The Classical Past: Rome

Why do we remember the grandeur that was Rome? This resource illustrates and investigates the countless ways that the art, literature, language, and traditions of ancient Rome have inspired and guided the development of Western culture.

The Classical Past: Rome can be paired with The Classical Past: Greece to help students compare and contrast the two civilizations. These resources were developed with parallel themes:

Greece Rome

Who were the Greeks? Who were the Romans?

A Celebration of Ideas Public Life an Portraiture

Life in Ancient Greece Life in Ancient Rome

Gods, Goddesses and Homer Gods, Temples, & Deities

The First Plays Literature, Comedy & Spectacle

The Hellenistic World The Roman Empire & Beyond

Who Were the Ancient Romans?

Citizenship

Romans did not necessarily live in the city of Rome. At its height, the empire stretched from Mesopotamia to Scotland and from Romania to Morocco. Nor did language define a Roman. Latin was the primary tongue of the city of Rome, but Greek was spoken throughout the empire, alongside hundreds of local languages and dialects. It was citizenship, which could be awarded to any male in the empire (including slaves), that set Romans and their families apart from other inhabitants of the ancient world. A Roman was a citizen of Rome.

Founding Rome

According to legend, Romulus founded Rome on April 21, 753 BC. Romulus and his twin brother Remus were sons of the god Mars. Their ambitious great-uncle usurped their grandfather’s throne and ordered the deaths of Romulus and Remus. A she-wolf rescued and nurtured the twins, as illustrated on this coin. The she-wolf became an icon for the city of Rome.

Romulus and Remus also claimed descent from the Trojan hero Aeneas, who was the son of Venus (known as Aphrodite in Greece). This connection gave Venus special status among the deities of Rome.

From Republic to Empire

In 509 BC, the Roman Republic was established and over the next few centuries gained control of the Italian mainland. Following a series of civil wars, Julius Caesar’s adopted son Octavian consolidated control over the expanding Roman Empire and received the title of Augustus from the Senate in 27 BC. Augustus became the first Emperor of Rome, officially ending the Roman Republic. He died in 14 AD and the era of peace he established lasted for more than 200 years.

Rome’s Legacy

Romans remade the Western world during their thousand year history. They developed sophisticated administrative practices and significant bodies of law, revolutionized military organization, urbanized many parts of the ancient world, and influenced the development Western culture. Latin continued to serve as the international language of science, scholarship, and diplomacy throughout most of Europe into the 1800s.

The Pax Romana, the long period of relative peace initiated by Augustus, ended with the death of Emperor Marcus Aurelius in 180 AD, who is shown on this coin, called a denarius. On the back, Pax (peace) stands holding an olive branch and a cornucopia.

Public Life & Portraiture

To the last days of the empire, Roman citizens acknowledged the central authority of the government—and every inhabitant of the empire understood his position within the hierarchy. Roman engineers may have constructed roads throughout the Roman world, but every road led back to Rome.

The ideal Roman citizen was disciplined, courageous, dutiful, practical, and loyal to Rome, and Roman leaders cultivated public images that conformed to these characteristics. While Greek artists had celebrated the ideal human form, Roman artists excelled at portraits designed to project specific ideas about the subject’s authority and status. An official portrait template was developed for each emperor to convey his lineage and power. In this portrait, Caligula wears a toga, the official garment of a Roman citizen. The toga was painted in antiquity and the color signified his important rank. The toga would have been either all purple, or white with a purple border. Each communicated a different message.

The image of the emperor was also disseminated on coins that were minted and circulated throughout the provinces. This denarius features a portrait of the emperor Augustus. Statues of the emperor were often placed in temples. Statues and portraits on coins were the only way most people in the Empire saw what their leader looked like.

This follis (coin) was issued by Constantine the Great who, in 313 AD, issued the Edict of Milan, a proclamation that granted tolerance to all religions, including Christianity. Some years later, in 330 AD, he moved the capital of Rome to Byzantium, which was later renamed Constantinople in his honor.

Life in Ancient Rome

Professions

In the early days of the Republic, many Romans were farmers. Although rich soil was scarce throughout the Italian mainland, the Tiber River valley produced a variety of crops including grapes and olives, and grain grew particularly well along the Po River. Later, citizens and freedmen often turned to specialized professions, such as wine and olive oil production, shipbuilding, and the sale of luxury goods and commodities.

In this 1st-century marble relief, a potter works at his trade while his wife makes bread, a staple food in ancient Rome.

Warfare

The army was the means by which Rome expanded and controlled its territory, and military service served as a critical step in acquiring political power. Mars, the god of war, is featured on this coin issued by Emperor Caracalla, son of Septimius Severus.

Dress

This bust is a portrait of Agrippina, the Emperor Caligula’s mother. Roman women usually wore tunics. If they were married, they also wore long pleated dresses called stolas over their tunics. You can see these on the woman holding bread in the Relief of a Potter and his Wife. Elaborate hairstyles like Agrippina’s showed wealth and status.

Roman Baths

A central feature of a Roman city was the public bath complex, visited daily by all classes and ages. Water for these architectural wonders was supplied by aqueducts, a Roman invention. An image of women bathing decorates the back of this Roman mirror.

Villas of the Wealthy

Affluent Romans often lived in lavish villas decorated with colorful frescoes on the walls and mosaics on the floor. This mosaic represents the four seasons and was found near Antioch, a Roman city in the province of Syria.

