By Dr. John Edwin Mason

Author’s Note: This blog post draws heavily on an essay, also called “The Sounds They Saw: Kamoinge and Jazz,” that I wrote for the exhibition catalogue Working Together: Louis Draper and the Kamoinge Workshop. I’m grateful to the photographer Herb Robinson, a member of Kamoinge, for selecting the music that accompanies this blog post.

One of the things about the founding members, particularly, is that pretty much all of us were jazz fanatics.

-Shawn Walker

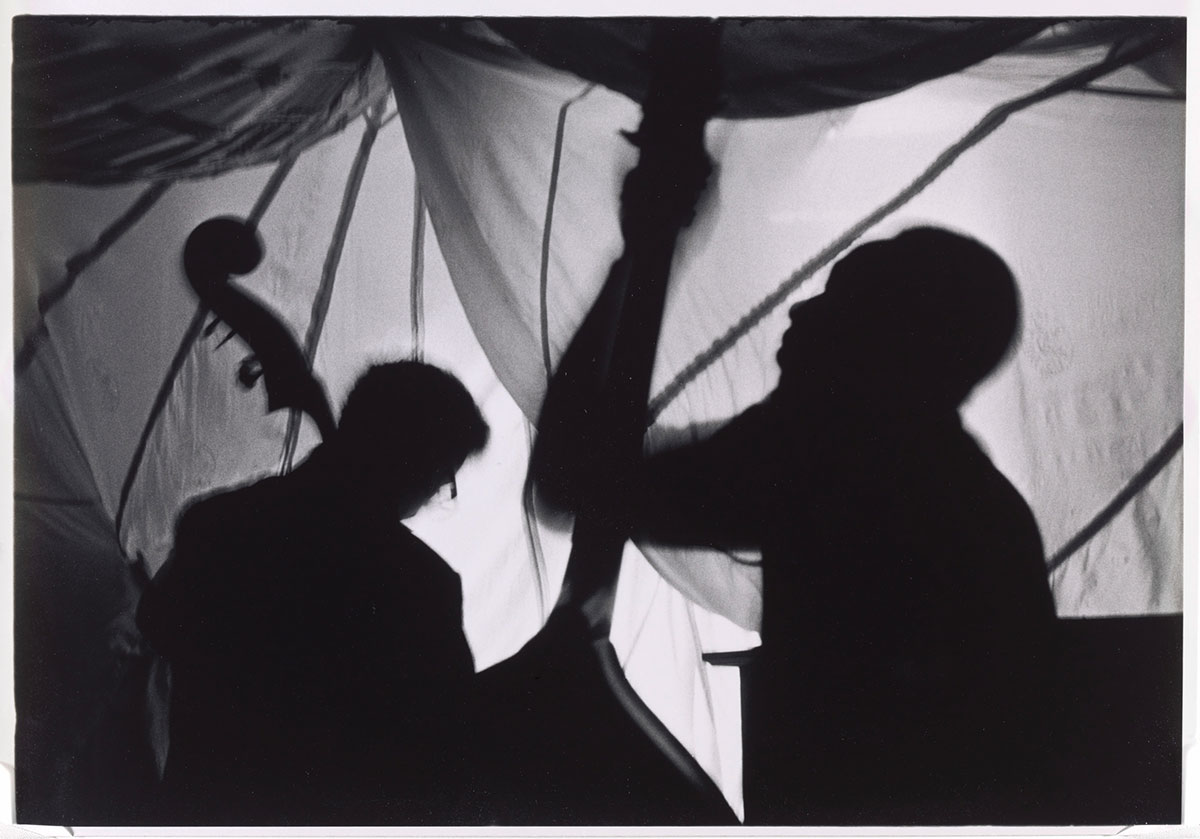

Two Bass Hit, Lower East Side, 1972, Beuford Smith (American, born 1941), gelatin silver print.

Two Bass Hit, Lower East Side, 1972, Beuford Smith (American, born 1941), gelatin silver print.

Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment, 2017.36

Sometime in the early 1980s, Louis Draper, the Kamoinge Workshop’s most prolific chronicler, jotted down some notes about jazz. They fill ten pages of a cheap, spiral-bound notebook—the sort that high school and college students use. Draper kept it when he was working as a production assistant on the film Losing Ground. Technical details about the movie compete for space with notes about “Bird” and “Prez,” the jazz world’s nicknames for the already legendary saxophonists Charlie Parker and Lester Young. Although Draper organized the notes in a coherent chronological order, identifying key moments in the lives of the two musicians, the notes’ irregular spacing on the page and the nonchalance of Draper’s handwriting suggest the improvisational freedom of a jazz solo.

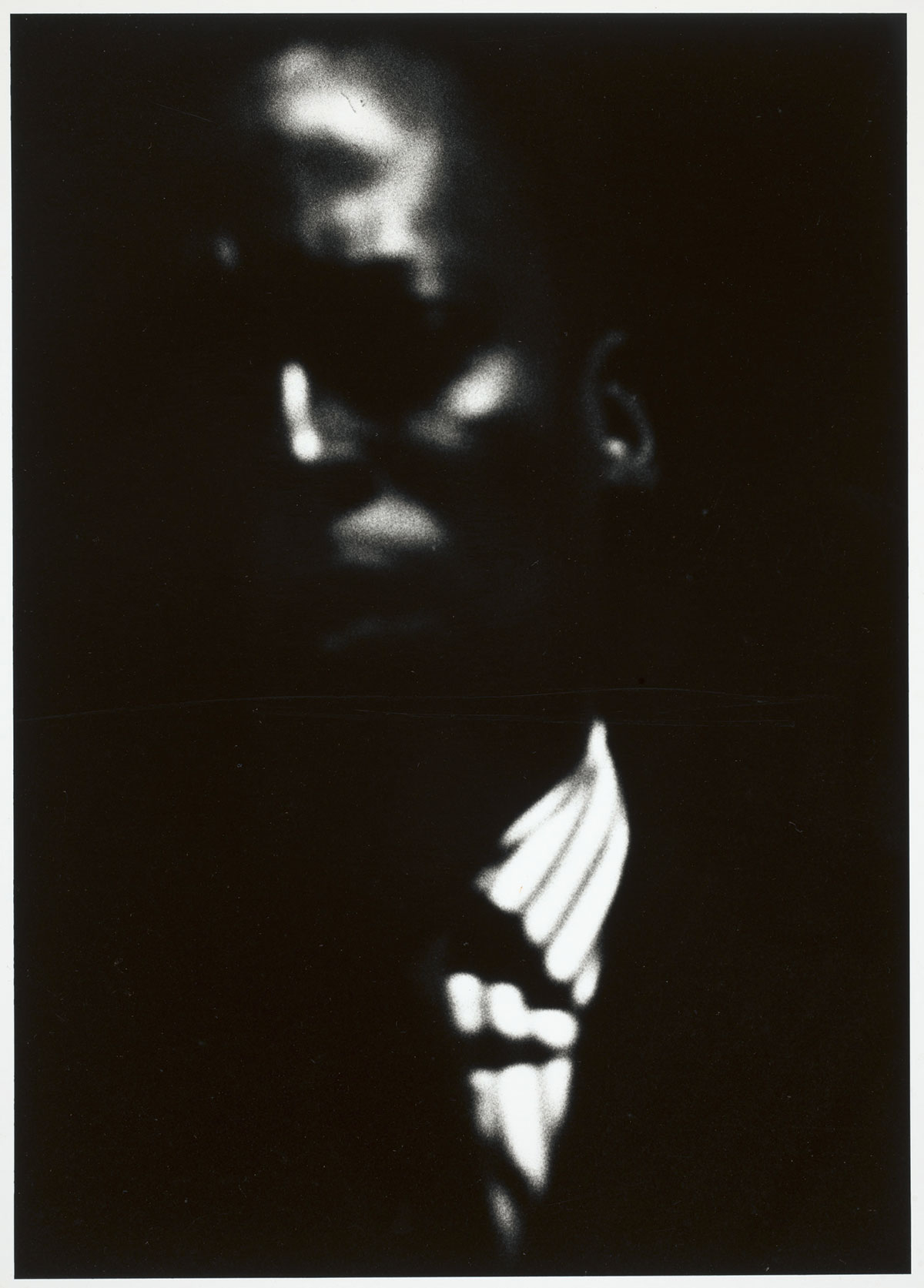

Miles Davis at the Village Vanguard, 1961, Herb Robinson (American, birthdate unknown), gelatin silver print.

