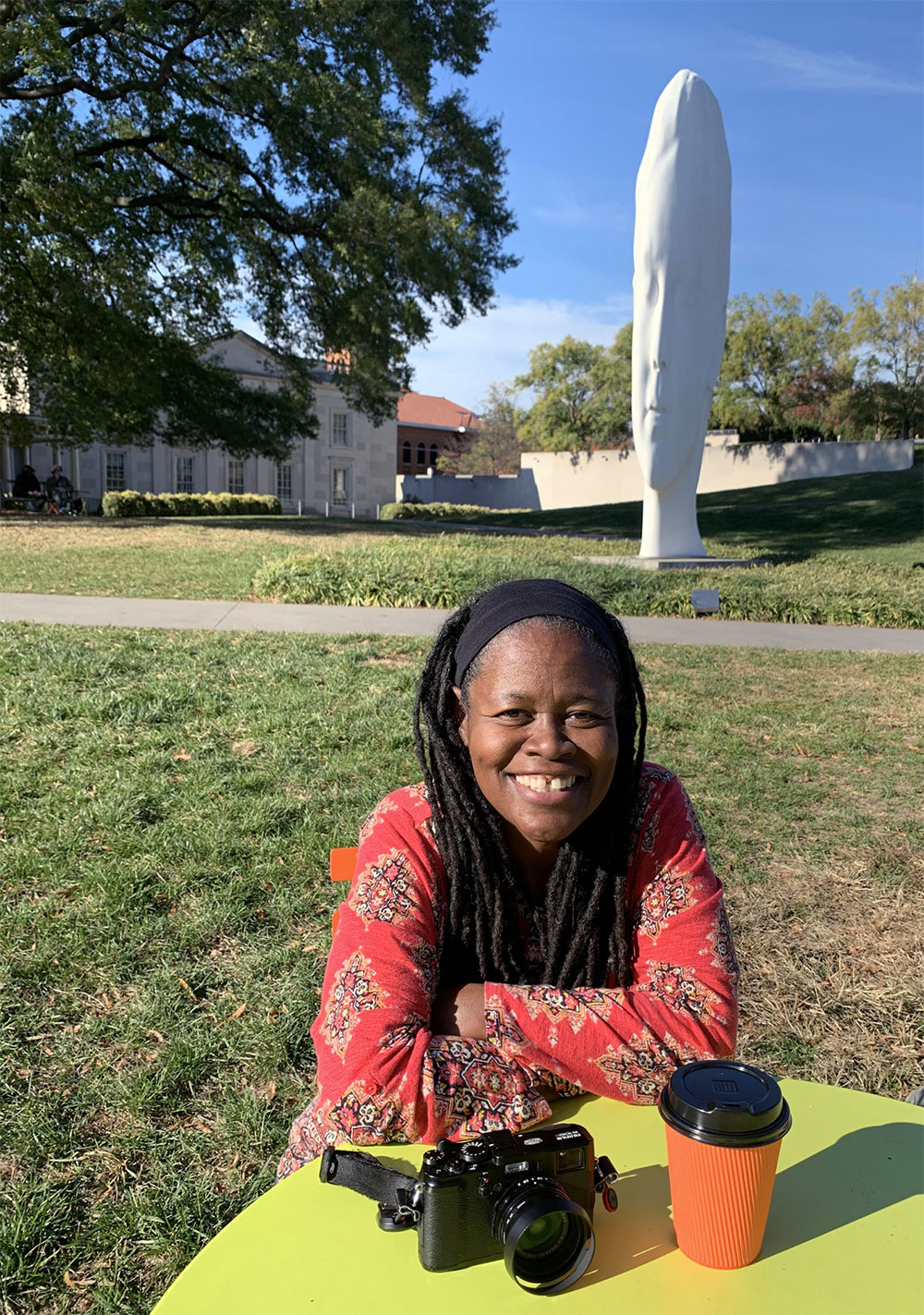

Sandra Sellars is an assistant photographer at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and VMFA’s Louis Draper Archive photographer. Sellars is also an award-winning photojournalist for the Richmond Free Press—a Black–owned and operated newspaper. She will be a featured presenter in VMFA’s free seven-part virtual symposium titled The Kamoinge Workshop: Collaboration, Community, and Photography, which began Sep 3, 2020.

Sandra Sellars is an assistant photographer at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and VMFA’s Louis Draper Archive photographer. Sellars is also an award-winning photojournalist for the Richmond Free Press—a Black–owned and operated newspaper. She will be a featured presenter in VMFA’s free seven-part virtual symposium titled The Kamoinge Workshop: Collaboration, Community, and Photography, which began Sep 3, 2020.