The Four Seasons, section of floor mosaic from the House of the Drinking Contest, Roman (Antioch, Roman province of Syria), 250-300 AD, Stone and glass tesserae, Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 51.13

Gods, Temples & Deities

The public and private Roman belief systems were varied and complex. Each Roman home had a lararium, a kind of miniature temple dedicated to the lares, the household gods that protected the home and family. Offerings to lares were made in gratitude for this protection.

The Romans also worshipped many gods in public temples and at festivals. Offerings were dedicated at the temples, and each temple housed a cult image of the god or goddess it served.

This larger-than-life head of Dionysus may have come from one of his cult temples. In Rome, Dionysus (also called Liber Pater or Bacchus) was a god of fertility, wine, and theatre.

As Roman territory expanded, many foreign religions gained popularity among Romans.

The cult of the Apis Bull, which originated in Egypt, was one such religion. The bull was associated with Osiris, the god of the underworld and vegetation.

Mithras was an ancient Indo-Iranian god whose cult became extremely popular in the Roman military beginning in the 2nd century AD. Small groups of male initiates gathered in cavelike shrines to worship in front of images like this relief that shows Mithras slaying the bull.

Literature, Comedy & Spectacle

Romans absorbed and adapted many aspects of Greek literature and culture, focusing on forms that suited Roman tastes and purposes. They also broke new ground in the areas of spectacle, comedy, and satire.

Spectacle

Romans had a taste for theatrical spectacles, including gladiatorial combats, staged naval battles, animal hunts, and chariot racing. Rome had four racing companies that were named for the colors their charioteers wore: red, white, blue, and green. This denarius shows a four-horse chariot.

Epic

Virgil wrote his remarkable epic poem, The Aeneid, in conscious imitation of the Greek Homeric epics to provide Rome with a suitably inspiring foundation myth. The story connects the Trojan hero Aeneas, son of the goddess Venus, with the family of Julius Caesar and the Emperor Augustus.

Poetry

Romans also produced poetic masterpieces, including Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a work about interactions between mortals and gods. In one poem, Minerva, the goddess of wisdom and handcrafts, transforms a woman into a spider for daring to compare her skill as a weaver with Minerva’s.

This Byzantine weight shows Minerva wearing the helmet of a warrior.

Theatre

The comedies of Plautus are among the earliest Roman literary works to survive in their complete form. Plautus adapted many Greek plays, creating farces with stock characters who made scathing comments on current events.

Many Roman comedies included scenes with mimes, who might have resembled these South Italian funerary pieces.

Dionysus, the god of theater, was also associated with death. Both of these aspects of the god are seen in this sarcophagus, which features erotes (cupids) playing the roles of Dionysus, Castor and Pollux, and Heracles in various festivals and processions.

Satire

Roman writers excelled at satire, a genre of literature that ridicules human weaknesses and the social ambitions. The orator Quintillian described satire as “a wholly Roman phenomenon.” The most famous Roman satirists were Horace, Martial, and Juvenal.

The Roman Empire & Beyond

Although the last emperor of Rome was deposed in 476 AD, the influence of Rome has echoed through centuries of Western culture. Modern political structures, legal systems, medical terms, place names, literary forms, art, architecture, and history have their roots in Rome.

Inspiring the Western World

Enthusiasm for the Classical world has inspired many artists, writers, and scholars. On this 17th-century ginger jar, an English silversmith pictures Aeneas rescuing the lares and penates (his household gods) as he escaped the final carnage of Troy with his family and followers.

In the 18th century, the philosophers, artists, and writers of the Enlightenment celebrated a rebirth of Classical themes and images. This Neoclassical painting shows Cornelia, the embodiment of Roman female virtue.

Across the Atlantic, Roman influences appear often in American culture. This exquisite 19th-century neoclassical sculpture by William Wetmore Story was inspired by the story of Cleopatra, the last queen of Egypt.

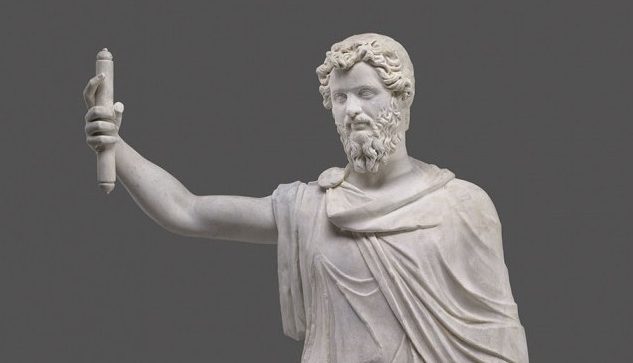

The signs and symbols of Rome have become the emblems of Western institutions and nations. This sculpture of Zeus Serapis is surmounted by an eagle—a powerful symbol of Roman strength. Western rulers, from Russian Tsars and German Kaisers to the founders of the United States, have incorporated the eagle into their insignias to associate themselves with Rome.

Closer to home, Virginia’s state capital is crowned with a Roman-style dome, the U.S. Senate is named for its Roman precursor; and the seal of the United States bears the Latin words e pluribus unum (out of many, one), which were penned by Virgil in ancient Rome.

Learn about the restoration of a Roman statue!

Septimius Severus Conservation

6:26In 1967 the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts acquired a monumental statue of the Roman emperor Septimius Severus. In 2007 the museum undertook a comprehensive research campaign using scientific and art historical methods to determine whether or not the statue is a work of ancient art.