Art in Depth: Kehinde Wiley at VMFA

Learn more about two works of art by artist Kehinde Wiley on view at VMFA!

Kehinde Wiley, American, born 1977, Rumors of War, 2019, Bronze with stone pedestal

Virginia Sargeant Reynolds in memory of her husband, Richard S. Reynolds Jr., by exchange, and the Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment, 2019.39

Originally presented in Times Square by Times Square Arts in partnership with Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and Sean Kelly, New York

“The inspiration for Rumors of War is war – is an engagement with violence. Art and violence have for an eternity held a strong narrative grip with each other. Rumors of War attempts to use the language of equestrian portraiture to both embrace and subsume the fetishization of state violence. New York and Times Square in particular sit at the crossroads of human movement on a global scale. To have the Rumors of War sculpture presented in such a context lays bare the scope and scale of the project in its conceit to expose the beautiful and terrible potentiality of art to sculpt the language of domination.”

–Kehinde Wiley

Introduction

In Rumors of War, American artist Kehinde Wiley depicts a contemporary African American male on horseback. Inspired by the history of European equestrian portraiture, this sculpture is his largest creation to date. It’s thematically related to a series of paintings he made in the early 2000s (also called Rumors of War) in which the artist replaced traditional white subjects on horseback with young Black men wearing current fashions. At that time, his paintings were a reaction to the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as part of his ongoing investigation of traditional European art and concepts of masculinity. Nearly two decades later, Wiley produced this public sculpture as a response to Confederate monuments, particularly those in Richmond, Virginia.

The series and statue both take their name from a biblical phrase found in Matthew 24:6, which suggests that wars will be part of the human experience until the end of time. As Wiley developed his ideas for VMFA’s equestrian statue, he contemplated the civil unrest, violent conflicts, and need for new directions in the United States, rather than the troubles in the Middle East. Wiley explains his firm belief in the power of art to bring about change in these words:

“The idea is that in the ‘change times,’ there will be wars and rumors of war.

… And there are moments where art has to step in.”

Although Rumors of War now stands at the entrance to VMFA, Wiley first unveiled his work in New York City’s Times Square, which he describes as a “crossroads of human movement on a global scale.” The sculpture then traveled to Richmond, where it was unveiled on December 10, 2019, amid huge crowds on the museum’s grounds and across historic Arthur Ashe Boulevard.

Rumors of War in its first location in Times Square, New York, New York.

Watch the unveiling of Rumors of War at VMFA in this video!

Kehinde Wiley

Kehinde Wiley is an American painter (born 1977, Los Angeles) who splits his time between studios in New York, China, and Senegal. As a child, Wiley’s mother enrolled him in weekend art classes where he learned to paint and draw. He often recalls his frequent field trips to local museums as a child, and the lasting impact those visits had on him. His artistic interests and talents continued to grow throughout his youth, and in 1999, he received his BFA from San Francisco Art Institute, followed by his MFA from Yale University in 2001. After leaving Yale, Wiley became artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem where he began to rethink portraiture and develop his innovative method of “street casting.” Wiley’s career has focused on addressing and remedying the absence of Black and brown men and women in our dominant visual, historical, and cultural narratives. Wiley’s subjects have ranged from street-cast individuals the artist encountered while traveling around the world to many of the most important and well-known African American figures, including President Barack Obama, The Notorious B.I.G., Nick Cave, LL Cool J, and Carrie Mae Weems.

Learn more about Wiley’s street casting process in this video!

Wiley’s Approach to Representation

Why did Kehinde Wiley decide to reinterpret historical artworks by replacing traditional white subjects with contemporary Black figures? Wiley observes that while growing up in Los Angeles, he often frequented the Los Angeles County Museum of Art where he was drawn to works that depicted the Black experience. He recognized from a young age, however, that African American artists and representations of Black culture were not commonly seen in museum settings. His solution was to “repaint” history. He explains, “I do it because I want to see people who look like me.”

