A Guide to Impressionism

Learn about the history and artistic style of the Impressionists in this teacher’s resource. Find out why the Impressionists were considered so shocking and how they have influenced art over a hundred years later. Explore the art of Monet, Renoir, Degas, and more!

The Shocking New Art Movement

The word “impressionism” makes most people think of beautiful, sunlit paintings of the French countryside; glorious gardens and lily ponds; and fashionable Parisians enjoying life in charming cafes. But in 1874, when the men and women who came to be known as the Impressionists first exhibited their work, their style of painting was considered shocking and outrageous by all but the most forward-thinking viewers. Why did these young artists cause such an uproar? The following comparison shows how their radical ideas, techniques, and subjects broke the time-honored rules and traditions of art in late 19th-century France.

“What do we see in the work of these men? Nothing but defiance, almost an insult to the tastes and intelligence of the public.” -Etienne Carjat, “L’exposition du bouldevard des Capucines,” Le Patriote Francais (1874)

“There is little doubt that Impressionist landscape paintings are the most…appreciated works of art ever produced.” –Richard Brettell and Scott Schaefer, A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape

The Judgment of Paris

François-Xavier Fabre, 1808

Oil on canvass

Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund

The accepted style of painting often featured:

- Great historical subjects or mythological scenes that were meant to be morally uplifting;

- An emphasis on line, filled in with color;

- Smooth, almost invisible brushstrokes;

- Paintings primarily done in the artist’s studio

The Watering Pond at Marly with Hoarfrost (L’Abreuvoir à Marly – gelée blanche),

Alfred Sisley, 1876

Oil on canvass

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

Impressionist style of painting often featured:

- Ordinary subjects from everyday life;

- An emphasis on color, lines, “dissolved”;

- Highly visible brushstrokes referred to as “painterly”;

- Paintings completed outdoors or en plein air.

Challenging the Establishment

What happened to artists who dared to challenge established tastes and standards? Many of them found that their work was not accepted for display at the government-sanctioned, annual Paris Salon, the most important art show of the time. Acceptance by the Salon was critical to those hoping to achieve success and sell their work.

As seen in the image below, thousands of artists competed for entry into this distinguished exhibition, subjecting their work to the scrutiny of a small committee of judges that had the power not only to accept or reject a painting but to rank it as well. If each member of the committee approved a work, it was accepted for display and hung “on the line,” hanging at the ideal viewing height in the gallery. Works receiving fewer positive votes were placed in the less advantageous positions. Indeed, they might be “skyed,” placed so close to the ceiling that viewing them was virtually impossible. The works that were turned down were stamped on the back with a red R—meaning refusé. This humiliating badge of rejection made it more difficult for the artist to sell the painting to a private buyer. All in all, artists typically had about a fifty-fifty chance of being accepted. In 1863, those odds dropped significantly, when only 988 artists were accepted out of three thousand. With artists’ livelihoods depending to such a large degree on Salon acceptance, frustration with the judging hit an all-time high and reached the ears of the emperor.

The 1863 Salon de Refusés

After so many artists were rejected from the Salon competition of 1863, Napoleon III stepped in to still the outcry. He ordered a separate exhibition of the rejected works that came to be called the Salon des Refusés. It drew a crowd of seven thousand people on the first day alone. One of the works displayed was Édouard Manet’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe, today considered one of art history’s most important paintings. The depiction of two filly dressed men with a nude woman in a contemporary setting shocked traditional critics and viewers, especially since the figures were identifiable. Younger critics, however recognized Le déjeuner sur l’herbe as a manifesto of artistic freedom granting painters the authority to create according to their own sensibilities rather than blindly follow accepted modes representation.

A New Society of Artists

The majority of artists continued to struggle for acceptance into the Salon in the years following the famous 1863 Salon des Refusés—the Impressionists among them. But while they wanted the recognition and financial stability the Salon’s approval could offer, they also wanted to pursue new ways of painting. As a result, their works were often returned, stamped with the infamous red R.

In 1874, determined to make the public aware of their art, the Impressionists organized their own exhibition separate from the Salon. A year earlier, the group took the unprecedented step of forming a private, independent association of artists called Société anonyme des artistes, peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs, etc. (Anonymous society of artists, painters, sculptors, and printmakers). The decision to hold an exhibition that was essentially a capitalistic enterprise was a bold one in many ways. Unlike the multitude of artists who exhibited at the Salon, only thirty artists participated in this exhibit, and each could display several works as opposed to the limit of two imposed by the Salon. The works were exhibited in a casual, intimate manner; some were displayed on easels, almost as if the viewers were visiting an artist’s studio. Held in the large, modern, glass-fronted studio of the great French photographer Félix Nadar, the exhibition opened two weeks earlier than the Salon, a tactic chosen to garner advance publicity and negate any notions that the exhibition consisted of rejected works. The strategy worked; the exhibit attracted a great deal of media attention. In fact, it was a journalist, mocking Claude Monet’s painting Impression, Sunrise, who gave the group the name that would later become synonymous with beauty: Impressionism.

