First Peoples

For thousands of years, native peoples lived in the region of present-day Richmond, sustained by plentiful natural resources along the banks of the James River. At the time of the earliest English landfall and settlement in the 17th century, this site stood at the western perimeter of the chiefdom of Powhatan made up of a broad alliance of Algonquin speaking tribes.

Colonial, Early Republic, and Antebellum Eras

By the mid-1600s, when the Powhatan peoples had been weakened by treaty and war, the English laid claim to the territory as part of its expanding colony. In 1679, the Virginia Assembly gave this region as part of several land grants to William Byrd, a successful Indian trader who formed the Henrico Militia. Adding to the considerable property he had inherited and acquired, he bequeathed close to 30,000 acres to his son, William Byrd II, who helped lay out the street plan for the city of Richmond. His heir, William Byrd III, sold extensive parcels of land in a 1769 lottery.

By the early 19th century, the property had changed hands various times and, in 1815, became part of the speculative development of the Town of Sydney (primarily today’s Fan District). The scheme failed during a real estate crash shortly afterwards. Banker and city resident Anthony Robinson Jr. purchased 190 acres of the Sydney parcels in the late 1820s through the 1850s, including the property on which VMFA now stands. He named his country seat “The Grove” for its large stand of old-growth oaks.

The estate, comprised of woods and open countryside, was cultivated through the labor of enslaved African Americans. While the number of people owned by Robinson varied over time, an 1860 slave schedule lists a dozen living at The Grove. The multigenerational community—ranging in age from one to sixty years-old—was housed in two cabins to the west of the mansion.

Robinson House

The earliest Robinson dwelling, built ca. 1828 on this site, began as a modest summer house. After an elaborate enlargement of the building in 1856-1857, Anthony and his wife, Rebecca, took up year-round residency at The Grove. The renovated two-story mansion featured characteristics of the fashionable Italian Villa style with Renaissance-patterned window trim.

Anthony died in 1861, just a few months after the beginning of the Civil War. After the fall of Richmond and the end of the war in April 1865, the widowed Rebecca invited Union officers to use the house as a headquarters as protection against possible looting. In 1884 the couple’s son Channing sold the residence and thirty-six surrounding acres to the newly formed R. E. Lee Camp, No. 1, Confederate Veterans. After the organization sold some parcels east of Clover Street (now the Boulevard), the 24-acre property was bounded by the Boulevard, Grove Avenue, Sheppard Street, and Kensington Avenue.

R. E. Lee Camp Confederate Soldiers’ Home

Between 1885 and 1941, the R. E. Lee Camp Confederate Soldiers’ Home—a large residential complex for poor and infirm southern veterans of the Civil War—stood on this site. Founded by R. E. Lee Camp, No. 1, Confederate Veterans, the facility was built with private funds, including donations from former Confederate and Union soldiers alike. At peak occupancy, residents numbered just over three hundred. By the time the soldiers’ home closed, a total of nearly three thousand veterans from thirty-three states had called the place home.

In 1886, Robinson House—renamed Fleming Hall during the soldiers’ home era—gained a third floor and belvedere. For the next half century, it served as the compound’s administration building and war museum. After the facility’s closing, the commonwealth granted use of the building to the Virginia Institute for Scientific Research (1949-1963), and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (1964 to the present).

Today, Robinson House is undergoing renovations. When it reopens in 2019, it will house a regional tourism center, history exhibition, and offices.

Robinson House before current renovations. Photo: VMFA, Travis Fullerton.

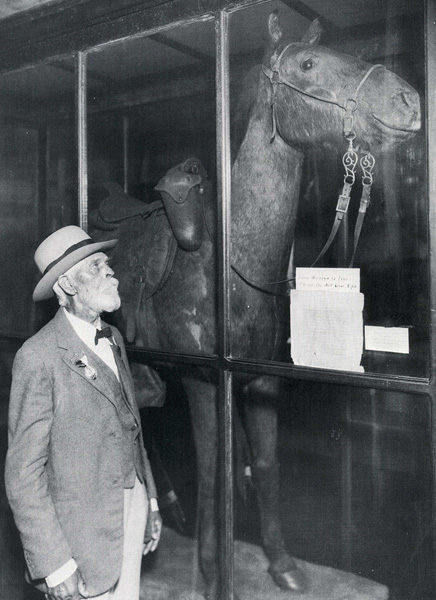

A favorite attraction in the soldier’s home museum was Stonewall Jackson’s war horse, Little Sorrel, who died at the compound in 1886. The horse’s preserved and mounted hide was on display—as seen in this 1932 photograph alongside veteran J. C. Smith—until its move in 1948 to the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington. It remains on view at VMI today. Photo: Dementi-Foster Studios.

The green space in the central grounds of today’s VMFA property was once the commons of the soldiers’ home. Around the oak-filled park stood the administration building, barracks, dining hall, hospital, recreation hall, steam plant, and assorted outbuildings. The superintendent’s house, nine residential cottages, and a chapel formed an arc to the west. With the exception of Robinson House, the Confederate Memorial Chapel, and a utility shed, the remaining structures were demolished or moved between 1935 and 1941.