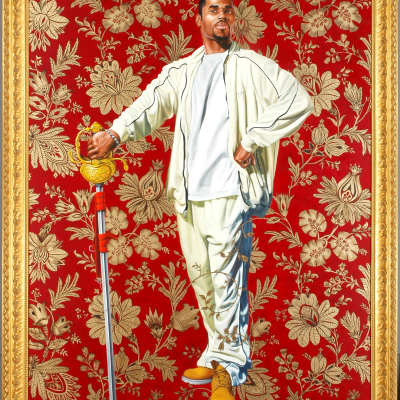

In addition to Rumors of War, VMFA’s collection includes another work by Wiley in which he implements his own take on traditional European portraiture. His oil painting Willem van Heythuysen is a reimagining of the Frans Hals work of the same name, currently in the collection of the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, Germany. Wiley places a fashionably dressed Black man in the same pose as the Dutch merchant. The figure leans on an ornate sword, just as the original Willem van Heythuysen did in 1625. By placing an ordinary person of color within the classical, European artistic narrative, Wiley invites viewers to reframe their perceptions of Black male identity.

Kehinde Wiley’s Willem van Heythuysen, 2016, and Frans Hal’s Willem van Heythuysen, c.1625.

Inspiration for Rumors of War

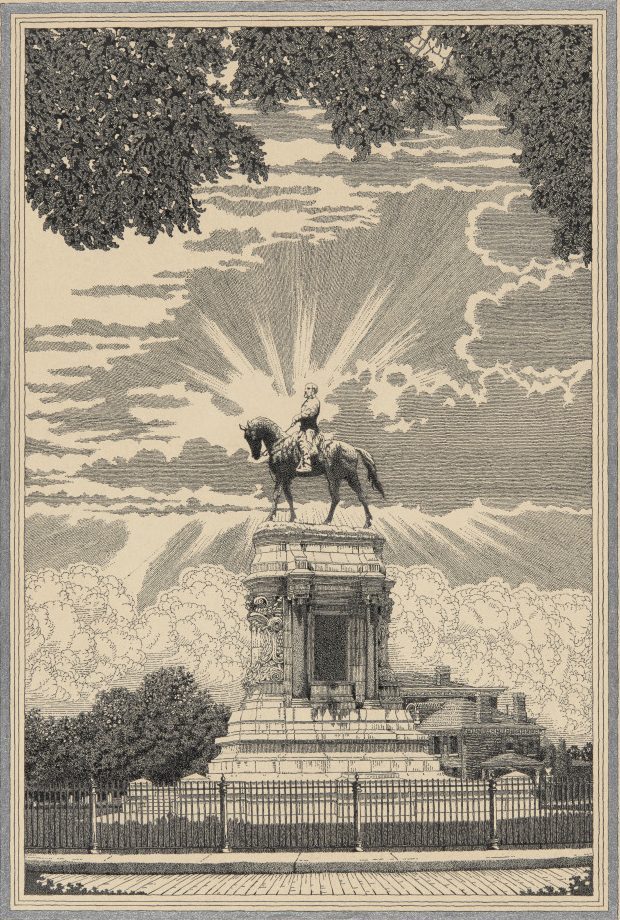

J.E.B. Stuart Monument as previously seen on Monument Avenue in Richmond, VA.

Rumors of War, Wiley’s monumental bronze sculpture, is the artist’s direct response to the Confederate sculptures that populate the United States, particularly in the South. He developed the idea for this sculpture during a 2016 visit to Richmond in conjunction with A New Republic, an exhibition of his work at VMFA. While visiting, he traveled down Monument Ave and was stunned by the monuments.

He asked, “What does it feel like if you are Black and walking beneath this? We come from a beautiful, fractured situation. Let’s take these fractured pieces and put them back together.”

This sculpture echoes the form and composition of a statue of Confederate Army General James Ewell Brown “J.E.B.” Stuart that was located on Monument Avenue during Wiley’s 2016 visit to VMFA. As with the original sculpture, Wiley’s rider strikes a heroic pose while mounted on a powerful horse. However, in Wiley’s sculpture, the figure is a young Black male clad in streetwear—commemorating the African American youth who are living through the social and political battles taking place across our nation.