Studio of French photographer Félix Nadar located at 35 de Boulevard des Capucines in Paris, site of the first exhibit of Impressionist paintings in 1874.

“The common view that brings these artists together in a group and makes of them a collective force within our disintegrating age is their determination not to aim of perfection, but to be satisfied with a certain general aspect. Once the impression is captured, they declare their role finished…if one wishes to characterize and explain them with a single word, then one would have to coin the word impressionists. They are impressionists in that they do not render a landscape but the sensation produced by the landscape. The word itself has passed into their language: in the catalogue the Sunrise by Monet is called not landscape, but impression. Thus they take leave of reality and enter the realms of idealism.” –Jules-Antoine Castagnary, Le Siècle

A City under Construction, Artists on the Move

Although Paris at mid-century was Europe’s second largest city, its infrastructure was antiquated and inadequate. Unlike London and Berlin, it lacked public systems for water and sewage, sufficient roads, and other urban resources to support its burgeoning population. The first act of the formerly exiled Napoleon III , nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, was to modernize Paris. He appointed Baron Haussmann to mastermind one of the largest urban renewal projects the world had ever seen. Paris became a vast construction site, and much of the city was demolished to make way for wide boulevards and modern buildings. Thousands of people—primarily the working class—were evicted and relegated to degraded and poor suburbs, a decidedly political ploy since Napoleon III considered these neighborhoods hotbeds of left-wing radicals. The family of Pierre-Auguste Renoir was one of those displaced. Their home stood on the site where the Louvre’s central courtyard is located today.

The negative aspects of living in the midst of urban renewal were offset by an exhilarating sense of change and vitality. Modern life in Paris attained a new vibrancy reflected in many Impressionist canvases. Middle-class Parisians enjoyed the increased leisure time made possible by time-saving machines of the Industrial Revolution. The urban delights of the theatre, concerts, and cafés were captured in the new paintings. And if one needed a break from city life, the countryside was now within easy reach.

Artists on the Move

Artists were also on the move, leaving their studios to paint the same landscapes and seascapes their fellow citizens were enjoying. New developments in artists’ equipment—lightweight, portable easels; folding chairs; and especially collapsible metal paint tubes that replaced unwieldy pouches made from pigs’ bladders and prevented paint from drying out—made it easy for artists to paint outdoors. In addition, explorations in the science of color and innovation in photography, the latter still a relatively recent invention, inspired artists to look at the world around them in a new way.

The Beach at Trouville (La Plage de Trouville)

Eugène Boudin, 1864

Oil on panel

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

In Open Air

Advances in transportation made tourism ever easier for the French middle and upper classes. Holidays by the sea were all the rage, and visitors flocked to scenic ports along the coast of the English Channel (referred to as La Manche in France) to take advantage of the healthful sea breezes. They enjoyed the opportunity to see and be seen, as evidenced by the stylish clothing of the vacationers in this painting by Eugène Boudin.

Like artists today, 19th-century painters worked hard to make a living from their art. Boudin’s pictures of fashionable figures on the beach were very popular, no doubt reminding those who bought them of their own seaside excursions. But Boudin’s upbringing and childhood—his father was a seaman and the artist himself spent time as a cabin boy—sometimes made him feel “ashamed at painting the idle rich.”

The subjects that truly captured Boudin’s heart were the ever-changing play of light and clouds billowing across the sky. To capture these fleeting effects, he painted directly from nature using short, rapid brushstrokes to sketch the scene.

Boudin influenced the new generation of artists coming along, especially the young Claude Monet. In fact, Boudin exhibited along with the Impressionists in their groundbreaking exhibition of 1874. Boudin’s unofficial student, Claude Monet, became the driving force in the new style of art. Following Boudin’s example, the passionate young artist began his lifelong love of painting outdoors. Monet later said, “Boudin, with untiring kindness, undertook my education. My eyes were finally opened and I really understood nature; I learned at the same time to love it.”

Like Boudin, Monet used short, quick brushstrokes to convey the rich details in this painting. Although titled Camille at the Window, the work is more than a portrait of the artist’s wife: she becomes, almost, one the flowers he has vigorously depicted.