Here, Sellars shares her personal reflections and the photographs she took (unless otherwise noted) of the artists, archives, and the exhibition Working Together: Louis Draper and the Kamoinge Workshop.

Personal Reflections: Delving into Draper

I am hard pressed to find a photograph in the Working Together: Louis Draper and the Kamoinge Workshop exhibition about which I don’t say, “I love this image.” After working on the Louis H. Draper Archive for nearly two years, I am awestruck as to how each of the Kamoinge Workshop photographers put themselves in a position to see and seize the moment— technically, emotionally, and uniquely.

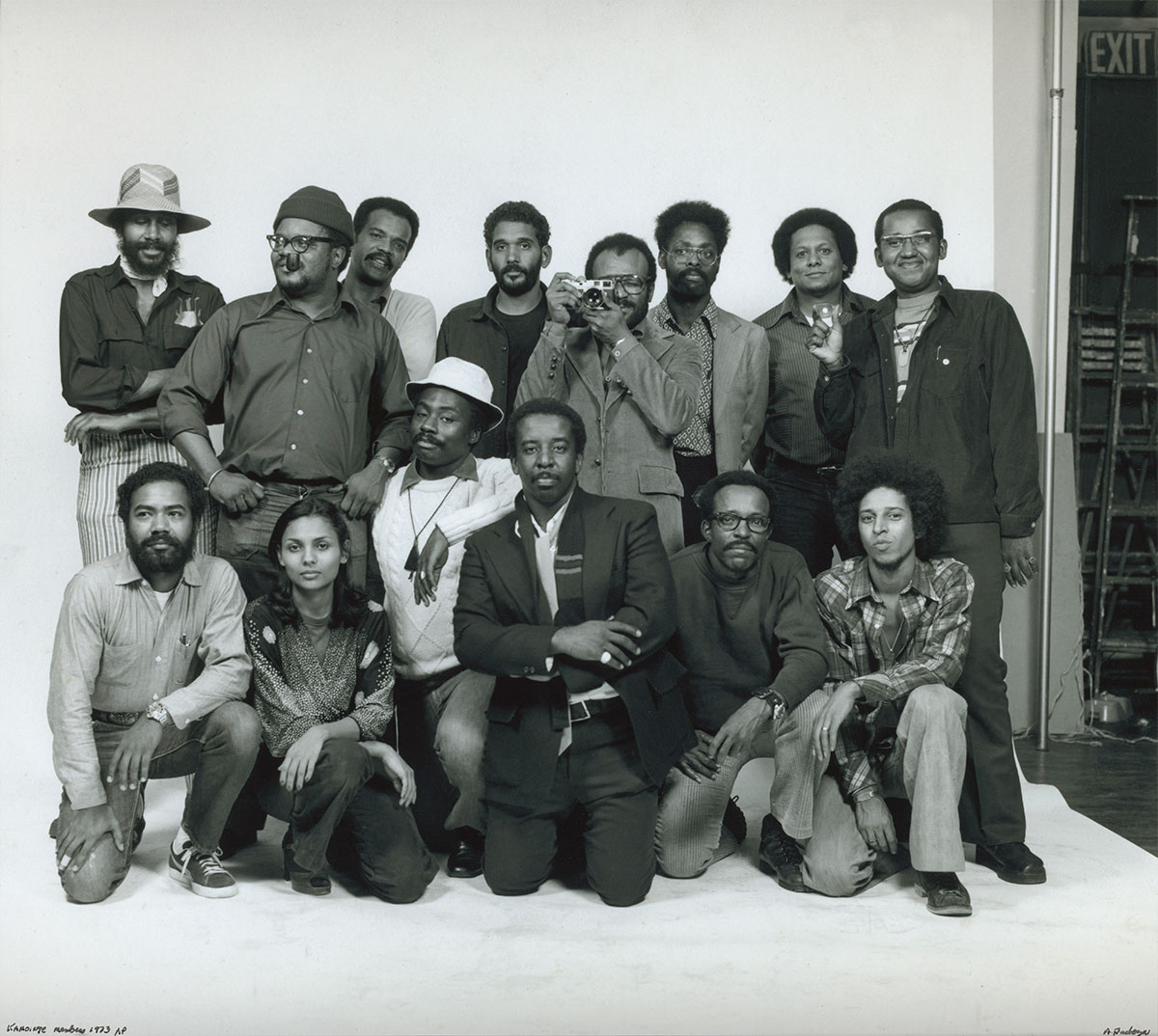

Kamoinge Group Portrait (detail), 1973, Anthony Barboza (American, born 1944), Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Courtesy Eric and Jeanette Lipman Fund, 2019.249 © Anthony Barboza photog