In recent years, efforts to better contextualize controversial Confederate monuments have resulted in both the addition and removal of monuments in more than 30 states. Installing Rumors of War in the former capital of the Confederacy positions Wiley’s work as a counteractive symbol of erased cultural narratives—the Black body of Wiley’s sculpture becomes a contemporary hero calling for change.

The J.E.B. Stuart monument that provided the impetus for Wiley’s work was removed from its location on Monument Avenue on July 7, 2020, following national—and local—racial justice protests in response to the murder of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and far too many others.

Rumors of War: One Year Later

The 2020-2021 Museum Leaders in Training cohort produced the video about Rumors of War offered below. Working with VMFA staff, M.LiT students explored the contextualization of Wiley’s Rumors of War in Richmond and considered the themes of representation, race, gender, and power. Students interviewed VMFA staff and the staff of partner institutions, local community members, and organizers to capture and include a variety of perspectives on the subject. The individuals interviewed by the students include Free Bangura, Princess Blanding, Valerie Cassel Oliver, Alex Criqui, Hamilton Glass, Dustin Klein, Sandra Sellars, Luis Vasquez La Roche, and Sandy Williams IV.

Learn more about Museum Leaders in Training!

To celebrate the one-year anniversary of the unveiling of Rumors of War by Kehinde Wiley, VMFA commissioned Dustin Klein and Alex Criqui, Richmond-based artists who have garnered national attention for their thought-provoking projections onto the Robert E. Lee statue on Monument Avenue, to create a piece for VMFA. Klein and Criqui wove together a captivating visual presentation of animation, digital collage, and projection mapping, which was projected onto the outer wall of the museum near Rumors of War. Audio recordings of Kehinde Wiley’s 2019 remarks filled the air, amplifying the unanticipated, yet profound and timely, relevance of Rumors of War and the dialogue it continues to inspire.

Monument Avenue in Context

Racial Disparities in the Post Civil-War South

The immediate aftermath of the Civil War, known as Reconstruction (1863-1877), was a period of large-scale social upheavals and internal strife within the recently defeated Southern states. Many former Confederates continued to strongly support state sovereignty, while opposing federal interference in state affairs. This opposition prevented progress toward reconciling differences in political beliefs—and prevented the establishment of equality for all. The Emancipation Proclamation, a speech given by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863, established the freedom of enslaved people in Confederate states. As the war continued, Lincoln consistently advocated a progressive platform that promoted the equality of African Americans in the United States, including the passage of the 13th amendment in January 1865. Tragically, he was assassinated in April 1865, eight months before the amendment was ratified in December of the same year. His successor, former Vice President Andrew Johnson, was by comparison a firm believer in state’s rights. During his presidential term, Johnson supported policies that restored white politicians to leadership positions in Southern states and reversed many of Lincoln’s programs for Reconstruction. These policies led to the implementation of deplorable policies, including the Black Codes of 1865-1866 (also known as Black Laws).

The Black Codes complied with federal legislation to a degree, granting some freedoms to African Americans, such as the right to buy and own property. Loopholes were found, however, that made it possible to restrict and regulate the daily lives, occupations, and wages of African Americans.

Johnson also refused to support the passage of the 14th Amendment, which called for equal protection under the law. Although the amendment was finally ratified without his support in July 1868, Southern state governments continued to find methods for preventing African Americans from fully exercising their newly legislated rights.

The 15th Amendment, ratified in December 1870, extended the right to vote to African American men, which prompted Southern leaders to institute literacy tests and poll taxes to prevent Black men from voting.

The complete reunification of all the Confederate states did not happen until 1870—and Virginia was the third to last of those states to be readmitted into the Union in that year.

