Indigenous American Artists at VMFA

VMFA’s collection includes art by Indigenous artists from across North America, past and present. The works showcased here represent a diverse range of creative practices, reflecting the ways in which Indigenous artists engage with their community’s worldviews, histories, and ways of knowing. Art by Indigenous artists can be found in the Evans Court Gallery and in the American Art Galleries.

For our elders and ancestors, whose voices were silenced but whose courage created us.

—Karenne Wood, Monacan Indian Nation

The Commonwealth of Virginia was one of the first points of contact between Indigenous peoples and European settlers. The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts acknowledges the presence of the Powhatan Chiefdom and the Monacan Nation on the land on which the museum now stands and honors all the indigenous peoples of Virginia, past and present. Today, Virginia is home to seven federally recognized Tribes: Chickahominy Indian Tribe, Chickahominy Indian Tribe – Eastern Division, Monacan Indian Nation, Nansemond Indian Tribe, Pamunkey Indian Tribe, Rappahannock Tribe, and the Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe. In addition to these federally recognized Tribes, the Commonwealth of Virginia also recognizes the Cheroenhaka (Nottoway) Indian Tribe, Mattaponi Indian Tribe, Nottoway Indian Tribe of Virginia, and the Patawomeck Indian Tribe of Virginia. These 11 tribes represent three linguistic groups in Virginia: Algonquian, Siouan and Iroquoian.

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts seeks to honor the history of this land and to maintain and nurture our relationships with these tribes. We are committed to building on these partnerships in our approach to collecting, programming, and providing visitor experiences. It is with humility that we look to our past, and with hope that we look to our future.

ON VIEW IN THE ATRIUM

Hiawatha's Marriage, modeled 1866, carved 1870, Edmonia Lewis (American/Mississauga Ojibwe, 1844-1907), marble. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, J. Hardwood and Louise B. Cochrane Fund, 2024.26

Hiawatha’s Marriage, Edmonia Lewis

Edmonia Lewis’s Indigenous identity (Mississauga Ojibwe) contributed significantly to her interest in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1855 enormously popular epic poem The Song of Hiawatha, the literary source for this sculpture. Lewis’s response to Longfellow’s verse visualizes a passage from part X of the poem in which Hiawatha and Minnehaha “clasp … hands,” symbolizing not only their marriage but also the peace between their respective tribes, the Ojibwe and the Dakota.

Hiawatha’s Marriage merges Westernized idealism and realism—the latter through the hair styles, arrows and quiver, and eagle feathers and the former by way of the generalized facial features, pronounced brows, high foreheads, and the gaze of the figures’ faces. Lewis carefully incised intricate, symmetrical patterns into the couple’s moccasins, Minnehaha’s shawl, and Hiawatha’s quiver. The moccasins, in particular, may reference Ojibwe or Dakota beadwork motifs, both of which are known for balanced, vibrant floral designs.

ON VIEW IN AMERICAN GALLERIES

Platter, Maria and Julian Martinez

Although she learned pottery as a child, Maria Martinez began experimenting with new methods after an archaeological excavation of the Pajarito Plateau region led her to make recreations of vessels based on excavated pottery shards. She and her husband, Julian Martinez, are widely known for leading a revitalization of ancestral Pueblo pottery techniques in the years following the excavation. Working together, Maria formed and polished their pottery and Julian painted the designs. This platter is an example of the “black-on-black” style that the couple invented, and which they taught to many other tribal members in their lifetimes. Recalling an early conversation with Julian about sharing their methods with other San Ildefonso potters, Maria recounted the couples’ agreement that “pottery-making belongs to everybody [in San Ildefonso]” and that “if [creating] it helps one family, it can help all the families.” Their work sparked increased economic and creative opportunities at San Ildefonso Pueblo, which continues to be a hub for artistic expression to this day.

Aeronauts: Steu and Cuda, Virgil Ortiz

Made in the style of Cochiti monos, a satirical form of social commentary originated by 19th century Cochiti potters, Virgil Ortiz’s Steu and Cuda are two figures from the artist’s Pueblo Revolt 1880/2180 project, a futuristic, sci-fi retelling of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. A pivotal event in the history of Pueblo resistance in which all the Pueblo tribes worked together to revolt against Spanish incursion, Ortiz sometimes refer to the Pueblo Revolt as the “first American revolution.” In Ortiz’s artistic universe, Steu and Cuda are aeronautical commanders engaged in warfare with invading forces, focused on rescuing clay artifacts from the battlefield before they are destroyed by an enemy militia. In Ortiz’s words, “[Steu and Cuda] know that challenges and persecution will continue, so it is imperative to preserve and protect their clay, culture, language, and traditions from extinction,” highlighting the connections between art, creativity, and ongoing Indigenous resistance.

