

Maya (Mexico or Guatemala)

The Maya people inhabited southern Mexico, Guatemala, and northern Belize, and parts of Honduras and El Salvador. Between 250 BC and 900 AD, they established a com-plex system of writing and build majestic temple pyramids and palaces in urban centers, which still can be seen in the ancient ruins of Tikal and Palenque. On ceramics, glyphs may describe the function and contents of the pot, and sometimes identify the owner or the scribe who painted it, although this vase does not name the exact artist. The scene unfolding around this vessel depicts a ritual in a palace setting. The glyphs name the main characters who sit on either side of a large basket: Lord Hok’in bat (seated on the throne) and Kan Xib Ahaw (seated opposite him). A third figure sits behind them, and a forth removes an embroidered, fringed textile from the large block.

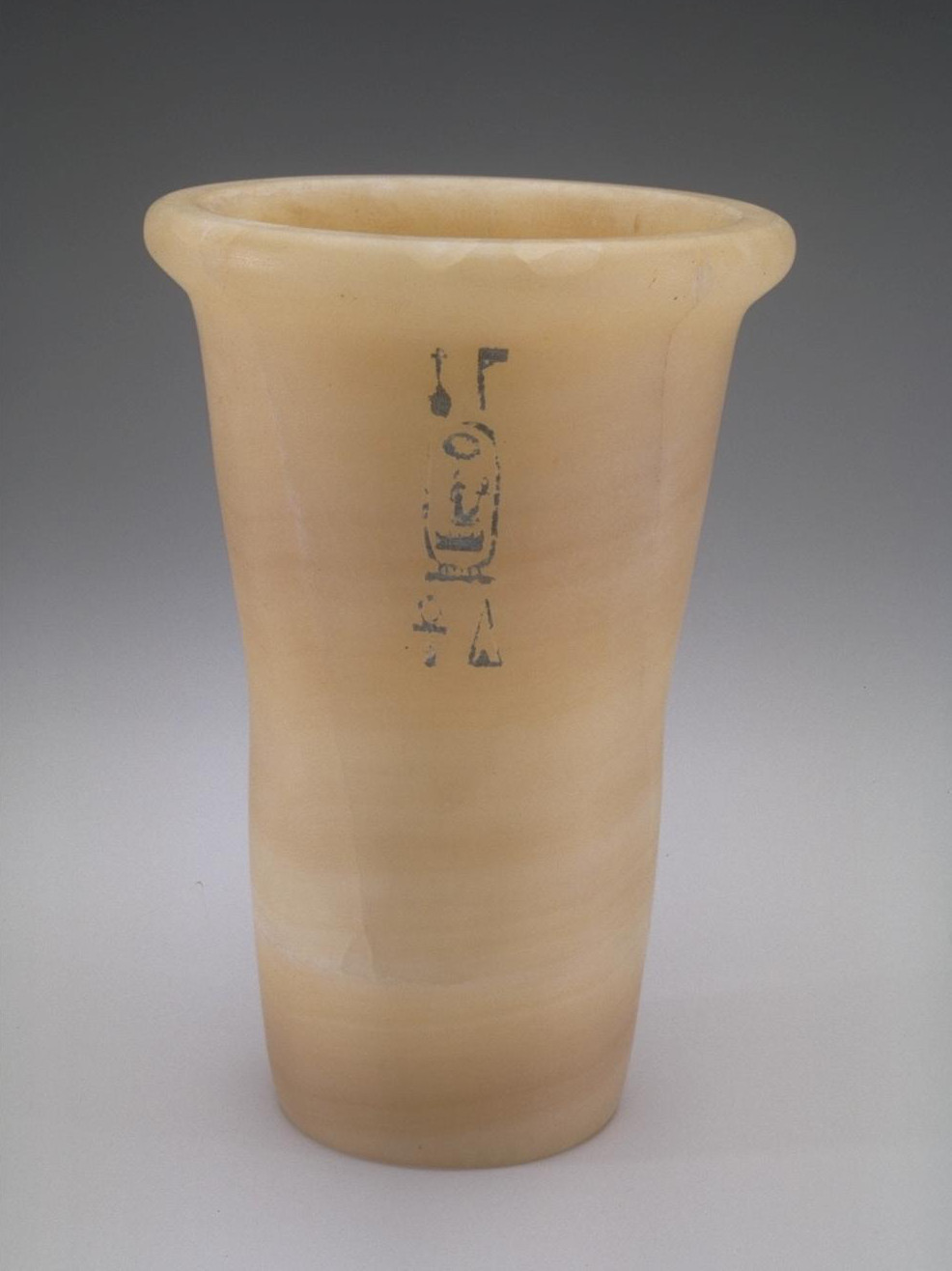

Vase, 1294-1279 BC

Alabaster

Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Fund

Egyptian, Dynasty 19

This vase bears the name of the Seti I in a cartouche, an oval frame surrounding the royal name. Seti I was the son of Ramses I, the founder of Dynasty 19, and undertook a number of military campaigns in the Levant as well as a number of building projects, including his mortuary temple at Abydos. The vase is made of alabaster, a popular and common stone in ancient Egypt. The vessels’ walls are extremely thin, indicating the great skill of the stone carver.

Canopic Jar, ca. 712-332 BC

Alabaster

Gift of Randall Worthington

Egyptian, Late Period

As part of the mummification process, the internal organs of the deceased were removed, preserved, and for much of Egyptian history, placed in vessels, which are today called canopic jars. Beginning in the New Kingdom, the lids of the vessels were designed as the heads of animals, protectors of the organs inside. Each animal was associated with one of the four sons of Horus. Imsety, who was represented by a human head, was usually the guardian of the liver.