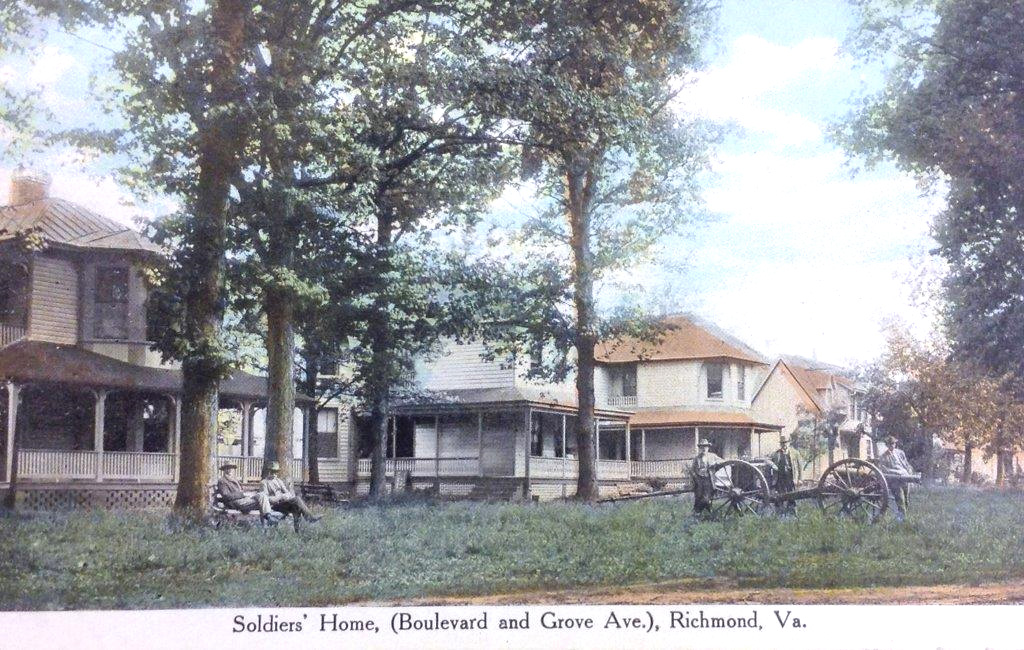

A postcard view of the residential cottages, ca. 1910. VMFA Library.

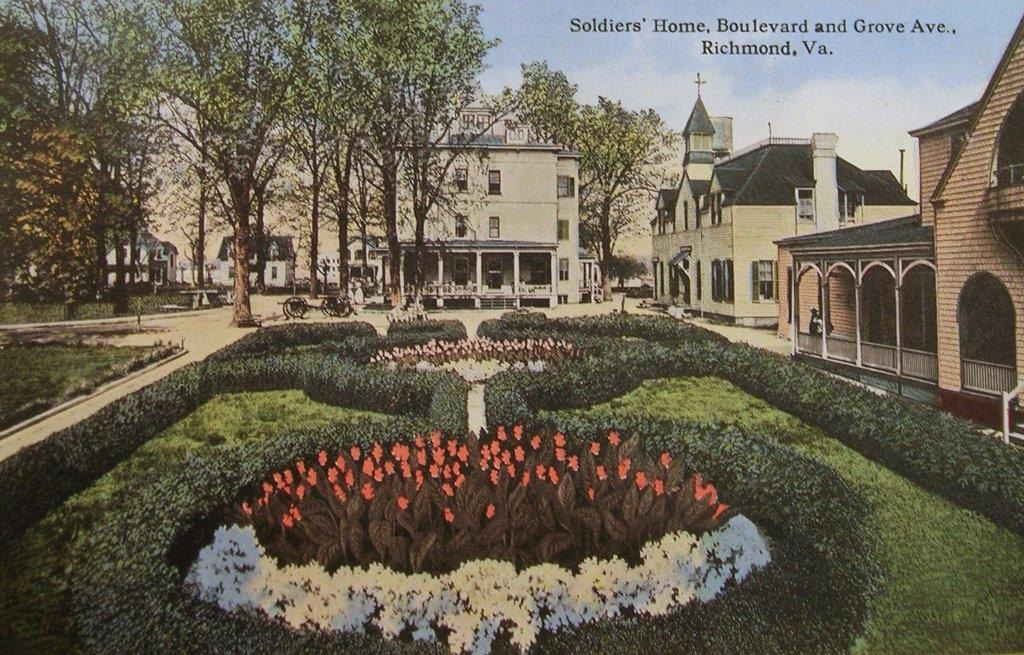

This view of Robinson House, seen from the east in a postcard dated 1914, pictures the soldiers’ home hospital (far right) and Pegram Hall (center right) during the facility’s heyday. VMFA Library.