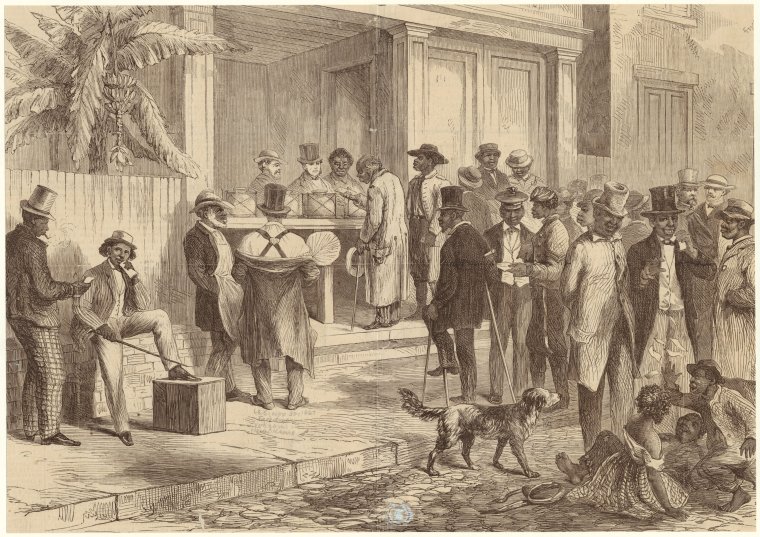

"Freedmen Voting in New Orleans," 1867, Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Lost Cause Ideology

From the end of the 19th century through the early 20th century, Southerners sought ways to cope with their defeat in the Civil War, while commemorating the values and beliefs of the old South. The term “Lost Cause,” which was taken from the book The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates by Edward Pollard, became a term that encompassed the South’s military defeat and the loss of a pre-war Southern way of life. The Lost Cause ideology was characterized by a common set of beliefs, including a fundamental belief in white supremacy; the assertion that the war was fought not over the institution of slavery, but over states’ rights; that enslaved people were actually devoted to their masters; and that the war was justified in the eyes of God, in part because slavery was a benevolent institution that brought Christianity to people of African descent.

The ideals of the Lost Cause were promoted in numerous ways, from the production of literary works and textbooks to commemorative activities, such as the celebration of Confederate Memorial Day. The most visibly striking of these efforts may well be the widespread erection of Confederate monuments across the Southern states, honoring the political and military leaders who had supported the Southern cause. Waves of enthusiasm supported the construction of these statues from 1900 to 1920 and 1950 to 1960, commemorating the 50th and 100th anniversaries of the Civil War respectively. In these timeframes, Southern monuments and statues served as propaganda, conveying to Black Southerners the message that their efforts to secure civil rights were futile. Confederate ideology remained a central part of Southern life—and the Lost Cause narrative became an effective tactic for suppressing African American freedom.

In recent times, steps have been taken to combat this ideology, particularly with the removal of Confederate statues all over the American South, most notably in New Orleans, Louisiana; Richmond, Virginia; Memphis, Tennessee; and Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Race Relations Reconstruction Richmond

In Richmond and many other Southern cities and towns, the Reconstruction period offered a brief window of opportunity for African Americans. While elite, white conservatives pushed for policies that would grant them authority over African Americans, many people of color were able to take advantage of new possibilities, such as running for public office or establishing businesses. (In Richmond’s Jackson Ward neighborhood, Maggie L. Walker (1864-1934) became the first African American woman to found a bank.)

By the late 1880s, however, white conservatives regained control of Richmond’s political landscape and gradually embedded racial policies into governmental law to restrict and disenfranchise African Americans, as exemplified by Jim Crow Laws (laws that required segregation of public facilities under the guise of “separate but equal”).

Group of freedmen, including children, gathered by a canal in Richmond, Va., in 1865. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Dugard Stewart Walker, Statue of Robert E. Lee, 1936, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Statue Mania and Richmond's Monument Avenue

From the 1870s to the 1920s, various groups in the United States worked to heal the wounds of war and rebuild national unity in tangible form through the erection of monuments honoring historical figures. As Erika Doss explains in her essay, “Memorial Mania: Public Feeling in America,” the desire to assert a “national ideology of militarism and masculinity” led to a period she describes as “statue mania.” By producing thousands of monuments dedicated to figures from Christopher Columbus to Robert E. Lee during this era, the United States was able to instill in the public consciousness a collective, white-dominated, and monolithic national history.

In the South, “statue mania” at the turn of the century focused primarily on reinvigorating Southern states after the Civil War. Former Confederate cities and towns memorialized Confederate military leaders, soldiers, and other symbols of the old South. In Richmond, this initiative inspired a commission for a sculpture of Robert E. Lee to be created by the French artist Antonin Mercié. A few years after his Lee statue was unveiled in 1890, a grand avenue was constructed with Lee as its centerpiece.

