Introduction

Show Transcript

Search for art, find what you are looking for in the museum and much more.

Animals have long been represented in art. They have been portrayed as representations of gods and goddesses, symbolically in religious art, and as pets or part of everyday life. Some of the earliest art known to man were animals painted on walls of caves. Join us as we explore 4 works of art in VMFA’s permanent collection that were inspired by animals.

Animals have long been represented in art. They have been portrayed as representations of gods and goddesses, symbolically in religious art, and as pets or part of everyday life. Some of the earliest art known to man were animals painted on walls of caves. Join us as we explore 4 works of art in VMFA’s permanent collection that were inspired by animals.

Imperial Tsarevich Easter Egg made by the Faberge Firm, Work master – Henrik Wigström – made in 1912

Egg – 4 7/8″ X 3 9/16″/ miniature – 3 3/4″ X 2 3/8″ / Stand – 2 5/8″ X 4 1/8”

The egg is made of lapis lazuli, gold, diamonds The Miniature is made of silver, platinum, lapis lazuli, diamonds, watercolor on

ivory, rock crystal

The Imperial Tsarevich Easter Egg was presented by Tsar Nicholas II to his wife, Empress

Alexandra Feodorovna, in 1912. The egg is cleverly constructed to appear as if it is carved from a single piece of lapis lazuli. It actually has six lapis lazuli sections. The joints are concealed under the elaborate gold decorations that include double-headed eagles, a symbol of imperial Russia. The top of the egg is set with a table diamond (a thin, flat diamond) that covers the Cyrillic monogram AF (for Alexandra Feodorovna) and the date 1912.

This imperial egg is about the size of a softball, if softballs were oblong instead of spherical. The lapis lazuli stone it is carved from is a dark, electric blue so vibrant that it almost appears to glow. The surface of the stone has tiny golden flecks and spidery black and gold veins that would be very easy to overlook if you didn’t know they were there.

Exquisite designs cover the egg almost as if it were tightly ensnared in a perfectly embroidered lace, except instead of lace, these designs are made of gold. With the high contrast of luminescent gold against electric blue, every precise, golden detail seems to radiate toward the viewer. Looking at it is like diving into clear, cool water on a 100 degree day; the moment the heat of your body meets the coolness of the water there is a refreshing, sharp clarity.

Let’s take a closer look at the gold designs. Interlocking lines and spirals make up the lacey designs at the top and bottom of the egg. These transition into flowers and vines as they weave seamlessly into a more figurative pattern that wraps around the egg’s middle. This figurative pattern alternates effortlessly between two decorative forms.

One of the forms is a very small bust of a boy. Coming up from his shoulders are dragonfly-looking wings. His body tapers down from the chest like a long sword and plummets straight into the open petals of a lily-like flower. A tiny flower garland, starting on either side of the boy’s wings, drapes evenly across the center of his sword-shaped body.

The second form in this pattern is the double-headed eagle. Its puffed chest and outstretched wings face forward as its two heads, a crown hovering just above them, look off to opposite sides. Directly above the crowned eagle is an elaborate chandelier flanked on either side by two smaller, lower hanging chandeliers. Flowery vines climb gracefully up through the middle of the egg to delicately connect with the smaller chandeliers and to act as decorative dividers between the eagle and the boy.

The egg, with its smaller end down, sits straight and tall on an elegant, three-legged gold stand. The stand rests on top of a mirror which allows viewers to see the flat diamond that punctuates the very bottom of the egg.

Despite appearing to be made of a solid piece of lapis lazuli, the egg is actually hollow. Around the top third of the egg is a seam and hinge carefully disguised by the gold designs. This allows the top to open and a picture frame, once hidden inside, to be revealed. That picture frame now sits on display beside the egg. Made of platinum with a small lapis lazuli base, the frame is in the shape of the double-headed eagle that appears on the outside of the egg, except that this eagle holds a scepter in one claw and a globe in the other. The front and backside of the frame are completely encrusted with diamonds. Where the body of the eagle would be, there is an oval, two-sided portrait of a young boy. One side shows his face, and the other side shows the back of his head. This young boy, whose picture is encased in such extravagance, was the heir to Imperial Russia.

Jaguar made by an unknown artists between 100 AD and 800 AD

Overall size: 1 1/4 × 4 1/4 in. (3.175 × 10.795 cm)

Made of gold, and modern green stones

Because jaguars could easily cross boundaries by walking on land, swimming in water, and climbing up trees, they were thought to be able to move between realms like a shaman, a priest that transcended the boundaries between life and death, the natural and the supernatural. Only the most potent shamans could transform themselves into jaguars. The gold jaguars in this case may represent transformed shamans because of their male genitalia. Ferocious hunters of animals and humans alike, jaguars symbolized warriors and warfare for those who strove to achieve jaguar-like prowess. An attacking jaguar aims for its prey’s head and neck, an attribute that resonated with the Moche warriors who beheaded their victims.

This gold sculpture of a jaguar is small enough to rest comfortably in your open hand. It has a subtlety to its design, and this, combined with its petite size, can make it easy to overlook the sculpture’s rich detail.

Let’s start with the overall pose of the jaguar. At first glance, it appears to be laying on its belly in relaxation. However, with a closer look, the pose seems less relaxing and more like that of a stalking cat about to pounce. It is poised, balanced, and alert. The back legs, bent and evenly placed on either side of the jaguar’s slim body, seem ready to spring into action. The front legs are tucked into its chest while the front paws sit just below the head in equal alignment with its shoulders, perfectly positioned to enable a quick, strong launch forward. The jaguar’s head is raised with a tiny upward tilt of the chin, and its neck is extended forward like it just caught the scent of something. Mouth partially open, Its lips seem to curl up towards its nose in a snarling grin. Adding to its heightened awareness, the jaguar’s right ear stands erect while the left is slightly bent at the top as if intensely listening. Then there is the tail, which communicates a sense of anticipation as it follows the line of the jaguar’s spine straight out behind its body. Hovering off the ground in this straight line, just the tip of the tail flicks upward.

Let’s shift our focus to the jaguar’s stylistic details. Seam lines along the lower part of the jaguar’s body, as well as around the ears, front paws, and tail, suggest that it was assembled from multiple pieces of gold. On the jaguar’s back, the smoothness of the gold is subtly interrupted by indented, oval-like designs that give the impression of a jaguar’s spotted coat. Indented lines can also be seen on the paws to designate claws and on the face to define the cat’s broad nose and create the upward snarl of the lip. The only thing not made of gold are the eyes. Instead, they are represented by two beautiful, milky green stones that look like they could glow in the dark, mirroring the way a cat’s eyes gleam in the night. Finally, and perhaps easiest to miss, there are two very small holes located near the middle of the jaguar’s tail. It is thought that these holes were used to string the jaguar on a necklace most likely worn by a Moche warrior.

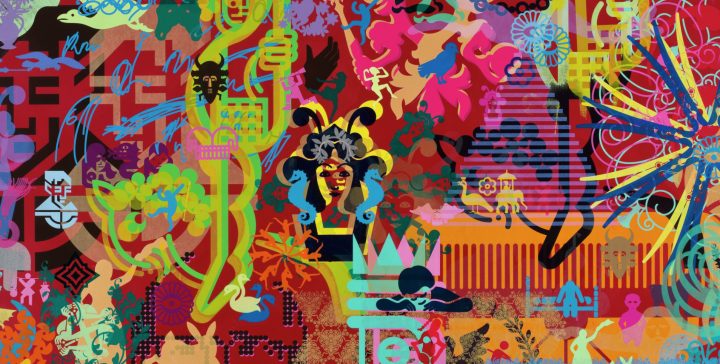

Butterfly Whorl made by Susan Point in 2017

50″ X 2″ (approx 4 ft. in diameter)

Made of Red cedar, copper, pigment

This piece is inspired by a spindle whorl, which is a small disk, often made of wood, used on spinning wheels to help control the speed of the spin. While actual spindle whorls are small enough that you could fit several in your hand at one time, this decorative whorl is just over four feet in diameter. Despite the size difference, this whorl, like many spindle whorls, is marked with designs. Its surface is carved and painted in a mesmerizing labyrinth of detail.

Along the farthest edge of the whorl are two rings that act as a border, enclosing the intertwining designs in the middle. The outermost ring is painted black, and the ring just inside of that is the natural color of the red cedar the whorl is carved from. Both rings are just under an inch wide.

The details within this border can easily send your eyes spinning in different directions, but in time, the image of an abstracted butterfly starts to draw focus. Once noticed, it seems strange that it wasn’t immediately recognized. This butterfly takes up the majority of the inside design; its four wingtips expand to touch the red cedar border ring. Its predominant colors of light green and pale yellow make it pop against the darker accents of brown, black, and brownish red. The butterfly’s wings connect at the very center of the whorl, and a rounded yellow shape peeps out just above their meeting point to represent the butterfly’s head. Two black antenna lines spring out of this yellow head. One antenna bends in an arc to the left, and the other bends to the right.