Miles Davis at the Village Vanguard, 1961, Herb Robinson (American, birthdate unknown), gelatin silver print.

Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment, 2017.36

Listen to Miles Davis, “On Green Dolphin Street.”

It is not clear why Draper made the notes or what he intended to do with them. It is probably not a coincidence, however, that he kept the notebook while he was taking courses in filmmaking and screenwriting. Was he working on a screenplay? If so, the rollcall of nightclubs and recording sessions in the notebook could have been a list of potential scenes in a movie. He might have been seeing the sound of jazz with his mind’s eye and thinking about ways to show it to an audience. Whatever the notebook’s purpose, one thing is clear: it grew out of his lifelong love for the music.

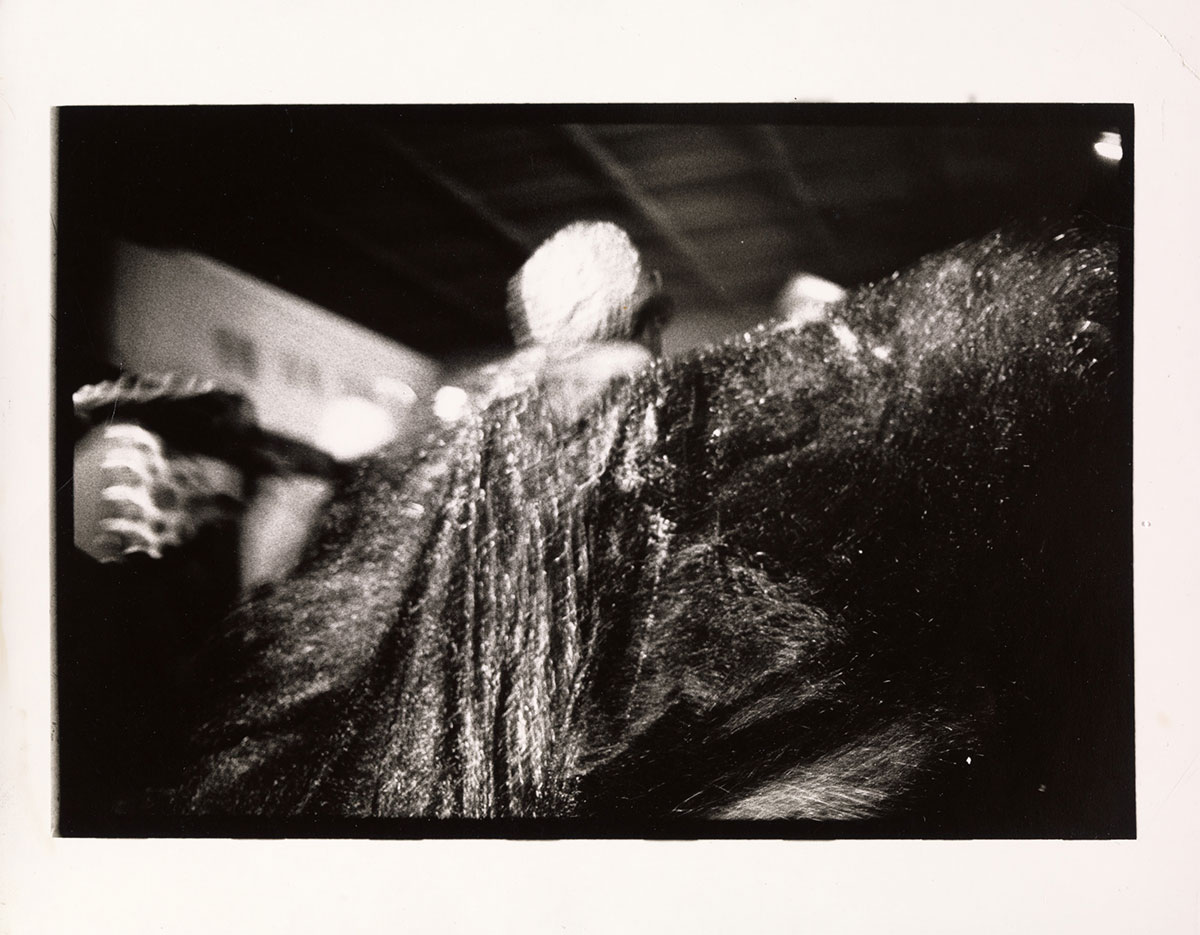

Sun Ra space I, New York City, NY, ca. 1978, Ming Smith (American, birthdate unknown), gelatin silver print.