Kamoinge Group Portrait (detail), 1973, Anthony Barboza (American, born 1944), Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Courtesy Eric and Jeanette Lipman Fund, 2019.249 © Anthony Barboza photog

Opening Reception for Working Together: Louis Draper and the Kamoinge Workshop, January 29, 2020. Top row, left to right: James Mannas, Herb Robinson, C. Daniel Dawson, Beuford Smith. Bottom row, left to right: Herb Randall, Shawn Walker, Anthony Barboza, Adger Cowans. Photograph by David Stover, © VMFA

Opening Reception for Working Together: Louis Draper and the Kamoinge Workshop, January 29, 2020. Top row, left to right: James Mannas, Herb Robinson, C. Daniel Dawson, Beuford Smith. Bottom row, left to right: Herb Randall, Shawn Walker, Anthony Barboza, Adger Cowans. Photograph by David Stover, © VMFA

As the photographic archivist, very early in the project, I eagerly looked forward to this exhibition. My excitement grew throughout the days leading up to the opening, additionally fueled by the curator’s invitations to see newly acquired pieces and to travel to the sites of artist interviews. My days were busy, but the payoff was always just on the horizon.

Working Together: Louis Draper and the Kamoinge Workshop is a prominent acknowledgment of African American artistry in photography and beautifully presents the cultural impact of this work. Removing “un” as a descriptor is a powerful act—untold, unseen, unknown, and unsung are terms that will no longer apply to these artists and the photographs on view in this exhibition. Here, their stories are being told, works seen, and tributes sung at last.

The exhibition Working Together: Louis Draper and the Kamoinge Workshop is on view at VMFA through October 18, 2020.

The exhibition Working Together: Louis Draper and the Kamoinge Workshop is on view at VMFA through October 18, 2020.

Connecting with the Louis H. Draper Archive

The opportunity to photograph the Louis H. Draper Archive was a labor of love. I grew up knowing this fellow–Richmond native’s work and enjoyed the privilege of both nostalgia and discovery while working on this project.

Draper’s 1971 picture of Fannie Lou Hamer in Essence magazine, along with a plethora of other photographs cut from old publications found at my Grandma Lillie Mae’s home, once layered the walls of my teenage bedroom. With this particular image, I feel the connectivity of kinship. When I see Fannie, I see the women in my family—round face, dark skin, high cheekbones, and ancestral strength. I see myself. The image feels familiar and familial, inspirational and aspirational, ordinary and extraordinary, and now decidedly iconic.

The sheer volume of the Draper Archive particularly fascinates me. It includes manuscripts, screenplays, college notebooks and IDs, résumés, job-acceptance letters, lesson plans, greeting cards, notes, letters to and from colleagues, Kamoinge Workshop meeting minutes, and other documents providing a rich foundation for a groundbreaking and enlightening exhibition. It is so easy to lose oneself in the enormity of such a project, but deadlines are the sharp and needed prick of the bubble that periodically return you to reality.

There are sleeved negatives, contact sheets, slides, prints of all sizes, Kamoinge member portfolio images, images by other photographers who Draper admired, lots and lots of his working prints, test prints with hundreds of the same images in different formats, exposures, and treatments.

A camera from the Draper Archives:

A camera from the Draper Archives:

Leitz Leica M 3 #737925 with Elmar f=5 cm 1:3.5 Lens #1141105

Evidence of his experimentation in 35mm negative and slide film, ½ frame negative film, 126mm film, 110mm size film, medium and large format film. And then there is all of his photography equipment—cameras, flashes, exposure meters, brackets, and camera cases. But wait, there is more. How about a set of keys to a 1969 Chevelle. You name it, Louis Draper saved it, and my hands touched it all.

Kamoinge Interviews: Stories Are for the Telling

During the course of the Draper Archive project, I traveled to New York with Dr. Sarah Eckhardt, VMFA’s Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, and videographer Briget Ganske to interview Kamoinge members Anthony Barboza, Adger Cowans, Daniel Dawson, Jimmie Mannas, Herbert Randall, Herbert Robinson, and Ming Smith.

Kamoinge Workshop photographer Adger Cowans with VMFA’s Dr. Sarah Eckhardt (far right) and videographer Briget Ganske (middle).

Kamoinge Workshop photographer Adger Cowans with VMFA’s Dr. Sarah Eckhardt (far right) and videographer Briget Ganske (middle).

Ming Smith captured during VMFA’s filming for a series of Kamoinge Workshop Artist Interviews.

Ming Smith captured during VMFA’s filming for a series of Kamoinge Workshop Artist Interviews.