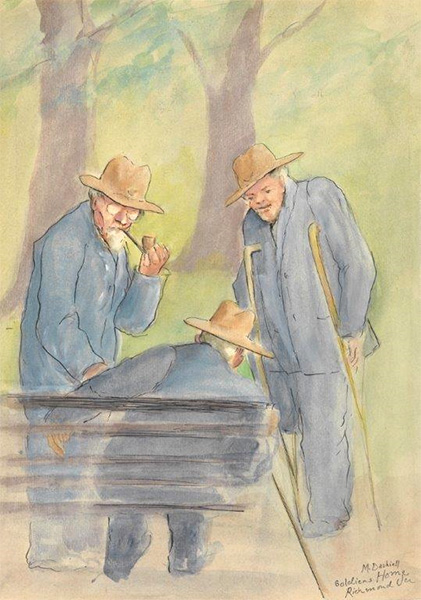

In the 1920s and 1930s, Richmonder Margaret May Dashiell made numerous sketches of camp residents, including this threesome engaged in conversation. VMFA, Gift of Mrs. William A. Archer.

For residents, life revolved around a semi-military routine of drills, chores, and inspection. Leisure activities included storytelling and card playing, as well as occasional lectures, musicales, and visits from schoolchildren. In 1904 resident Benjamin J. Rogers described the camp as a “home in the true sense,” noting:

Our rooms are furnished with two single iron bedsteads . . . a good mattress, bureau, washstand, pitcher and bowl, and two chambers. We are required to sweep them out every morning and carry out our slops. . . . They give us a hat, over coat, full suit of uniform, four pair shoes a year, soap, tobacco, chewing or smoking . . . undershirts and drawers, top shirts . . . socks, towels and color handkerchiefs.

Veterans demonstrate battery formations near their cottages in this early-20th-century photograph. Several Napoleon twelve-pounder artillery pieces were once displayed on the grounds. Photo: Cook Collection, The Valentine.

This postcard view pictures the original entrance of the soldiers’ home accessed from Grove Avenue. Carriages—and later automobiles—entered and proceeded north around a large oval drive to access the various buildings, including Robinson House (then called Fleming Hall) at the opposite end. Photo: Special Collections and Archives, James Branch Cabell Library, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Over time, members of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR., Union veterans’ organizations) donated substantial funds, furnishings, and medical supplies to the soldiers’ home. The site became a favorite venue for joint “Blue and Gray” reunions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Members of R. E. Lee Camp, No. 1, pose alongside visiting Union veterans from Lander Post, No. 5, G.A.R., of Lynn, Massachusetts, near Robinson House on July 5, 1887. Photo: Library of Virginia.

Confederate Memorial Chapel. Photo: VMFA, Travis Fullerton.

Confederate Memorial Chapel

Dedicated in 1887 to the Confederate war dead, the nondenominational chapel—still standing on the southwestern corner of the museum grounds—served as a place of worship for the residents of the soldiers’ home. Funded by donations from veterans and private citizens, it was designed by architect Marion J. Dimmock in the Carpenter-Gothic style. The interior features hand-hewn pews, eight commemorative stained-glass windows, and a bell that once tolled the day’s hours. By the time the home closed fifty-four years later, the chapel had hosted approximately 1,700 funeral services for the former soldiers.

Today owned and maintained by VMFA, the chapel is open daily to visitors, free of charge.

20th-Century Transitions

From the facility’s earliest years, the Commonwealth of Virginia helped fund the soldiers’ home. In 1892, Lee Camp agreed that, in return for growing state subsidies, it would relinquish the deed to the property “when it ceases to be used for present purposes.” Over the next four decades, the Act of 1892 was revisited and amended several times to increase funding and delay the property transfer. When the last resident died in 1941, the commonwealth gained full ownership of the site. By that time, the surrounding grounds had been designated as the Confederate Memorial Park.

Throughout the early 20th century, Lee Camp administrators and the commonwealth granted parcels of land for other structures: Confederate Memorial Institute (1913, “Battle Abbey,” later absorbed by the Virginia Historical Society); Home for Confederate Women (1932); Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (1936); and the Memorial Building—national headquarters of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (1957).

] Funded through private donations and state support, the Home for Confederate Women was designed by architect Merrill Lee, who was inspired by the neoclassical lines and motifs of the White House. Its soaring ionic portico faces Sheppard Street. Photo: VMFA, Travis Fullerton.

Home for Confederate Women

The monumental limestone building on the west boundary of the present museum grounds was built in 1932 as a residence for destitute female relatives of Confederate veterans. In operation for over fifty years, the home was closed by its board in 1989. Assuming ownership of the building, the Commonwealth of Virginia designated it as a memorial to the women of the South and transferred its care to VMFA. Today, renovated and renamed the Stan and Dorothy Pauley Center, it houses museum offices and meeting rooms as well as the headquarters of the Virginia Association of Museums.

VMFA Today

From 1936—the time of the opening of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts—to the early decades of the 21st century, the museum has undergone five significant expansions, culminating in the 2010 opening of the James W. and Frances G. McGlothlin Wing.

Having recently marked its 80th anniversary, VMFA celebrates not only its history and accomplishments as one of the nation’s leading comprehensive art museums but also commemorates the compelling and important history of its grounds. This includes the ongoing, careful stewardship of Robinson House, Home for Confederate Women (Pauley Center), and the Confederate Memorial Chapel—all three structures named to the prestigious Virginia Historic Landmarks and National Register of Historic Places listings.