01: Introduction

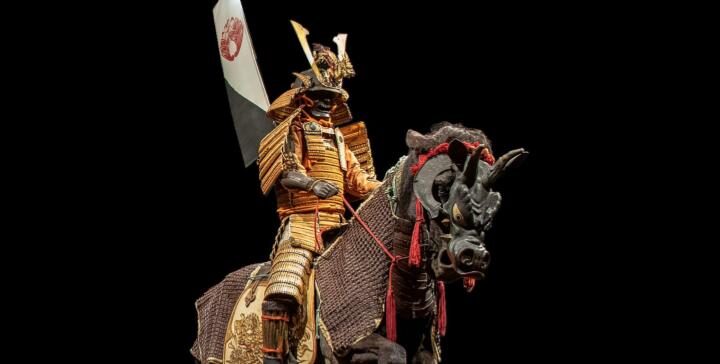

Image: Nuinobedō tōsei gusoku armor and military equipment, Late Momoyama period, c. 1600 (chest armor, helmet bowl, shoulder guards); remounted mid-Edo period, mid-18th century, iron, lacquer, gold, bronze, silver, leather, wood, horsehair, hemp, brocade, steel. © The Ann & Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Museum, Dallas. Photo: Brad Flowers

Welcome to VMFA and the exhibition Samurai Armor from the Collection of Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller. This exhibition is dedicated to Japanese armor and showcases more than 140 works from one of the world’s largest and most significant private collections of samurai armor.

The samurai, whose name means “those who serve”, rose to preeminence as masterful swordsmen, archers, and equestrians beginning in the 12th century and dominated political, social, and cultural aspects of Japan until their fall in the late 19th century.

The incredible objects in this exhibition not only speak to the importance of samurai culture in Japan, but they also provide insights into the individuals who owned, made, and wore samurai armor. Throughout this exhibition, we’ll discover how these objects reveal important aspects of samurai culture, including the familial structures that bound wearers, makers, and owners to the samurai way of life for over 700 years.

This audio guide consists of 11 stops and each stop is indicated by an audio symbol next to a work of art. If you are using an audio wand, input the stop number located on the label next to the audio symbol. If you are using your mobile device, select the audio file associated with the stops for each room.

In addition to the information contained within this guide, be sure to pay attention to the large wall text panels that introduce each gallery and the labels that accompany most objects – these will provide additional context for the people and stories we will explore.

Our first official stop is a rare, fully intact set of armor. There is a lot to see here, so allow yourself a moment to take it all in. As you are looking, you may notice that there are many parts and pieces that make up a full set of samurai armor – not to mention the amount of artistic skill and craftsmanship it would take to create one. You may also have noticed that along with a full suit of armor, this display also contains additional weaponry, armor, and garments.

Now that you have spent some time looking, perhaps you are wondering how someone might fight in something this intricate and complex. This particular set was made around the year 1600 and could very well have been used on the battlefield but many suits included in this exhibition would have been worn during ceremonies. We will explore the concepts of ceremony and battle further in upcoming stops.

You may also be wondering who this armor belonged to. It is believed to have been owned by a branch of the Mōri clan, one of the most important daimyo families in Japanese history. Daimyo were powerful feudal lords who had great control over vast territories. They were loyal to the shogun, or military dictator, who granted lands to daimyo in return for their military support. Daimyo provided this military support through the service of their own samurai warriors. You will hear more about daimyo throughout this guide.

Let’s focus on a couple of components of this set to better understand the connection this armor has to the Mōri clan. We will start with the helmet, as they were considered the most important part of a set of armor. The design of a samurai helmet went beyond mere protection of the head. For example, the decorative elements on this helmet were not only included for aesthetic reasons – they also linked the wearer to a particular clan. With armor that was worn in combat, these features also had the practical purpose of standing out on the battlefield.

The frontal ornament on the helmet represents two paulownia leaves with a 16-leaf imperial chrysanthemum at the center. The paulownia is a hardwood tree native to East Asia, and the chrysanthemum flower, while not originally native to Japan, became an important symbol for the imperial family. The side ornaments on this helmet bear the paulownia crest, or kiri mon, associated, in this case, with the Mōri family. The kiri mon is encircled with three leaves of the paulownia topped by three budding stems. As you look around this display, you may notice that the helmet is not the only object to hold the kiri mon. You will see that this case also contains two surcoats to the left and the right. Both bear the family crests on the back, although only the yellow surcoat’s crest is visible here.

Now draw your attention to the fan in the center of the armor. Perhaps the design of a red circle on a light background looks familiar to you. It represents the sun and is the same symbol we see today on the Japanese flag. It has been used as a symbol in Japan for over a thousand years.

But why might a samurai hold a fan? On the battlefield, commanders of samurai used something called a gunsen, or war fan. The gunsen was a symbol of the supreme commander of the army and they would use it to signal samurai movement on the battlefield. These war fans could also be used as shields, even offering some protection from arrows, wind, or rocks. Fans were also thought to offer some spiritual protection as the act of fanning was thought to pacify evil spirits.

In the late 16th century, this set of armor belonged to daimyo Kobayakawa Takakage who was originally a member of the Mōri Motonari family. It is believed that the suit was a gift from daimyo and powerful warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi for his efforts in the ultimately unsuccessful invasion of Korea. This gift points to the important status armor held as a symbol of strength and authority, often given in exchange for military service.

Warfare was common throughout Japan for hundreds of years. Our next object shows a scene from a well-known literary tale of an epic battle between clans.