Ted Joans

Search for art, find what you are looking for in the museum and much more.

The Impressionists, and later the Postimpressionists, were both lauded and criticized for their revolutionary painting techniques, yet these artists were equally groundbreaking in their radical drawing practices. This story presents the innovative role drawing played in the artistic process of the Impressionists.

On April 15, 1874, the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Printmakers, etc. opened an exhibition of their work in Paris, at the studio of the photographer Nadar. Although not mentioned in the lengthy title, drawing also featured prominently, as well as in the seven subsequent shows the group organized. Critics responded to the show passionately, commenting on the innovative approaches to conveying contemporary life adopted by the participating artists, including Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. One particularly harsh review described Monet as an “Impressionist” and the group eventually adopted the name as their own.

150 years later, Impressionism is often remembered for its colorful painting, and the radical works that shocked nineteenth-century viewers now seem at home in today’s museum galleries. However, an avant-garde drawing practice was fundamental to the Impressionists, and later to the Postimpressionists as well, allowing artists to explore modern compositions, subjects, and techniques. Impressionist draughtsmen synthesized the solid, neoclassical approach to line embodied by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and adapted it to capture the ephemeral conditions of their surroundings. On paper, with watercolor, pastel, chalk, and graphite, they had the freedom to be their most experimental.

Cham (Amédée de Noé), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Cham (Amédée de Noé), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons “An exhibition of so called ‘paintings’ has opened… One finds, displayed to his affrighted eyes a horrifying spectacle. Five or six lunatics, one of whom is a woman, a group of unfortunates afflicted with the madness of ambition, have got together there to exhibit their works.”

–Albert Wolf, Le Figaro, 1876

This Collection Story was created in conjunction with the installation Experimental Lines: Impressionist and Postimpressionist Drawings from the Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon (on view at VMFA from March 23 – January 1, 2025). To learn more about the exhibition please visit the exhibition page.