Sun Ra space I, New York City, NY, ca. 1978, Ming Smith (American, birthdate unknown), gelatin silver print.

Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 2016.244

Draper shared that love with his brothers and sisters in Kamoinge. From the very beginning, jazz was the workshop’s soundtrack. It was much more than mere background music at meetings; it was also one of the bonds that held the organization together. Kamoinge founding member Shawn Walker says that “All of us were into the music, and I think that’s what really made us so tight. It’s because all of us loved jazz.” They were, in his words, “jazz fanatics.” They were also photographers who found both inspiration and subject matter in the music. Cameras in hand, they devised ways to see that which cannot be seen, to make something as intangible as a sound wave as substantial as a photographic print.

Listen to The Oscar Peterson Trio with Milt Jackson, “Dream of You.”

For Kamoinge’s members, jazz musicians were not merely icons of style, as they often were for jazz lovers, or alluring subject matter, as they were for many photographers. They were also paragons of artistic and racial achievement. Daniel Dawson explains that

Our highest models of artistic creation were the musicians. They weren’t necessarily the visual artists. We were all influenced by [photographers such as] Eugene Smith and Cartier-Bresson and Roy DeCarava and Gordon Parks. But our strongest influences were Miles Davis and Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk and Charlie Parker and John Coltrane. The highest standards of excellence that we had in the black community were the musicians.

Shawn Walker agrees, saying that “[t]he one thing I understood from jazz was how good you could be.”

Whenever you think you’ve reached a plateau, go to a set and you realize, Oh, ****, did he really play that? Did he do that? I didn’t know you could do that on a horn. . . . You’ve got to be awed by that. I want to do it with my camera. Jazz musicians were the vanguard of our culture.