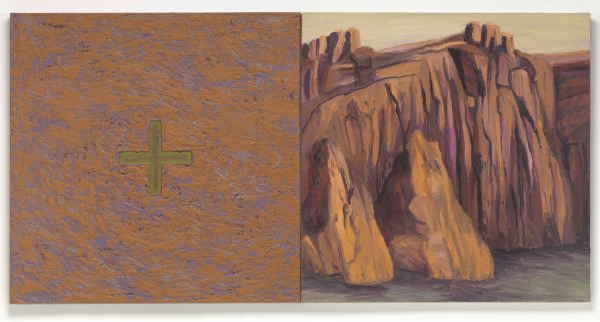

Four Directions/Stillness, Kay WalkingStick

Four Directions/Stillness is a diptych, meaning it is one painting made of two parts. Painted by the artist as a recollection of a trip to Bandolier National Monument in New Mexico, this work represents Kay WalkingStick’s personal memory of the landscape there. On the left canvas, the artist included a cross in reference to the four cardinal directions, which hold special significance within some Indigenous communities’ cosmologies. For this body of work, WalkingStick painted with saponified wax (a combination of beeswax and other additives) mixed with acrylic paint, alternately building up layers and scraping away to create depth and texture. Notice the potential points of connection and difference between the canvases.

What feelings might WalkingStick be trying to evoke about her physical or spiritual experience of place?

ON VIEW IN EVANS COURT GALLERY

Butterfly Whorl, Susan Point

In Butterfly Whorl, Susan Point, a Coast Salish artist from Musqueam First Nation, connects flowing lines in a composition that uses Coast Salish designs like circles and trigons to render the titular creature. The work’s form pays homage to wooden spindle whorls used in Coast Salish weaving, a culturally significant artform traditionally done by women. Coast Salish weavers use whorls that, like Butterfly Whorl, are often intricately carved with designs or images, to spin their own yarn. The yarn is then women to produce vibrant blankets that, through a Coast Salish worldview, confer spiritual protection and are imbued with the stories and understandings of their makers. When Point first began making largescale sculpture, it was a creative field typically reserved for men. Point has since embraced the sculptural medium to experiment with ancestral Coast Salish visual languages while honoring the practices of Coast Salish women artists.

Seal/Baby, David Ruben Piqtoukun

David Ruben Piqtoukun’s Seal/Baby might be referencing Sedna, a young Inuk woman who transformed into a sea goddess with a human torso and a fish tail. Sedna’s fingers were cut off as she held onto the side of her father’s kayak and from them grew all the creatures that live in the sea. Sedna has dominion over all the water animals that Inuit hunt for sustenance, including seals, which are central to Inuit life in both cultural traditions and as a source of survival. As a small child, Piqtoukun and his family lived nomadically, hunting and fishing for subsistence along the Arctic coastline in Inuit territories. At the age of five, Piqtoukun, like many other Indigenous children at the time, was forced by the Canadian government to attend residential school away from his family. As an emerging artist, Piqtouken began collecting ancestral stories from his parents and elders, re-establishing cultural bonds that has been damaged by residential school. Many of these stories are reflected in his work through a process that the artist characterizes as an interpretation of “Inuit traditional mythology, utilizing my artwork as sources of learning and teaching.”

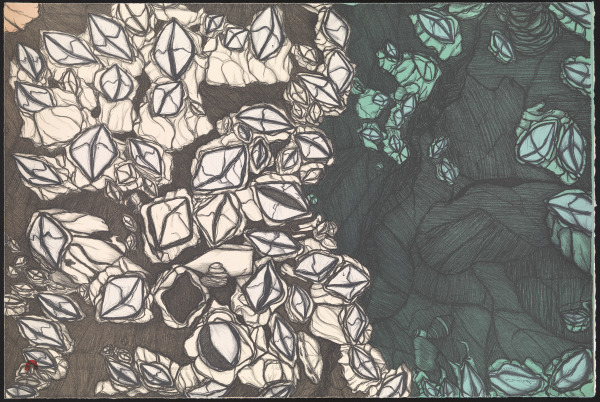

Barnacles, Padloo Samayualie

Padloo Samayualie is from Kinngait (also called Cape Dorset), an Inuit community known for a strong history of graphic arts, including printmaking. As an artist, Samayualie works across many mediums; with Barnacles, she employed a printmaking technique called lithography, in which a design is drawn directly onto a stone and then affixed with chemicals before it is transferred onto a surface. For this work, Samayualie rendered the barnacles and their surrounding with a flattened sense of space, emphasizing the shape of the organisms’ shell. The image is divided into two distinct fields of color, suggesting the submersion of water or the lapping of waves.

