TRADITIONS OF THE SAMURAI

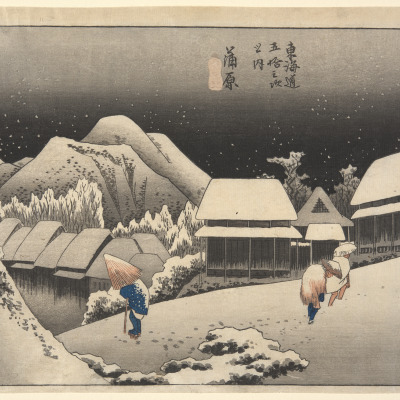

Woodblock Prints

The woodblock print series the Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido Road, designed by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) and first published in 1833–34, contains fifty-five images among the most recognizable in all Japanese art. The Tokaido was a well-known pedestrian highway that connected Edo to Japan’s former capital of Kyoto, stretching roughly 320 miles along the eastern coastline of its central island of Honshu. First established in the 8th century, the Tokaido became increasingly trafficked in the early 1600s. This was due to the shogun’s requirement that hundreds of regional lords (daimyo) from across Japan travel annually to Edo where their families resided year-round, in effect centralizing his political power.