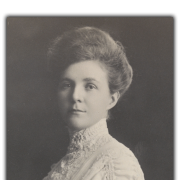

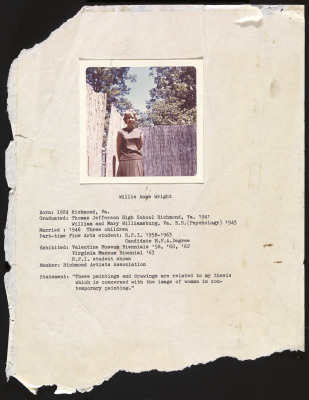

For more than sixty years, artist Willie Anne Wright has created alluring, witty, and provocative pictures that merge past with present, coaxing hidden narratives from the surfaces of reality. Born in Richmond in 1924, Wright studied psychology and art at William & Mary. In 1946, she married John “Jack” Wright, with whom she raised three children, all while taking art classes at night. In 1960, she entered the MFA program at Richmond Professional Institute (now Virginia Commonwealth University), where she met and was mentored by its founder, Theresa Pollak.

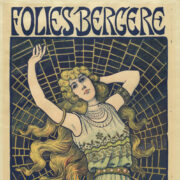

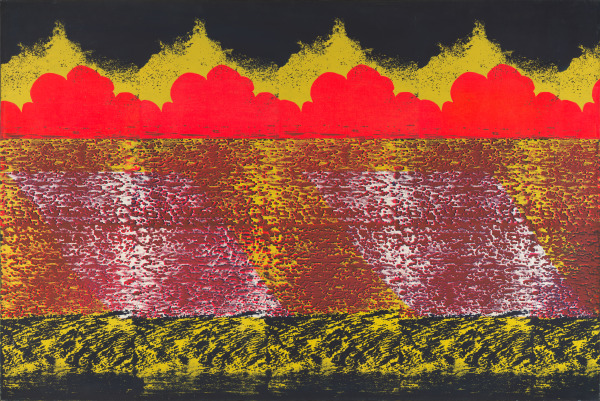

Wright quickly forged a distinctive style that merged a contemporary Pop Art sensibility with canny references to a longer history of art. Her paintings reveal a fascination with changing roles of women and new forms of media, like television. She exhibited work all over Virginia, notably in a 1967 solo show at VMFA’s Robinson House, and as part of a major survey of American painting at VMFA in 1970.

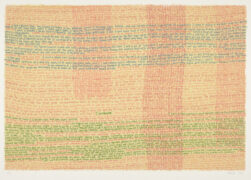

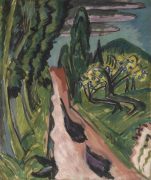

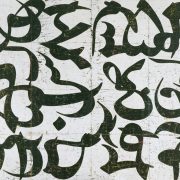

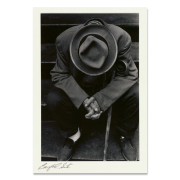

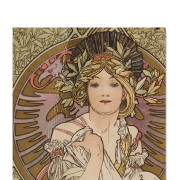

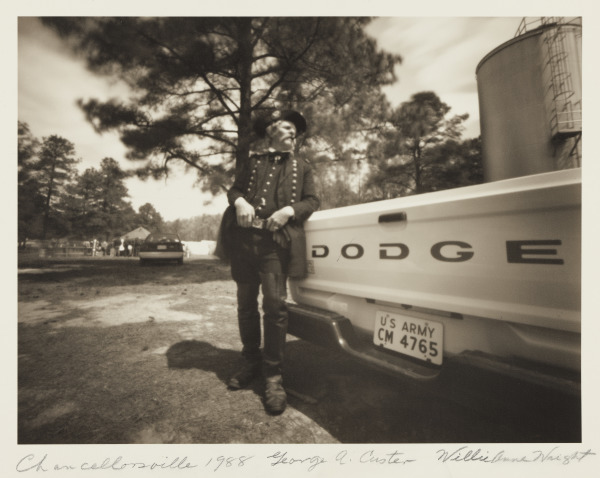

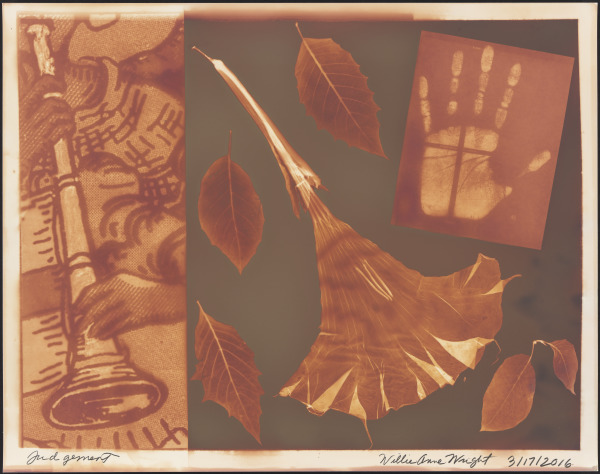

In 1972, Wright took a photography class and learned how to make a pinhole camera. This simple box with a tiny hole and sheet of photographic paper or film changed her life as an artist. Over the next four decades, Wright produced a revelatory body of photographs, from imaginative self-portraits and witty still lifes to studies of Civil War reenactors, somber landscapes, and complex photograms invoking Victorian culture. This Collection Story was created in conjunction with the special exhibition Willie Anne Wright: Artist and Alchemist (on view at VMFA from October 21 – April 28, 2024). This is the first museum exhibition to celebrate the full sweep of this artist’s remarkable career.

To learn more about the exhibition please visit the exhibition page.