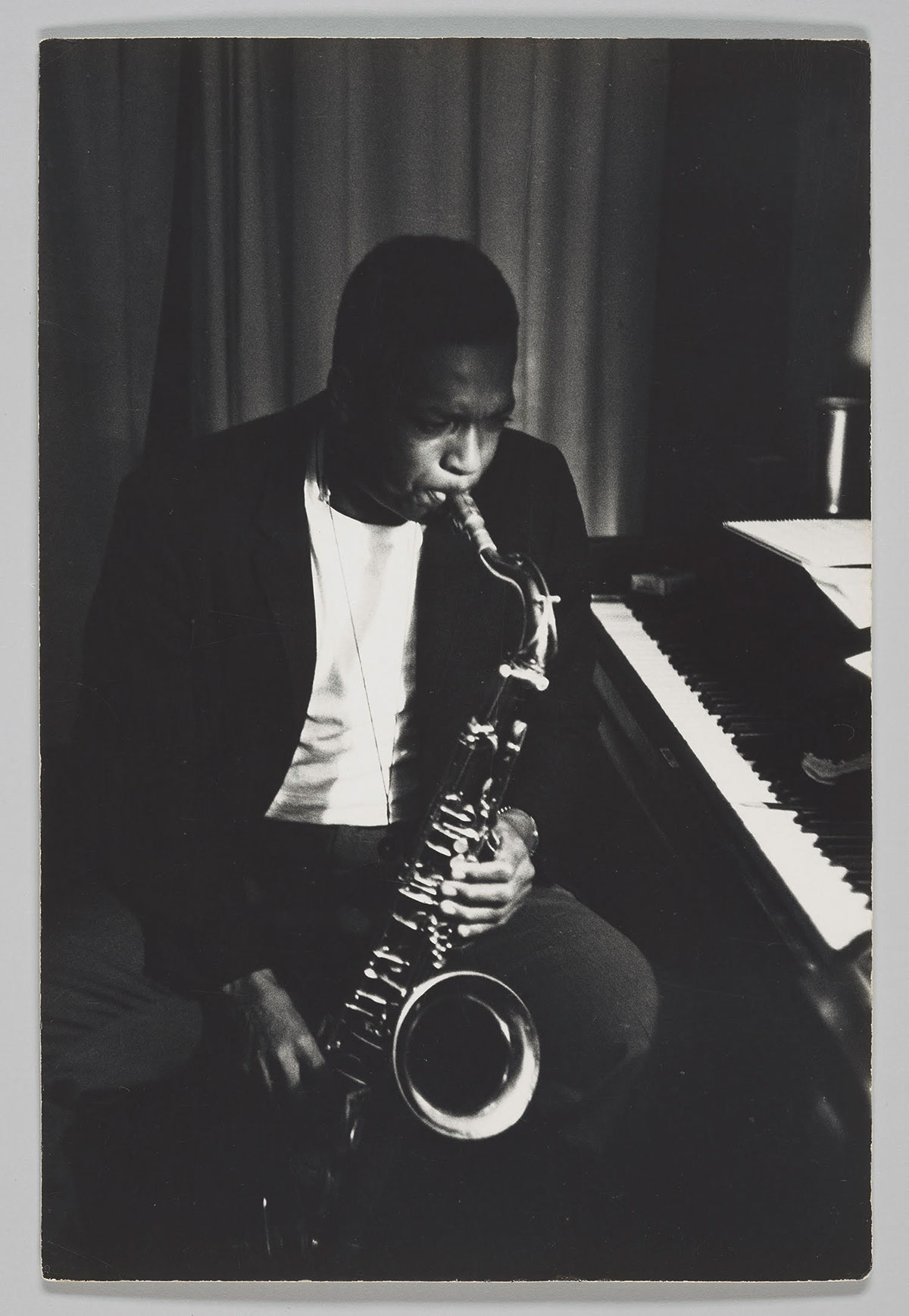

John Coltrane, 1960–67 Louis Draper (American, 1935–2002), gelatin silver print.

John Coltrane, 1960–67 Louis Draper (American, 1935–2002), gelatin silver print.

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Nell Draper-Winston, 2013.66.1

Listen to The John Coltrane Quartet, “I Wish I Knew.”

Although jazz is an essential part of the artistic practice of most of Kamoinge’s members, the approaches that they take to it are as diverse as the music itself. Ming Smith, who joined the organization in 1972, came to jazz later in life than most of the other members, but it became crucial to her personally and professionally. For several years, she was married to David Murray, a prominent saxophonist. She says that “[t]he style of my photography” came to be “informed by the music” that he and other jazz musicians played. The improvisation that is inherent in jazz showed her “a way of expressing [myself], whatever that might be.” Dawson, who also joined Kamoinge in 1972, but whose involvement in jazz and photography goes back much farther, argues that the relationship between music and the visual arts goes beyond the inspiration artists find in it. “They’re inseparable,” he says. Dawson traces this bond back to an African conception of art. “Because if you look at African American art or any kind of African art, it’s holistic. . . . [T]he visual art is inseparable from the musical art. . . . And even though we’ve lost the African linguistic elements that tie that together, we haven’t lost that in our lives.”

Okra Orchestra, Brooklyn, NY Rehearsal, 1978, Anthony Barboza (American, born 1944), gelatin silver print.

Okra Orchestra, Brooklyn, NY Rehearsal, 1978, Anthony Barboza (American, born 1944), gelatin silver print.

Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment, 2019.10

Listen to Dexter Gordon Quintet, “I Was Doin’ Allright.”

Jazz showed the members of Kamoinge how to make art without restrictions. They became aesthetic, intellectual, and even geographic explorers. Their art was improvisational and dynamic, constantly in motion, continually evolving. They were in conversation with the artistic and political currents that swirled around them. They created art that embodied racial pride and self-assertion simultaneously, and, like jazz, transcended boundaries of genre and race. Through jazz, they found a kind of freedom.

Dr. John Edwin Mason is associate professor for the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, where he teaches African history and the history of photography. He is now working on Gordon Parks: American Photographer, a critical study of the photo-essays on race and social justice that Parks produced for Life magazine.