Camille at the Window, Argentuil (Camille à sa fenêtre, Argenteuil)

Claude Monet, 1873

Oil on canvass

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

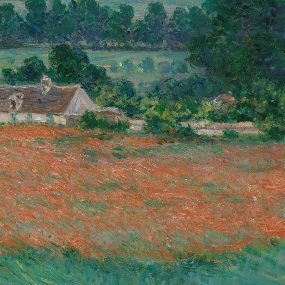

The Science of Color

Field of Poppies, Giverny

Claude Monet, 1885

Oil on canvas

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

Over the next ten years, Monet continued to explore the effects of light on his outdoor subjects. He also began to push the boundaries of what was acceptable treatment of color in his paintings. By the time he completed Field of Poppies, Giverny, the features that would become trademarks of the Impressionist style were in place: bright, contrasting colors; distinctive brushwork; and subjects from daily life painted outdoors.

Scenes from Daily Life and Movement

The son of a tailor and a dressmaker, Pierre-Auguste Renoir spent his teenage years decorating ceramics in a porcelain factory. By 1860, however, he began attending painting classes at the private studio of the Swiss artist Charles Gleyre. Here Renoir became friends with Claude Monet, and soon the two artists were journeying to the countryside to paint directly from nature.

From a technical point of view, both Renoir and Monet painted in the Impressionist style: both used fresh, bright colors applied in short, rapid brushstrokes, and both showed scenes from daily life. But compare Renoir’s Pensive with Monet’s Camille at the Window (both painted at 1870s). How are they different? Renoir’s brushstrokes appear more delicate, almost feathery. More than any painter in the Impressionist group, Renoir focused on people, especially women and children, in quiet, gentle scenes.

Pensive (La Songeuse) or Day Dreaming

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1875

Oil on paper on canvas

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

At the Races: Before the Start

Edgar Degas, ca. 1880-92

Oil on canvas

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

Capturing Movement

Unlike his fellow Impressionists, Edgar Degas preferred to work in his studio rather than outdoors. While Monet and Renoir painted directly on their canvases, Degas more often prepared detailed drawings before he put a brush to his paintings. “No art,” he declared,” is less spontaneous than mine.” But in his choice of modern-day subjects, this serious young artist allied himself with the Impressionist group, joining in almost all of their exhibitions. He was also the most influenced by photography, especially Eadweard Muybridge’s revolutionary work showing the horse in motion that was published in Paris in 1874.

Degas’s At the Races: Before the Start freezes the restless activity of sleek thoroughbreds and their jockeys as they prepare to approach the post. The eye follows the line of horses across the canvas, from the cropped figure on the right to those that ride off into the distance. The colorful silks sparkle in the sunlight against the lush fields of green and gold.

A Modern Woman

Young Woman Watering a Shrub

Berthe Morisot, 1876

Oil on canvas

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

Berthe Morisot was the first woman in the history of French art to be fully accepted as a peer by a group of male artists. A radical idea in itself, Morisot’s inclusion reinforced Impressionism as a art movement for modern life. As a well-bred young woman from a successful bourgeois family, it would not have been unusual for her to pursue painting as a hobby. She studied under Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and other instructors, but her art took a decidedly serious turn under the influence of her friend Édouard Manet. At the time it was very difficult for women of her rank to pursue careers other than marriage and motherhood, but Moristot managed to accomplish all three. She married Manet’s brother, had a child, and exhibited in all but one of the eight Impressionist exhibitions.

Morisot specialized in depicting modern life as lived by women like her. Her subjects tend to be members of her family or close friends, not unusual since young women, even married women, were limited in their excursions to public places and were always chaperoned.

The woman in this painting has just stepped outside to water a plant in a jardinière. She lifts the hem of her white house gown to keep it clean. The loose brushwork is characteristic of Morisot’s desire to capture the subject with as few strokes as possible. While some critics objected to this economy of brushwork, others praised her spontaneity and delicate sense of color—once compared to crushed jewels and flower petals.

New Directions

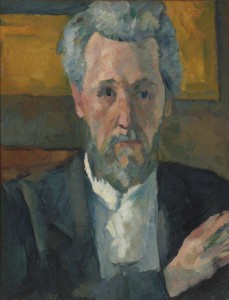

The Impressionists painters, though united in many aspects, maintained their individuality as artists throughout their careers. Their influence guided a generation of painters who followed the paths established by the Impressionists and then forged new direction of their own. For example, beneath the painterly surface of Paul Cézanne’s 1877 portrait of Victor Chocquet, there is an underlying structure based on geometric shapes that would later revolutionize how artists understood and portrayed the world. Vincent van Gogh’s energetic, expressive brushwork in Wheat Field behind St. Paul’s Hospital, Saint Rémy, reflects an Impressionist heritage but speaks more to an inner reality of mind and spirit than an outward representation of the land.

The Impressionists’ revolutionary way of looking at, depicting, and understanding the world forever changed the course of art, opening doors to ever-diverse means of artistic expressions in response to an ever-changing modern society.

Victor Chocquet

Paul Cézanne, ca. 1877

Oil on canvas

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

The Wheat Field behind St. Paul’s Hospital, St. Rémy

Vincent Willem Van Gogh, 1889

Oil on canvas

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon