Theatrics of Social Life in the Age of Enlightenment

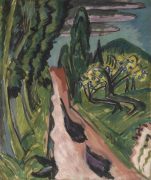

(Left) A Serenade Near a Fountain, ca. 1725, Jaques de Lajoue (French, 1687-1761), oil on canvas. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, The Jordan and Thomas A. Saunders III Collection, L2020.6.68. (Right) The Gazer (Le Lorgneur), ca. 1716, Jean-Antoine Watteau (French, 1684-1721), oil on panel. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 55.22.

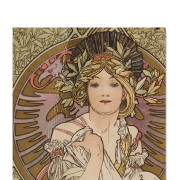

Colorful, lush, and bursting with fantasy and wit, the art of Jacques de Lajoue perfectly embodies what came to be known as the Rococo picturesque genre in early 18th-century France. The artist was a decorator as well as a painter, and inventive depictions of dreamlike park and garden scenes like this one were immensely fashionable as decorative panels. Lajoue’s paintings and decors were intended to surround his aristocratic patrons with the creations of his fantastic imagination. He often incorporated surprising interactions between the painting’s human characters and the inanimate figures that decorated sculpture or architecture in the composition. This work features two actors of the commedia dell’arte (a popular form of improvised theater using stock characters and situations) serenading a lone woman, each man apparently hoping to seduce her with his talent. This trivial scene of everyday desires occupies only a small portion of the canvas. Clearly, Lajoue preferred to devote considerable space to the lavishly ornate and monumentally sized fountain. Although the woman’s reaction is not visible to the viewer, the sculpted nymphs that laze upon the fountain appear completely enamored with the performance.

Jean-Antoine Watteau’s colorful palette, sketch-like brushwork, and wistful tableaus were so different from the academic paintings usually accepted by the French Academy that it created a new term, fete galante, to describe his works. This new genre offered tantalizing, dreamlike glimpses into the amorous amusements of elegantly attired French aristocrats, usually set within a garden or park.

In this idyllic scene, a young man in a striped, shimmering costume strums a guitar as he gazes at a young woman toying with a fan. Behind them, the flute player leans toward the woman but keeps his eyes on his fellow player. Watteau frequently included stock characters from popular theater productions in his scenes, which sometimes leaves viewers wondering whether these figures are actors playing aristocrats or aristocrats emulating actors. The woman and two male performers in Serenade near a Fountain, a painting by Jacques de Lajoue also on this wall, were probably inspired by the trio of figures in this work.