Ted Joans

Search for art, find what you are looking for in the museum and much more.

Explore connections between works of art from across time and place. By placing works in unexpected pairings, we can discover new perspectives, overlooked context, and a better understanding of an artwork’s impact on the world.

Where an artwork is displayed in a museum can highlight important context as well as illuminate nuanced perspectives on history, race, socioeconomics, and more. Encyclopedic art museums, like VMFA, offer the visitor a unique opportunity to view artwork from all over the world, sometimes displayed side-by-side with works from a different time and place. This collection story presents works from the American, Native American, Modern and Contemporary, African, European, and South Asian galleries paired in “conversation” in unexpected ways. These pairings allow viewers the chance to uncover cross-cultural connections and viewpoints.

Imagine the conversations between the artists who created these works or even between the works themselves!

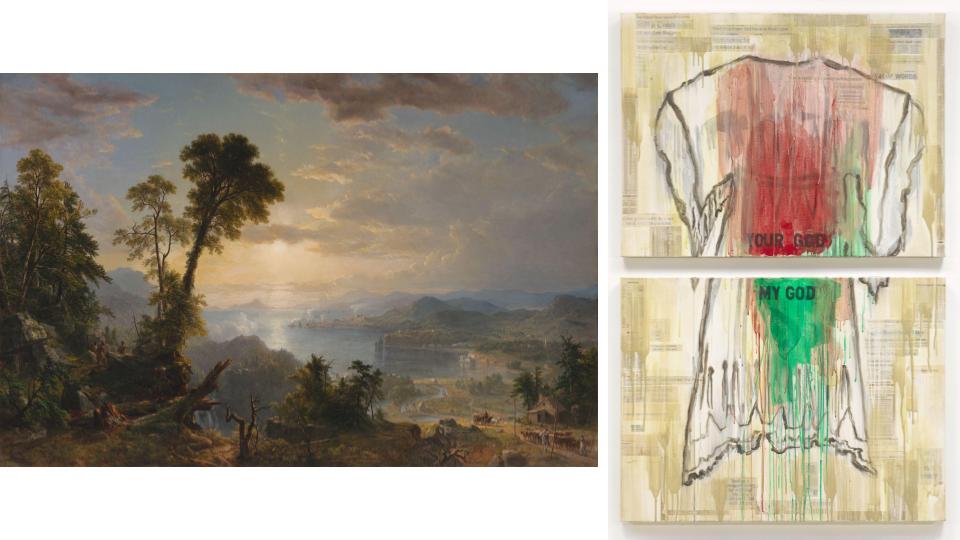

(Left) Progress: The Advance of Civilization, 1853, Asher B. Durand (American, 1796-1886), oil on canvas. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Gift of an Anonymous Donor, 2018.547. (Right) War Torn Dress, 2002, Jaune Quick-To-See Smith (American, Salish/Kootinai, born 1940), mixed media on canvas. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment, 2018.353a-b

One of the most identifiable paintings by Asher B. Durand, a member of the later-attributed Hudson River school of landscape painters, Progress: The Advance of Civilization, points to several aspects of cultural and social history, including ecology, Native American policies, railroads and the Industrial Revolution. Offsetting the locomotive, canal, townscape, and the log cabin at right, the Native American presence (relegated to the left foreground) reminds us of the sacrifices engendered by the “advance of civilization.”

Native American visual artist and curator Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith’s War-Torn Dress presents a legacy that is more cautionary than celebratory. The implication of a body inspires contemplation on Native lives lost and the contested spaces they occupied. Here, the Native presence is front and center, rather than relegated to a small detail. Placed prominently across the dress, “Your God, My God” proposes that within the fight over whose God is greater, all people reside in the Sacred, breathe the same air, and are of the same life force.

(Left) Chief’s Stool (Tabouret Ngombe), late 19th century, Ngombe Peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo, lacquered wood, brass and iron tacks. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, gift of Mrs. Alfred duPont, by exchange, 2022.25. (Right) Tabouret (for Jacques Doucet’s apartment, Avenue du Bois, Paris, then, later, his studio, hotel de la rue Saint-James, Neuilly, France), ca. 1923, Pierre Legrain (French, 1889 – 1929), lacquer, wood, gilding, horn. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Sydney and Frances Lewis Endowment Fund, 92.5

The form of this tabouret was inspired by stools made by Ngombe craftsmen. The Ngombe people live in central Africa in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (known as the Belgian Congo in the 1920s). Typically carved from one block of wood, a stool like this would serve a functional purpose, while at the same time, symbolizing the high level of prestige and rank of the owner In many African societies, stools and chairs are considered significant objects of leadership regalia. They are often richly ornamented with precious materials to underscore a ruler’s power, wealth, and status. The creator of this stool paid special attention to the surface design, using brass tacks to embellish the seat with zigzag patterns. The seat and back fuse together to form a subtle curve onto which the sitter could have reclined.