Over the next decade, many wealthy Richmonders built stately homes along “Monument Avenue.” Soon, other Confederate figures, including Jefferson Davis (1907) and J.E.B. Stuart (1907), were added to adorn the tree-lined street. The author Kirk Savage in his book Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves, views these “Lost Cause” monuments as attempts to justify the Southern secession and to reframe the war “as a violent conflict among white men over high principles, having nothing to do with slavery” but everything to do with honorable duty, valor, and the right to local sovereignty. In this sense, the Confederate monuments were visualizations of a continued legacy of white power from the old regime to the next – from the Confederacy to the modern South.

Read more about the history of Monument Avenue through On Monument Avenue with online exhibits about the origins and development of Monument Avenue featuring objects from the American Civil War Museum, the Library of Virginia, The Valentine, and the Virginia Museum of History and Culture.

The Lee Statue unveiling on Monument Avenue, May 29, 1890. Photo courtesy of Cook Collection, The Valentine.

Monument Avenue Today

In the summer of 2020, Confederate memorial statues became the focus of protest and graffiti as part of the nationwide public outcry over the death of an unarmed Black man named George Floyd, who was killed by police officers in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Virginia Governor Ralph Northam and Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney encouraged the passing of the legislation required to have these symbols of oppression removed from Richmond’s most famous street, including the J.E.B. Stuart monument, the work that prompted Wiley to create Rumors of War.

The Robert E. Lee statue became the central gathering place for protesters who reclaimed and renamed the area the Marcus Davis Peters Circle. It is the only Confederate memorial statue that still remains on Monument Avenue; its fate is under discussion due to legal ramifications having to do with state property laws.

Explore Richmond’s response to racial injustice, both past and present in Richmond Uprising, an online exhibition from The American Civil War Museum.

Learn more about Rumors of War and Monument Avenue with Monumental Conversations an Augmented Reality History Tour.

Robert E. Lee Statue on Monument Avenue, July 2020. Photo by: Katie Domurat.

ENGAGEMENT IDEAS AND DISCUSSION PROMPTS

Consider the following groups of questions for reflection. Pick and choose or mix and match the ones that best suit your group of audience!

Who or what is represented in installations in our public spaces today?

- Do the monuments we see around us today reflect all of us?

- Why is it important to think about who might be missing from these installations.

- Wiley’s sculpture invites us to think more deeply about monuments and memorials. Rumors of War directly addresses the lack of African Americans represented and honored in public spaces across the country.

How do we tell stories about the past?

- How can we tell new stories about the past?

- How can we add new voices to the ones represented by monuments today?

- Can public monuments help us question and revise our understanding of the past?

- What story would you choose to represent in a monument?

How have the Civil War and/or other past eras and events been represented in the public monuments we see today?

- What viewpoints are represented in these statues and memorials?

- How will future generations interpret the public monuments we leave behind?

- What are we encouraging them to remember?

- Wiley’s work helps us consider these and other questions about how we choose to present our collective history through public monuments and memorials.

- It might be of interest for this discussion to examine a graph produced by the Virginia Department of Historic Resources that illustrates the correlation between the time in which Virginia’s Confederate Monuments were erected and the dates of several pivotal landmarks in Civil Rights history. (See page 31 in the 2016 report by Virginia Governor McAuliffe’s Monuments Work Group titled Recommendations for Community Engagement Regarding Confederate Monuments.)

Can monuments represent groups of people or ideas?

- Does Wiley’s sculpture represent a specific individual?

- Why do you think he decided to depict an African American rider?

- What ideas or values might this work be reflecting?

- Does he succeed in prompting you to re-evaluate the history of monuments?

Do you think Rumors of War is an effective work of art?

- Look closely at the images of the JEB Stuart sculpture and Rumors of War.

- How does Wiley’s statue differ from the Confederate memorial monument?

- What effect do these changes have?

- What symbols does Wiley use to create a new story? Are they effective? Why?

Location, Location, Location! Why does placement matter?

- Can the meaning of a monument change if it is placed in a different context?