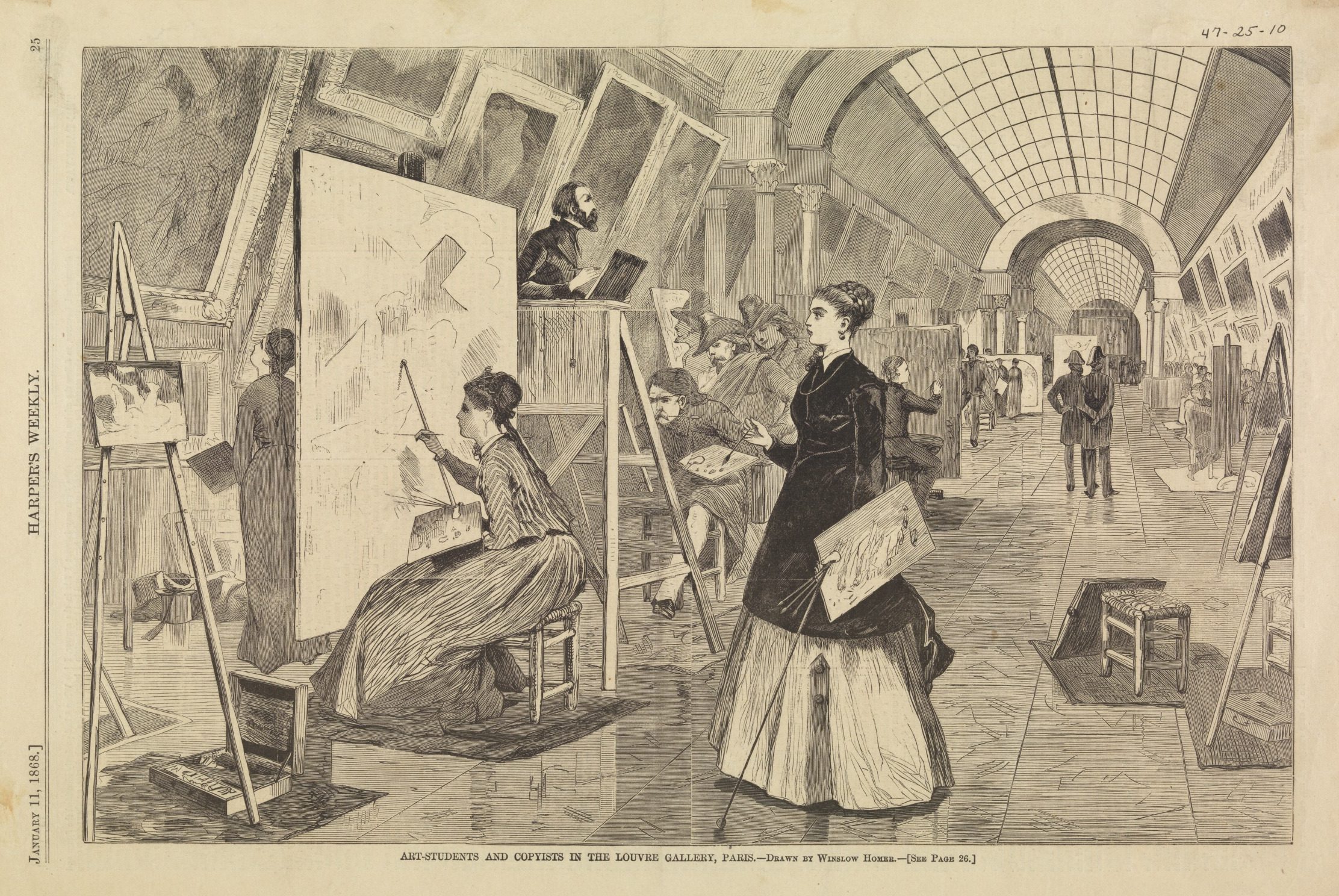

In the early nineteenth century, drawing was considered the foundation of an artistic education. Students at the École des Beaux-Arts honed their drawing skills working from plaster casts, live models, and by copying works at the Louvre as seen in this image from an 1868 edition of Harper’s Weekly. Academicians believed a rigorous education in draftsmanship was essential for strong paintings and sculptures – a perspective that was espoused by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and other neoclassical artists.

Art Students and Copyists in the Louvre Gallery, Paris, from Harper's Weekly, January 11, 1868, 47.25.10

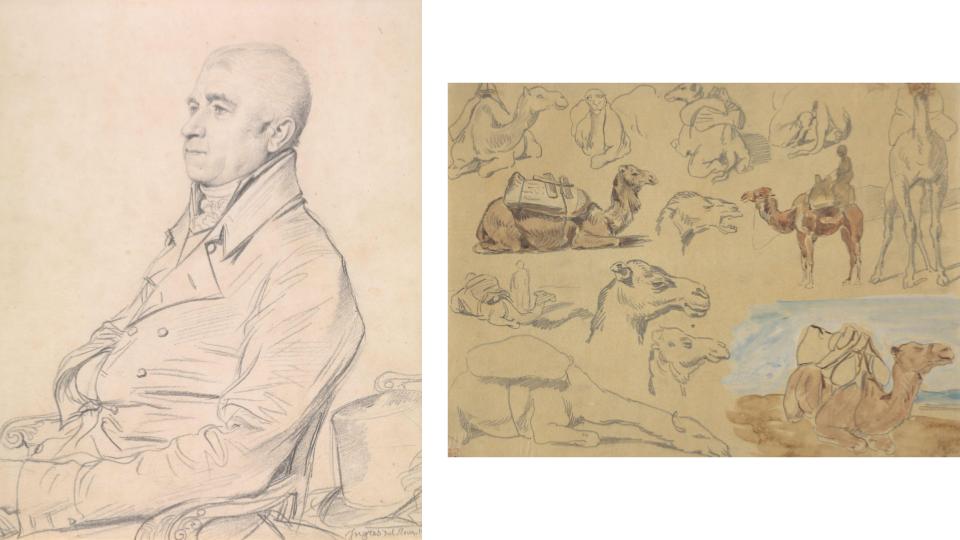

By the 1820s, Ingres was often contrasted with Eugène Delacroix, an artist associated with Romanticism, an artistic movement that emphasized color over line. Artists have debated the importance of line versus color since the Renaissance. Ingres’s commitment to the principles of the French Academy helped him to earn its most prestigious award, the Prix de Rome, which funded travel in Italy. During this time, Ingres studied ancient sculpture and Renaissance and Baroque painting, refining his neoclassical style. After he exhausted his prize winnings, he used his drawing skills to fund his stay in Rome, creating graphite portraits of French and British tourists, like this depiction of Reverand Church below.

On the other hand, even as a young artist, Delacroix focused primarily on color over line. Yet he was also a prolific draughtsman, and his drawings show that the two concepts were not mutually exclusive. In 1832 he participated in a French diplomatic envoy to Morocco, where he drew from life, filling several sketchbooks. Delacroix looked back on these drawings after he returned to France and North African themes informed his work for the rest of his career. In the example below, he depicts a camel from multiple vantage points and with varying media and levels of finish, offering the artist a range of compositions on which to draw on for subsequent compositions.

In the mid nineteenth-century, artists of the Barbizon school renewed attention on the genre of landscape and brought drawing out of the studio and into the environment, helping to pave the way for the plein air works the Impressionists were best known for. These earlier nineteenth-century precedents served as inspiration for the Impressionist and Postimpressionist artists of subsequent generations.

(left) The Reverend Joseph Church, Rector of Frettenham, 1816, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (French, 1780-1867), pencil on paper. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Collection of Mr. And Mrs. Paul Mellon, 95.35; (right) Studies of Camels, 1832, Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863), watercolor and graphite on wove paper. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 2006.52

The portability of drawing materials like paper, pencil, and watercolor made them well suited for artists working away from the studio.

The precision achieved through drawing made it a useful medium for documenting the natural world. Botanical illustrations were often created with watercolor, which was able to convey the range of colors observed in plants. Here Delacroix presents drawings of a narcissus, or daffodil, and a primrose, as scientific specimens, isolating the form of the flowers on otherwise blank sheets of paper. However, upon closer inspection, his loose handling of watercolor is evident, reaching beyond the pencil outlines in some petals and leaving areas of bare paper in others. In this way, Delacroix subverts the conventions on botanical illustration to provide a more Romantic experience of nature.

(left) Narcissus, ca. 1832–48, Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863), watercolor on wove paper. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 95.26; (right) Primulas, early 19th century, Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863), watercolor with graphite on wove paper. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 95.31

“Everything that is painted directly and on the spot always has strength, a power, and a vivacity of touch one cannot recover in the studio. Three strokes of the brush in front of nature are worth more than two days of work at the easel in the studio.”

— Eugene Boudin

The expansion of the rail network during the nineteenth century greatly enhanced the opportunities for travel throughout France. Artist Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot regularly traveled from Paris to the villages near the forest of Fontainebleau, where he was an active member of the group of landscape painters known as the Barbizon school. At first, Corot sketched on site in the forest and then returned to his studio in Paris to compose paintings based on his drawing, but by the end of his career he was also working entirely outdoors, or en plein air, and his depictions of the landscape were becoming looser, as can be seen in the rapid lines of this drawing.

These earlier nineteenth-century precedents paved the way for the Impressionist and Postimpressionist artists of subsequent generations to work outdoors, seek inspiration from nature and continue to explore the relationship between line and color in their work. Read on to explore the Impressionist approach by examining the chosen subject matter of artists like Berthe Morisot, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro.

Historical and mythological paintings were privileged by the Academy, the official government institution that oversaw the training and exhibition of artists in France. Rather than focusing these genres, the Impressionists turned to their own surroundings for subject matter, depicting landscapes and everyday life in the changing environs of Paris and its suburbs. A recurring motif was the leisure activities of the emerging bourgeoisie, including visits to the racetrack and circus or vacations to seaside villages in Northern France. Through exploring these subjects, Impressionism chronicled the class divisions and growing divide between urban and rural communities in the late nineteenth century. Drawing was essential to this – paper, sketchbooks, and drawing materials were readily available and could be easily transported and were thus ideal for sketching chance encounters and fleeting environmental conditions.

The nineteenth century was a period of rapid industrialization and urban development. Impressionist art grabbled with this changing environment indirectly – factories can often be seen in the background of landscapes. For Morisot, watercolor was an ideal medium to articulate plumes of dark smoke emerging from the chimneys in the distance on the left. With just a few strokes of bright blue, she evokes the patches of sky that break through clouds on an overcast day, providing a stark contrast to the muted tones of the boats and harbor. It was unusual for women artists to depict industrial landscapes, however, Morisot, who often vacationed with her family to coastal locations in France and England, captured harbor scenes and shipyards throughout the 1870s and 1880s, often in watercolor.

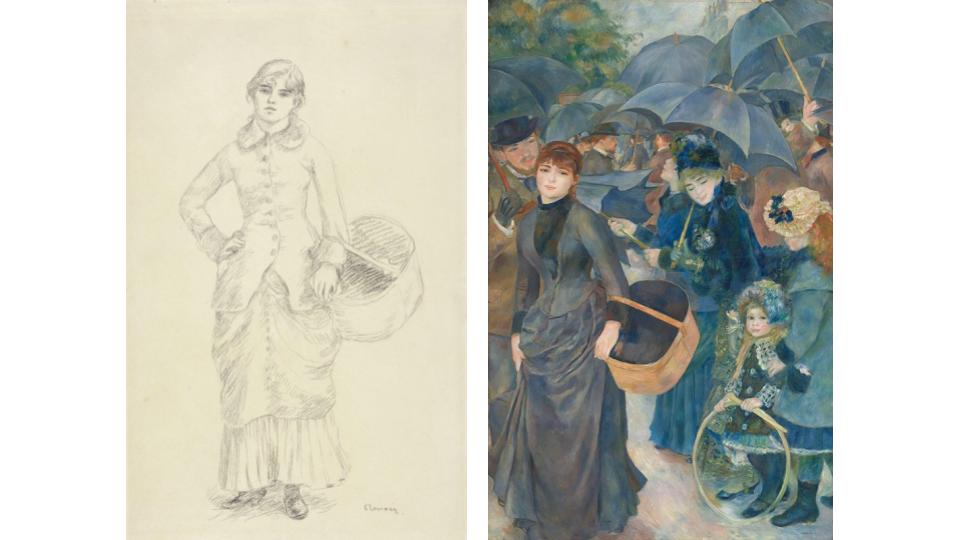

Renoir created this sketch, which may depict the artist Suzanne Valadon, his frequent model, when he was developing his major painting, The Umbrellas. Ultimately, he chose to depict the figure of the milliner in a different pose, but drawing provided him with the opportunity to test out different compositional possibilities. This work was created at a moment when Renoir was increasingly interested in drawing as the root of the rest of this artistic practice, as his work took a more linear, classicizing direction. He remarked to his friend, the dealer Ambroise Vollard, that,

“I had come to the end of Impressionism and was reaching the conclusion that I didn’t know how either to paint or draw.”

Returning to drawing as the basis for all other media was essential to Renoir during this transitional moment, enabling him to develop new ideas and refine techniques.

(left) The Milliner, ca. 1879, Pierre-Auguste Renoir (French, 1841–1919), black chalk on wove paper. Virginia Musuem of Fine Arts, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 95.42; (right) Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Umbrellas, about 1881-6, oil on canvas, 180.3 × 114.9 cm, Sir Hugh Lane Bequest, 1917, The National Gallery, London. In partnership with Hugh Lane Gallery,Dublin. NG3268, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/NG3268

Degas was among the most prolific draughtsmen of the Impressionist group. As a young artist he studied the work of Ingres and absorbed his linear approach. Though he worked in a range of drawing material throughout his career, he was initially drawn to pastel because the matte qualities of the medium recalled the frescoes he had admired during a formative trip to Italy.

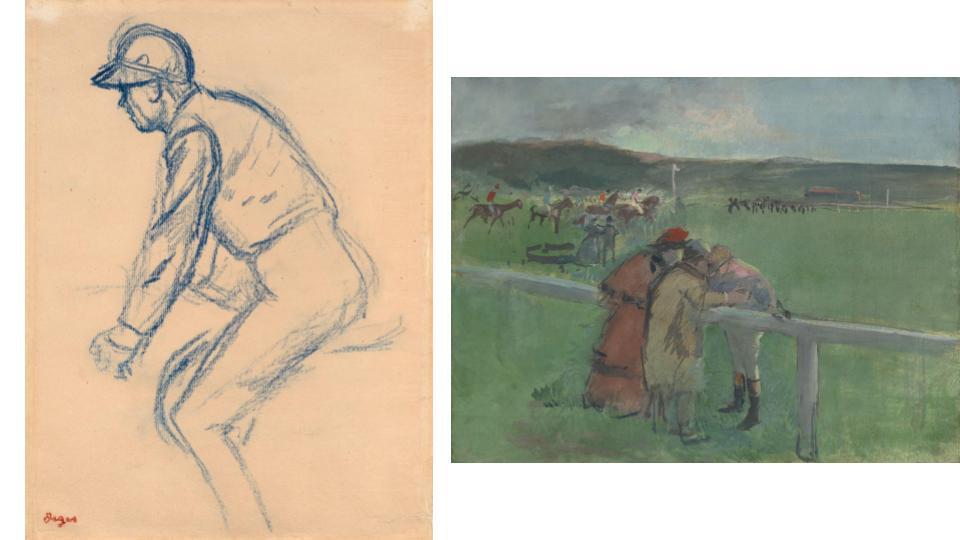

Degas was a frequent visitor to the racetracks at Longchamp in Paris, repeatedly depicting both riders and spectators. His immersion into the space gave him ample opportunities to study horses and jockeys both in motion and at rest. The Impressionists, especially Degas and Monet, became known for their seriality – returning to the same motif again and again. Throughout his career, Degas created works related to horses and racing in painting, sculpture, prints, and drawings. Drawing enabled him to work on site at the track, in the stands where it would not have been feasible to set up an easel.

In 1879, Degas invited several younger artists, including Jean-Louis Forain to participate in the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition. Forain looked to Degas as a mentor and shared his interest in the racetrack, although his work often considered the interaction between figures in the crowd and he had a looser approach to line, as seen in this gouache, a kind of opaque watercolor that combines the rich colors of oil paint with the spontaneity of watercolor.

Like Degas and Forain, Paul Mellon maintained a passionate interest in horse racing. Equestrian subjects abound in the Mellon Collection, helping to shed light on a pastime that was especially popular in nineteenth-century France. This pastel drawing by Degas was a gift from Rachel “Bunny” Mellon to her husband and was among the first works of art that the couple collected together.

(left) Jockey Facing Left, ca. 1870-80, Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917), blue pastel on laid paper. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Collection of Mr. And Mrs. Paul Mellon, 99.105; (right) The Good Tip, ca. 1891,Jean-Louis Forain (French, 1852–1931), gouache on paperboard mounted on a cradled panel. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 85.769

The Impressionist painters, though united in many aspects, maintained their individuality as artists throughout their careers. Their influence guided a generation of painters who followed the paths established by the Impressionists and then forged new direction of their own.

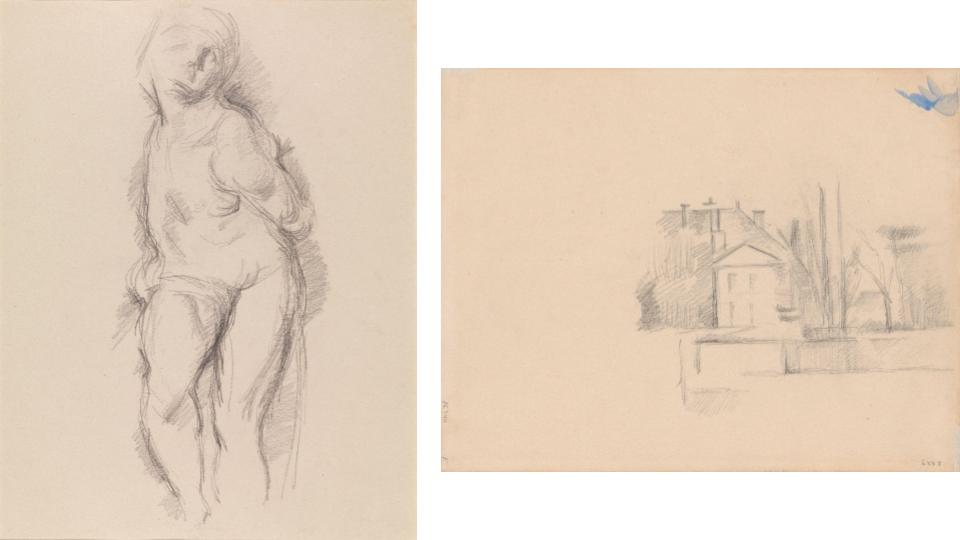

Cézanne kept several sketchbooks simultaneously and moving back and forth between them. This sheet is from a sketchbook he used from the early 1880s through 1900, although it has since been taken apart and its sheets are now housed in collections across the globe.

Cézanne carried his sketchbooks with him – on the verso is a drawing he made at the Louvre, after a sculpture by Michaelangelo – and he would have made this rendering of a house in the woods from life. Through his careful use of line and shading, Cézanne conveys a sense of compressed space as the negative space of the house seems to emerge from the dense trees. Repeated vertical lines suggest chimneys and tree trunks without delineating those forms completely and a few brushstrokes of blue watercolor at the top right corner suggest the sky. Cezanne also adopted this purposeful use of negative space in his paintings where he left areas of bare canvas. A generation later, Cezanne’s delineated forms and use of negative space would inspire Cubist artists.

Recto: Study of a Slave, after Michelangelo; Verso: House and Trees, 1881-84, Paul Cezanne (French, 1839-1906), graphite on wove paper. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 85.744

Seurat produced more than five hundred drawings during his brief career. Friends recalled him drawing by candlelight and his works on paper convey a contrast between deep shadows and bright white that evokes the ambiance of evening. Seurat achieved this effect with his use of very specific materials, to which he remained loyal throughout his life – black conté crayon and a particular type of laid paper, manufactured by Michellet. Seurat applied the crayon in a manner that emphasized the texture of the sheet, with small areas of bare paper remaining visible in the midst of areas of velvety black. The disjunction between black and white evident throughout his drawings evokes the relationship between carefully placed dots of differently colored paint in the pointillist works he is best known for, like Houses and Garden from ca. 1882. Throughout his oeuvre, Seurat explored the effects of strategically applied media in opposing colors.

(left) The White Horse, ca. 1882, Georges Seurat (French, 1859–1891), black crayon on laid paper. Virginia Musuem of Fine Arts, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 85.809; (right) Houses and Garden, ca. 1882, Georges Seurat (French, 1859–1891), oil on canvas. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 2014.210

Like their Neoclassical and Romantic predecessors, the Impressionists and Postimpressionists turned to drawing regularly as a way to record the world around them, refine their ideas, and experiment with new techniques. Today, these fragile works on paper are on view for short periods of time only. You can see these drawings, and others, on view in Experimental Lines through January 1, 2025, but VMFA is also home to a stunning collection of Impressionist paintings and sculpture, and these works are always on view in the Mellon Galleries.

Explore more of the Mellon Collection