Chairs like this one became very popular among European elites during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Art Deco was a new visual arts trend that first appeared in France shortly after WWI (1914 – 1918), featuring straight lines, symmetry and repeating geometric shapes and was influenced by ideas and imagery borrowed from Africa and Asia. During an era of French Colonial trade, various Parisian museums and dealers collected objects from Africa, which helped to perpetuate a fascination with “exoticism.” French designers and artists were encouraged to explore new materials, techniques, and forms that evoked faraway places.

French bookbinder and designer, Pierre Legrain (1889 – 1929) became well-known for taking African art forms and adapting them into French Art Deco design. Commissioned by French couturier, Jacques Doucet (1853 – 1929), the stool (as well as other African-inspired furniture) was designed specifically for his apartment, to complement his collection of African sculpture and modern European art. While the overall form of Legrain’s stool resembles the Ngombe version, his materials and ornamentation conform more to the French style of lacquered surfaces and geometric designs. The tabouret is painted in a translucent, deep red lacquer, revealing the rich brown color of the wood beneath. Along the surface of the backrest a pattern of triangles forming a pyramid are carved in relief and gilded. The legs are symmetrically beveled creating a streamlined aesthetic, typical of Art Deco design.

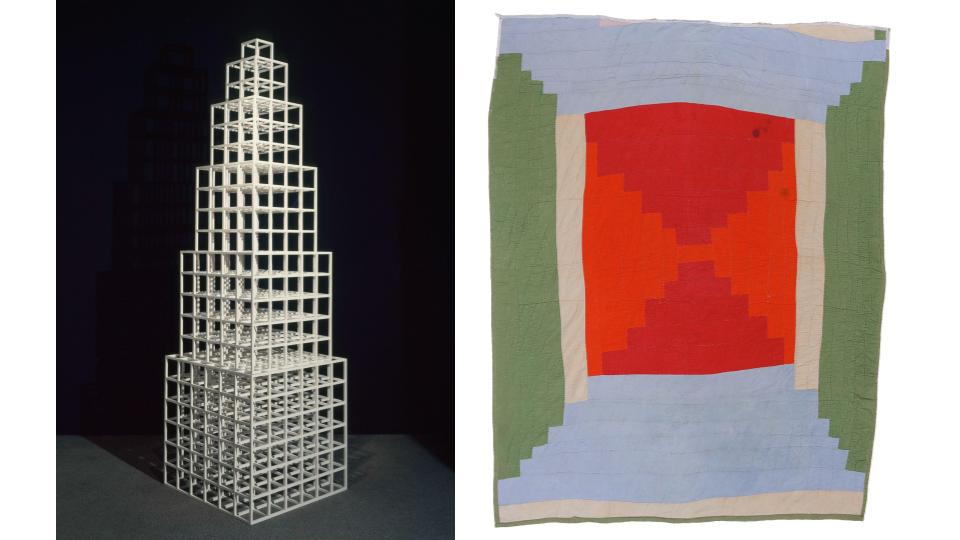

(Left) 1 2 3 4 5 6, 1978, Sol LeWitt (American, 1928 – 2007), painted wood. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, gift of the Sydney and Frances Lewis Foundation, 85.555. (Right) “Housetop” single-block “Courthouse Steps” variation, ca 1945, Jennie Pettway (American, 1900 – 1990), corduroy. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund and partial gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2018.68

Sol LeWitt, a founder of Conceptual Art, rejected Abstract Expressionism’s glorification of the artist’s own thoughts and emotions and emphasized instead a rational, objective approach to form. The meaning of LeWitt’s work—in sculpture, works on paper, and wall drawings—lies in its concepts and planning; its physical form is merely a way to communicate these concepts in visual terms.

Lewitt’s sculpture 1 2 3 4 5 6 continues a series of open modular cubic structures LeWitt began in the mid-1960s. This imposing tower comes from a simple routine for multiplication—1X1, 2X2, 3X3, etc.—that results in adding one more row to each descending level of stacked cubes. The top tier is a single unit, while the bottom tier is cubed 6X6X6 units. This basic formula yields surprisingly complex visual results as the viewer peers into the work from various angles.

