Use the interactive map to explore the museum

Search for art, find what you are looking for in the museum and much more.

Audio Description Tour: People

Sometimes images of people are used to express thoughts, or to record events, feelings or memories that may be difficult to show in other ways. Join us on an audio descriptive tour of some of the people captured in VMFA’s permanent collection.

Introduction

Sometimes images of people are used to express thoughts, or to record events, feelings or memories that may be difficult to show in other ways. Join us on an audio descriptive tour of some of the people captured in VMFA’s permanent collection.

Catfish Row

Catfish Row – Jacob Lawrence – 1947

Unframed: 17 3/8″ X 23 1/2 ” framed: (original artist-made pin-oak frame) 27 3/4 X 33 7/8

Egg tempera on hardboard

In 1947 the celebrated modernist Jacob Lawrence received a commission from Fortune magazine to depict African American life in the so-called Black Belt, a broad agricultural region of the Deep South. The artist spent a few weeks that summer traveling to Memphis, Vicksburg, and New Orleans, as well as various communities in Alabama. Catfish Row is one of ten temperas resulting from Lawrence’s journey. All painted on his return to New York. This dynamic painting, with its overall mood of abundance and pleasure, depicts the shared preparation and consumption of food in black communities that offered some respite from the hardships of racial discrimination in the postwar years.

At first glance, this painting is like walking into a small, crowded neighborhood bar and being hit with a wave of sounds and smells that pull you in multiple directions at once. Just under two and a half feet high and nearly 3 feet wide, this piece is packed with bold colors, abstracted people and objects, as well as diagonally-tilted horizontal and vertical lines. Initially, the scene may appear spontaneous and sporadic. However, in the same way that a well-run bar keeps things operating smoothly on its busiest night by maintaining an organized flow, Lawrence’s thoughtful use of colors, lines, and shapes creates an understated balance and structure that strategically directs the viewer’s eye so that nothing is missed.

Lawrence uses white lines to divide up space and create depth. One of these lines runs on a horizontal diagonal, splitting the scene into two unequal parts – roughly two thirds for the top section and one third for the bottom. The bottom third is further divided into four side-by-side sections, each with a black background. Inside each section is a different kind of seafood, which Lawrence visually breaks down into geometric and organic shapes to create a non-realistic impression of their real-life appearance. Moving from left to right, the first section contains long, blue, squid-like creatures with yellow eyes. The tops of their pointy heads are all directed diagonally towards the upper right corner of their confined box. The next section holds red crabs clambering over each other in different directions. Then comes a smattering of blue oysters, some of which are highlighted with a lighter blue to show their pearly, smooth inside. The last section on the right is filled with little red fish accented with yellow eyes and yellow fins. A lone yellow fish draws attention to Lawrence’s signature.

Let’s shift our focus to the top, two-third portion of the painting. It is divided into three areas of action by two very thick, vertical, white lines slightly angled towards each other to imply depth. These two lines also act as bar counters and each one is set with blue plates and red bottles. Between them is an open kitchen, so the customers on either side have an unobstructed view of the chefs and their work. The head chef, indicated by a white chef jacket and tall chef hat, stands in front of a horizontal stove top that runs along the bottom of the kitchen area. While most of the people in this painting are side-facing, he faces the viewer. He is joined by two sous chefs, wearing all white. One has their back turned and the other is handing a plate to an out-of-view customer at the top right. Looking closer at the right side, there are three customers at the bar leaning over their plates. The left side is a bit more crowded. Four customers, all in different phases of eating, lean against the bar while three customers behind them wait for an open spot. The outfits of the customers create a balanced mixture of red, green, yellow, and black.

Lawrence, himself a black artist, gives all the chefs and customers the same dark brown skin, emphasizing this establishment as a refuge for the black community. The portrayal of the people fits with the abstract style of the scene. Like the seafood being deconstructed into shapes, the people are shown in very minimal form. Lawrence’s use of abstraction takes his viewers on an immersive journey free of realism’s life-like distractions. The balanced, bright colors of the people’s clothing and accessories volleys the eye around the painting to create the sensory atmosphere of being in a crowded bar. The simplified forms amplify the emotional and physical possibilities in the people’s body language. We do not need to see all the realistic details to get the sense of satisfied joy as one customer on the left tilts his head all the way back to dangle a fresh oyster above his open mouth while reaching for the blue fish on his plate at the same time. We are drawn to the head chef’s eyes, because they are the only facial feature that Lawrence gives him, which intensifies his concentration on a frying pan of sizzling blue shapes. By breaking down the realistic into basic elements of art, Lawrence creates an atmospheric scene that is all at once busy yet succinct and chaotic yet balanced.

Septimius Severus

Septimius Severus – Artist unknown – ca 200 AD with 17th century additions and modification

86″ X 47″ X 37″

Marble

Label Copy

This statue of Septimius Severus (reigned 193 – 211), a Roman emperor born in Africa,

exemplifies the baroque restoration practices of the 1630s, when patrons and restorers valued the beauty of a complete work of art rather than (as today) an appreciation for the fragment. The head and body belong to two different ancient statues and were probably joined in the 1630s, when restorers added newly made arms, legs, and other elements. The statue once belonged to the renowned Roman collector Vincenzo Giustiani (1564 – 1637), who had a museum of ancient sculpture and was also an early patron of the artist Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio.

Just over seven feet tall and standing on an over three foot pedestal, this statue of Septimius Severus takes an imposing position. This statue was once quite colorful, but those colors have long since faded. Now the entire sculpture is the same whitish grey as the marble from which it is composed.

The statue seems to show Septimius in his mid-40s. At the back of his head, his hair curls in little tendrils that cling just below the base of his skull. In front, while most of his curls gracefully frame his face as if swept back by a gentle breeze, a small, rebellious tangle of curls falls forward to rest just above the middle of his forehead. He has a full, curly beard with a slight part in the middle. His thick mustache covers his upper lip but not enough to completely hide what could be a very faint smile.

Let’s widen our focus to take in the rest of Septimius. He is slim but muscular and wearing a tunic that falls just above his kneecaps. The tunic blouses at the waist to suggest he is wearing a belt. His sandals have thick straps that circle his legs all the way up to mid-calf. The final touch is a floor length cloak. From its circular clasp at the top of his right shoulder, the cloak drapes elegantly across his collar bone and falls over his left shoulder, covering most of his left arm.

To get a feel for his authoritative stance, let’s place ourselves in the same position as Septimius either physically or just with our imaginations. Start from a neutral position with your feet hips’ distance apart, arms loose at your sides, and your head facing forward. Now move your left foot so that it is slightly ahead of your right. Shift your weight back into your right leg and allow the left knee to bend slightly. Add a very slight bend to your left elbow, and imagine you are clutching the folds of his long cloak in your left hand. Raise your right hand straight out from your side as if you are trying to balance your weight. Bend your elbow to bring your right hand forward as though you are raising a glass to make a toast, except in the case of Septimius, you are holding a scroll. Now, turn your head ever so slightly to the right to look towards your raised right hand. Hold this pose for a second to get a sense of how it feels in your body.

Willem van Heythuysen

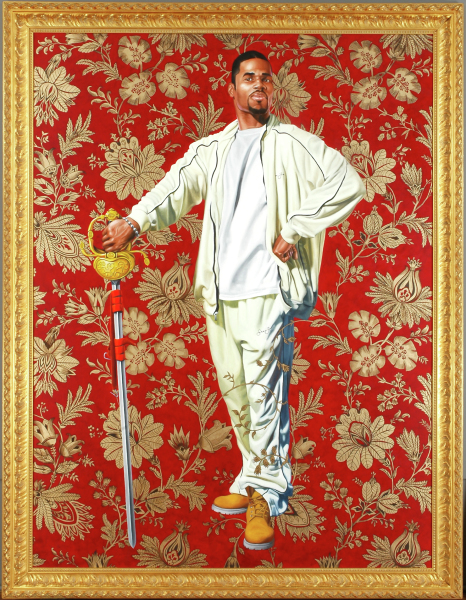

Willem van Heythuysen – Kehinde Wiley – 2006

Oil and enamel on canvas

Label Copy

A big part of what I’m questioning in my work is what does it mean to be authentic, to be real, to be a genuine article or an absolute fake? What does it mean to be a real black man? Realness is a term applied so heavily to black men in our society. – Kehinde Wiley

Wiley’s lavish larger-than-life images of African American men play on Old master paintings. His realistic portraits offer the spectacle and beauty of traditional European art while simultaneously critiquing their exclusion of people of color.

This portrait of Willem van Heythuysen references a 1625 painting of a Dutch merchant by

Frans Hals., whose bravura portraits helped define Holland’s Golden Age. Wiley’s model, from

Harlem, New York, here takes the name of the original sitter from Haarlem, the Netherlands,

whose pose and attitude he mimics. Despite the wide gold frame and the vibrantly patterned

background with Indian-inspired tendrils encircling his legs, this subject’s stylish Sean John street wear and Timberland boots keep him firmly in the present and in urban America.

Moved from its original location in the museum’s 21st Century Gallery, this work foregrounds the rich dialogues that exist between geographies, time and cultures.

In its frame, this realistic portrait stands almost nine feet high, almost seven feet wide, and from its position on the wall, even a very tall person has to tilt their head back to look up at the black man poised in the center of the canvas. Kehinde Wiley has talked about the scale and grandeur of EuroOld Master paintings – the larger-than-life European portraits from which he draws his inspiration – and he has mentioned that their size and the height at which they hang on the wall suggests that if you, as the viewer, were physically in the room with the subjects of these paintings, this would be your view, because you would be on your knees in front of them. The predominately white subjects of these Old Master portraits paid large sums of money for their painted likenesses to exude this strong sense of power and status. This painting of Wiley’s, along with its ornate, gold frame, captures that feeling with the man’s confident presence, appraising gaze, and 2006 brand name clothing in a way that both nods at and critiques the Old Master tradition.

The Willem of Wiley’s portrait has golden, brown skin and a line up hairstyle that is close-cropped and marked by clean lines that clearly define his forehead, temples, and sideburns. His slim mustache runs thinly and evenly into a trim goatee, lightly connected to a small patch of hair under his bottom lip. His lips are impassive without a smile or a frown. The tiny upward tilt of his squarish jaw gives an impression of stoic authority. There is a softness in his eyes, one faint crease line on his forehead, and a slight furrow between his brows. Though he seems to be directing his gaze at something specific, there is an aspect of introspection in his expression.

He is wearing a creamy white Sean Jean tracksuit that has very thin black accent lines along the jacket’s front zipper, down the arms on either side of his elbows, and down the outside of the pent legs. The subtle Sean Jean logo – Sean Jean’s signature – appears in black writing over the jacket’s upper left chest as well as on the upper left thigh of the pants. The jacket is completely unzipped to reveal a plain white t-shirt underneath. The Jacket hangs just below the hem of the t-shirt. He is wearing Timberland boots – ankle high, work boots made with a yellowish tan suede and a thick whitish grey sole. It is hard to tell if the boots are untied or just loosely laced, because the hem of his pants lands in long folds that spill over the sides of his boots.

Now, let’s get a sense of his stance. Try it on your own body if you’d like or just imagine to see how it feels. Let’s start from a neutral position with your feet hips’ distance apart, arms loose at your sides, and your head facing forward. Take a small step forward with your left foot, and turn your right foot out to a 45 degree angle. Let your hips follow your right foot, but do your best to keep your chest facing forward. Keeping your neck nice and tall, turn your head slightly toward your left shoulder, and raise your chin just a touch. Look slightly down and to the right. Make a fist with your left hand and rest it squarely on your front, left hip bone. Raise your right arm out straight, in line with the angle of your right foot, and at a height just above your right hip. With this hand, you are gripping the handle of a sword with the backside of your hand facing forward. The sword has a large, fancy, gold hilt with a squiggly, tadpole design on it, and its point comes all the way down to rest about a foot and a half out from your left foot. A bright red strip of fabric is tied around the blade up near the hilt in a manner that appears decorative and ceremonial.

The sword might look out of place next to the Sean Jean tracksuit if it weren’t for the painting’s background. With a deep, vibrant red almost obscured by large, stylized, gold flowers and gold, vine-like leaves, It looks like it would be velvet to the touch. Although the man has a three dimensional quality, the background, in contrast, appears two dimensional except for a few of the golden vines that creep forward in an attempt to encircle the man’s left leg. The background seems to suspend him in a richness and spendor that has no clearly distinct time period or specific location.