Meeting the Kamoinge artists was like seeing family members that I hadn’t seen in a long time—those relatives I encounter on holidays that sit around the kitchen table telling stories of yonder day. I’m usually not a person who is starstruck so I wasn’t that way when I met them. But I soon found myself reflecting back to my childhood bedroom walls that were plastered with photographs. Some of the Kamoinge members spoke about the people who were on those walls. The walls and ceiling of my room were covered with images from the magazines Ebony, Jet, Essence, Sepia, and Right On; the newspaper The Richmond Afro-American; and movie and concert posters. These images gently nudged and pushed me to pursue photography as a career path. There was something familiar about each of the Kamoinge photographers. Perhaps it was the Adger Cowans’s publicity photos from one of my favorite movies growing up, Claudine. Or was it Anthony Barboza’s classic photographs of Isaac Hayes and Pat Evans for Essence magazine or Ming Smith’s iconic images that I would later see in graduate school or maybe it was the Kamoinge Workshop meeting minutes in VMFA’s Draper Archives that I’d recently read. Whatever the reason, I felt as if I knew the Kamoinge members before I met them.

Interviewing Kamoinge Workshop photographer Herb Robinson at his home.

Interviewing Kamoinge Workshop photographer Herb Robinson at his home.

They all spoke highly of Draper, whom they called Lou, and each emphasized how much they appreciated his friendship and mentorship. Each artist had fascinating stories about people they photographed and people they got a chance to meet. Imagine having a conversation with James Baldwin, Romare Bearden, or Grace Jones.

Grace Jones and Pat Evans

Anthony Barboza had great stories. He is one of the first professional photographers to photograph Grace Jones. She wasn’t popular at the time and couldn’t get work. “I gave her a job and she never forgot that,” he said. “If you turn to page 70 in her new book, she dedicates a whole page to me.”

Barboza also talked about Pat Evans coming to his studio for a shoot for Essence magazine. “She came in and said she was going to shave her head and I said, ‘Don’t do that, you’ll never get work.’” When it came time to shoot, Evans arrived with a bald head. Barboza photographed her, and the pictures made her famous. She went on to a successful modeling career. Remembering images I saw of her on album covers for the Ohio Players and Isaac Hayes when I was a teen, I asked Barboza if those photographs were his work. “After I took the photos and she became popular, the agencies would always call the white photographers to photograph her,” he said.

Accordion Book

The first time I saw the accordion book was April 5, 2018. VMFA staff working on the Draper project drove from Manhattan to Long Island to the Shinnecock Nation to the home of Herbert Randall. Someone mentioned a Christmas gift that Anthony Barboza gave each Kamoinge member. It was an accordion book with a portrait taken by Barboza of each member placed side-by-side with the member’s self-selected favorite photograph. Until our visit with Randall, we had not seen the book, which was gifted in the `70s. When we asked him about it, Randall went to another room of his home and came back with the book. It was in mint condition. I could tell immediately that Dr. Eckhardt loved the piece and that it would likely be in the exhibition. We all loved it. Barboza brought the original artist’s proof to the studio during another interview session. He had Jimmie Mannas and Danny Dawson autograph it, since they had not signed it before. That original artist’s proof is the version of the book that is featured in the exhibition. After photographing the accordion book, I could not imagine how it would be displayed. Nonetheless, the VMFA exhibitions team did a remarkable job on the casing for the piece, making it one of my favorites in the exhibition.

Anthony Barboza pictured with the accordion book he gifted his fellow Kamoinge Workshop members.

Anthony Barboza pictured with the accordion book he gifted his fellow Kamoinge Workshop members.

Mahalia Jackson

Sunday mornings with Mahalia Jackson on the radio was the ritual at my Grandma Flora Bell’s house. Gospel radio filled the air along with the aromas of breakfast and Sunday dinner in the making. Mahalia was a big deal in the gospel industry back in the day. And once upon a time, I could recognize her voice anywhere. I have vivid childhood memories of watching her on television and listening to her on the radio. So when I walked into Herb Robinson’s house, along with the VMFA team, to interview him, my eyes were captured by Robinson’s photograph of Mahalia above his piano. I knew who she was right away—even though her back is to the camera. The image is striking, and it transported me back to Flora Bell’s kitchen on Sunday mornings. The smell of bacon frying and rolls baking permeating the air and the unmistakable contralto voice of Mahalia Jackson singing “How I Got Over” coupled with my grandmother saying “turn that up” and me standing on a stool to reach the radio is a reminder that photographs can take us back to a place we want to remember forever.

Photograph of Mahalia Jackson (left) on view at VMFA.

Photograph of Mahalia Jackson (left) on view at VMFA.