Four reddish brown shapes, outlined in black, are padded between the butterfly and the border. At the top of the whorl is a thick M-like shape. Its two rounded tops are slightly cut off by the red cedar border. It sits directly above the antennas and echoes their drooping arches. The center of the M has two white eyebrow-like lines further mimicking the antennas. The three shapes to the left, right, and bottom of the butterfly look like stylized flowers. They each have two floppy leaf-like shapes bending open to frame an oval flower bud. Any gaps between these shapes and the border are filled with copper triangles, protruding outward like little pyramids.

Just as a real butterfly’s wings are symmetrical, so are the wings of this abstract butterfly. However, there is much more at play in these abstracted wings than originally meets the eye. Each wing is actually made up of three hummingbirds. Their light green bodies are animated by the pale yellow background of the wings, and any major gaps between the birds are plugged in with various black and brown shapes. These filler shapes help maintain the flow of the overall design, but they also cause the shapes of the hummingbirds to blend in, making them difficult to pick out at first glance.

The hummingbirds have thin, teardrop-shaped bodies with long, narrow beaks coming out of their rounded heads. A thicker teardrop shape makes up the wing and connects over the middle of the body. Each bird has a little black dot for an eye and light brown accent marks on its wing and body. On each side of the butterfly, the three birds make up the top, middle, and bottom of the wing. The top birds soar upward at diagonals, poking the sharp end of their beaks into the top right and left butterfly wing corners. Their wings push behind them. The middle birds fly horizontally straight at one another so that the tips of their beaks meet where the butterfly’s wings connect. The wings of these middle birds point down. The bottom hummingbirds are in a slightly angled nose dive for the bottom of the whorl, their wings, perpendicular to their bodies, form the lower curve to the butterfly’s wings.

Bactrian Camel made by an Unknown artist in the 7th century

17 1/4″ X 9 1/4″ X 16″

Earthenware with white glaze

This realistic ceramic sculpture of a camel is almost a foot and a half tall, and, from nose to tail, it is just shy of a foot and half long. When made, it was fired with a white glaze. As we look at this sculpture today, nearly 1500 years after its creation, it is a light, creamy tan speckled here and there with dark yellow and light brown spots. Its color brings to mind the desert sands that camels are famous for traversing.

One glance can have viewers believing this is a one-humped camel. However, a closer look reveals a bulging pack slung over the camel’s back, nestled neatly and tightly between two humps. If not for the items stowed on and around it, the pack would deceivingly blend into the camel’s humps and sides.

Let’s take a moment to focus on the pack and its items. The pack itself has the look of a large, floppy duffle bag. Perhaps it contains rolled up clothes or fabric, since the ends of the pack, which rest against either side of the camel’s ribcage, appear smooth and rounded. A small, rectangular, carpet-like mat covers the top middle of the pack and rises slightly above the two obscured humps. Hanging from this mat on both sides are a number of objects ranging from lanterns and canteens to dead birds and rabbits. Even a gun perches precariously between the pack and the front hump. Helping to keep everything in place, two long, rectangular objects, one on each side of the camel, cross under the pack to run alongside the camel’s body just above the hip and shoulder joints. Bending slightly at the ends as if bowed by the pack’s weight, these rectangular objects appear to be stiff yet pliable in order to brace the camel’s humps and stabilize its load.

The camel seems unphased by the weight of its cargo, which isn’t surprising considering that a real-life camel can carry about 400 pounds on its back. The sculpture stands tall and strong with its weight evenly distributed amongst its four gangly legs. Its two-toed hooves are all planted firmly on a thin, rectangular, ceramic base. With its long neck arched up, the camel is at its full height.

Let’s look even closer at the camel’s physical details. Its eyes look straight ahead, and its chin has a proud upward tilt. Meanwhile, Its nostrils are slightly flared, and its mouth is partially open. The camel’s face and neck are accented by stylized hair shown as solid and smooth without any marks to indicate hair texture. The hair on top of the camel’s head runs in a rigid, blunt strip from the base of its neck, up past the ears, and rests between the camel’s eyes. A larger blunt strip of hair runs just underneath the chin to the bottom of the arched neck. At the very back of the camel, its little tail flicks to the left as if in anticipation for its long journey.