The Rosetta Stone features script in three different writing systems: Greek, demotic, and hieroglyphic. In 1799, during Napoleon’s campaign to conquer Egypt, French soldiers discovered the stone near the village of Rosetta. Linguists later used their knowledge of Greek to decode the demotic and hieroglyphic scripts. By identifying certain ancient Egyptian words, researchers were able to translate the Stone’s message: a decree that says priests of a temple in Memphis support ht reign of thirteen-year old Ptolemy V, on the first anniversary of his coronation.

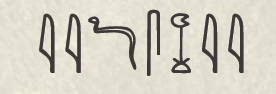

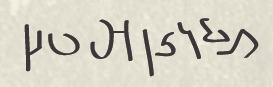

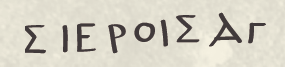

The Rosetta Stone’s three scripts appear in this order:

- Hieroglyphic script : ancient Egyptian script, used by Egyptian kings and priests for formal use.

- Demotic script: ancient Egyptian script used for everyday writing.

- Ancient Greek: official language of the Ptolemaic rulers and the common language of the Mediterranean world at this time.

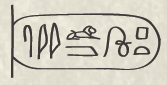

By analyzing the Rosetta Stone and other texts, the young French scholar Jean-Francois Champollion (1790-1832) made a significant advance in understanding ancient Egyptian writing when he pieced together hieroglyphs used to write the names of non-Egyptian rulers. These names could be recognized because, following Egyptian conventions, they were written in a cartouche, and oval-shaped border used only for the names of very important people. (The cartouches seen on the Rosetta Stone enclose the name Ptolemy.)

Following France’s defeat in Egypt, the Rosetta Stone was surrendered to the British authorities and given to King George III, who gave it to the British Museum of Art in London. The Rosetta Stone, made in 196 BC (Egypt’s Ptolemaic Period), has been on display in London for more than two hundred years.