Jar with Floral Design, Camille Bernal

To achieve this vessel’s pale outer coloring, Camille Bernal applied twenty-four layers of white slip to its surface. Bernal creates all her pottery with traditional clay that she processes herself and tempers with volcanic ash. Her designs—like the delicate flowers seen stretching upwards here—are illustrated with natural pigments, some of which are found in the canyons around her home of Taos Pueblo. The blossoms that encircle this pot were painted with an additional three to five layers of plant-based paint, creating a watercolor-like effect with varying degrees of translucency.

The Meeting/The Connection, Troy Sice

In an interview after the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts’s acquisition of The Meeting/The Connection, Troy Sice explained the motivation behind his work and shared the sculpture’s connection to his Zuni heritage: “My vision for the piece is everything Zuni. It has the corn maidens coming out and Kolowisi on the bottom—he is the water dweller. We pray to him for guidance for rain or to find water. As an artist, I envision him going in the water and then coming back out on the other side. The Pueblo [buildings on the bottom] symbolizes us as people. Again, we pray for rain and for abundance. There are rain clouds on the side of the piece that have turquoise and lapis that are also used in pottery designs and then there are dragonfly symbols—[the dragonfly] is not only the water symbol, but he is also the messenger for our prayers to the heavens and the gods. When we pray, dragonfly is the one who takes our prayers and delivers them to our ancestors…”

Puttawus, Raven Custalow

Raven Custalow is a Mattaponi tribal citizen and CEO of Eastern Woodland Revitalization, an organization whose mission is to revitalize cultural practices specific to Eastern Woodland Indigenous tribes. Puttawus, a feather mantle created by Custalow, embodies Indigenous revitalization and resurgence, a concept that refers to Indigenous people reclaiming elements of their cultural identity that were repressed, stolen, or prohibited by colonization. Prior to the arrival of Europeans, many Eastern Woodlands tribes made and wore feather mantles in a range of styles. Over time, forced assimilation compelled Indigenous peoples to hide or forgo their languages, ceremonies, traditional clothing, and cultural practices for their own protection, resulting in some ancestral creative traditions waning. Today, artists like Custalow are figuring out new ways to assert these traditions; according to Custalow, when she became curious about constructing feather mantles, “I [didn’t] have the knowledge of the exact technique that my people used, but I was able to research and create my own way of doing it….That’s who we are as Indigenous people. Things evolve over time. We learn new ways.”

Large Pot, Christine Custalow

Christine Custalow is descended from both Rappahannock and Mattaponi peoples. She learned pottery making from her mother and continues to create works with the same traditional methods. Her low-fire “baking” process results in rich, luminous surfaces with organic tonal variation. Custalow uses the pinch-pot building process for smaller vessels and the coil method for larger ones. Most of her pots are burnished to a high shine using a smooth rock or a small piece of deer antler as a polishing tool. Custalow also employs other methods of surface embellishment. This example uses decorative elements such as feathers and beads attached to the vessel after it has been fully fired.

Artist Videos

Artist Profile: Jeremy Frey

3:59Discover the art of basket weaving with Jeremy Frey, who is known for his unique designs and his use of traditional and contemporary materials.

Artist Interview and Performance: Raven Custalow

4:01In 2020, Raven Custalow, Virginia Native artist of Mattaponi and Rappahannock ancestry and an enrolled member of the Mattaponi tribe, was commissioned by VMFA to create a feather-mantle titled Puttawus. This video shows the artist at work and performing while wearing the feather-mantle.

Artist Talk: Raven Custalow

57:36In 2020, Raven Custalow, Virginia Native artist of Mattaponi and Rappahannock ancestry and an enrolled member of the Mattaponi tribe, was commissioned by VMFA to create a feather-mantle titled Puttawus. Featured here is a discussion about the work and the artist’s practice with Dr. Johanna Minich.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Discover more ways to connect with the art by Native American Artists on Learn.