- Consider the location of Rumors of War in Times Square versus its location on the VMFA’s front lawn. Take some time to learn about the history of the VMFA grounds. How does the meaning or significance of Rumors of War change once you understand this history?

Additional Questions for Discussion

- What do monuments mean to you?

- Do you think we need monuments?

- What purposes do monuments serve?

- Who should decide which public monuments we have?

- What kind of monument would you like to see and where would you place it?

- What if someone disagrees with your opinions for a monument?

- How would you proceed with a respectful discussion?

- Would their opinion change how you view the monument?

- What would a monument designed to represent the values of today’s world look like?

- Should public monuments be permanent? If so, why?

- If not, what are other possible public methods for commemorating the past or present?

More Resources

Richmond’s Monuments (an online exhibition from The Valentine)

Did you know that the first public monument erected by European settlers in what would become Richmond City was a cross placed on the banks of the James River in 1607? Did you know that plans are currently underway to establish a monument celebrating Virginia Women on the State Capitol grounds and an Emancipation Monument on Brown’s Island? Richmonders have long marked the landscape to reflect collective values and debated their meaning and role. Today, this dialogue has evolved locally and nationally as citizens continue to discuss what we have chosen to commemorate and what we have chosen to forget.

Sources

Artnet News (October 3, 2019). Artist Kehinde Wiley’s First Public Sculpture in Times Square Is a Powerful a Rejoinder to Confederate-Era Monuments. Retrieved June 3, 2021, from https://news.artnet.com/art-world/kehinde-wiley-times-square-2-1669708

Clouser, Haley. (2019). VMFA Tour Guide Packet Kehinde Wiley’s Rumors of War. Richmond, VA.

Curran, Colleen. (Dec 10, 2019). There’s something changing in these winds’: Kehinde Wiley’s ‘Rumors of War’ unveiled in Richmond. Retrieved June 3, 2021, from https://richmond.com/news/local/theres-something-changing-in-these-winds-kehinde-wileys-rumors-of-war-unveiled-in-richmond/article_1e1abd39-69c4-502d-b0c6-28f3921312aa.html

Doss, Erika. Memorial Mania: Public Feeling in America, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Kehinde Wiley. Retrieved February 15, 2021, from https://www.stephenfriedman.com/artists/kehinde-wiley/.

Kehinde Wiley Studio. Retrieved February 15, 2021, from https://kehindewiley.com/.

Landrieu, M. (2018, March 12). How I learned about the “cult of the lost cause”. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-i-learned-about-cult-lost-cause-180968426/

Levinson, Sanford. Written in Stone: Public Monuments in Changing Societies. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1998.

Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm. “On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life.” In Untimely Meditations. Edited by Daniel Breazeale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, University of Michigan, MPublishing, 1997.

O’Brien, John Thomas. From Bondage to Citizenship: The Richmond Black Community, 1865–1870. New York: Garland, 1990.

Robinson, Mark.“Mayor Stoney: Commission to consider removal of Confederate statues on Richmond’s Monument Ave.” Richmond Time-Dispatch. Last modified August 16, 2017. http://www.richmond.com/news/local/city-of-richmond/mayor-stoney-commission-to-consider-removal-of-confederate-statues-on/article_0120e8e9-d3f8-5b9e-8343-69902df255a6.html.

Robinson, Mark. “Mayor Stoney: Richmond’s Confederate monuments should stay with context added; commission’s mission remains the same.” Richmond Times-Dispatch. Last modified August 14, 2017. http://www.richmond.com/news/local/city-of-richmond/mayor-stoney-richmond-s-confederate-monuments-should-stay-with-context/article_b8cbb743-410f-520f-9197-2a58450d128a.html.

Savage, Kirk. Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America.Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Sculpture created By Kehinde Wiley For VMFA. Retrieved February 15, 2021, from https://www.vmfa.museum/about/rumors-of-war/.

Upton, Dell. Introduction in What Can and Can’t Be Said: Race, Uplift, and Monument Building in the Contemporary South. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2015.

Upton, Dell. “Why Do Contemporary Monuments Talk So Much?” In Commemoration in America: Essays on Monuments, Memorialization, and Memory. Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2013.