Jennie Pettway’s, a quiltmaker from Gee’s Bend (now Boykin, Alabama), approach to quilt making refutes any known pattern but instead relies upon the artist’s sense of improvisation and aesthetic. Despite this, Pettway’s bold use of color and geometric form offers a great visual exchange with 1 2 3 4 5 6. Since the acquisition of 13 quilts by Gee’s Bend artists in 2019, a new quilt has been featured in the Minimalism Galleries every eight months. This continual rotation is necessary given the fragility of the medium and offers new dialogue and insight with each quilt that is displayed in the space.

(Left) Full-length portrait of William Henry Lambton (1764-1797) in a Van Dyck style costume, 1797, Angelica Kauffman (Swiss, 1741-1807), oil on canvas. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, gift of Mrs. A.D. Williams, by exchange, Gift of the Josephine Bay Paul and Michael Paul Foundation, Inc. and the Charles Ilrick and Joseph Bay Paul Foundation, Inc., by exchange, and Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, by exchange, 2022.76. (Right) Willem van Heythuysen, 2006, Kehinde Wiley, (American, b. 1977), oil on canvas. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Fund, 2006.14

Full-length portrait of William Henry Lambton (1764-1797) in a Van Dyck style costume presents the quintessential characteristics of the Grand Tour portrait tradition. The sitter, a wealthy member of the British Parliament traveling through Italy at the time, is dressed in a fancy and anachronistic 17th-century costume. He stands on a terrace that opens onto a mountainous landscape. Next to him, a depiction of the Medici vase, one of the most celebrated pieces still extant from the Greek classical period (AD 1st century), shows his cultural interest as an educated traveler and art connoisseur. The artist, Angelica Kauffman, represents Lambton in an attitude at once dignified and nonchalant, characteristic of the sense of entitlement that informed aristocratic identity. One arm is cocked upon his hip, the other propped against the pedestal of the vase, as though signaling his ownership of the space and his right to relax therein. This pose had emerged as a touchstone for representing authority at the time and Kauffman, one of the most influential women artists of the 18th century, was a sought-after portrait painter for young aristocratic travelers participating in the Grand Tour like the subject of this painting.

More recently, American visual artist Kehinde Wiley, chose a similar pose in his notable painting Willem van Heythusen. Wiley’s lavish, larger-than-life images of African American men play on Old Master paintings. His realistic portraits offer the spectacle and beauty of traditional European art while simultaneously critiquing their exclusion of people of color. This portrait of Willem van Heythuysen references a 1625 painting of a Dutch merchant by Frans Hals, whose portraits helped define Holland’s Golden Age. Wiley’s model, from Harlem, New York, here takes the name of the original sitter from Haarlem, the Netherlands, whose pose and attitude he mimics. Despite the wide gold frame and the vibrantly patterned background with Indian-inspired tendrils encircling his legs, this subject’s stylish Sean John street wear and Timberland boots keep him firmly in the present and in urban America.

Kauffman’s portrait provides a historical reference point for understanding Wiley’s relationship to the European conventions as a means of subverting and challenging canonical exclusion and attitudes of white supremacy in present-day society.

(Left) Nkisi (Power Figure), 19th century, Kongo culture (Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Angola), wood, mirror, iron, cloth, shells, raffia, string, feathers, resin. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, purchased with funds from the Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Fund, 2000.5a–b. (Right) Untitled (from the Crossroads installation), 1989, Alison Saar (American, born 1956), wood, iron, tin. Virginia Musuem of Fine Arts, purchased with funds from the Sydney and Frances Lewis Endowment Fund, 92.233a-qqq

Kongo minkisi (plural; singular – nkisi) figures have long held a place of honor as the most potent of African art works. These objects, often carved in the likeness of a human figure, are invested with a sacred energy that can offer a person (or group of people) some sort of spiritual protection. There are many different types of minkisi and they can serve a variety of purposes such as identifying the cause of a disease, protecting against evil; they can be used to seal an agreement between disputing parties or to enforce a judgment on someone who has broken the law. Only a specially trained ritual practitioner, called an nganga (plural – banganga), can utilize the power of these objects on behalf of their clients. This type of nkisi figure is known as an nkondi, or oath-taking image.

The nails, pegs, blades and various items pierced through the figure all represent different lawsuits or arguments that have been litigated. The nganga takes the blade and drives it into the figure in order to seal a covenant. In addition, a nkisi figure is often packed with specially charged substances that help activate the object. This particular nkisi has substances sealed within the stomach, under the mirror-covered projection, as well as under the resin casing that crowns the head. Mirrors typically symbolize protection since a mirror’s reflection can show danger coming from any direction. Shown in an aggressive stance with a jutting chin, bared teeth, and holding a knife with a raised arm, this figure was meant to evoke fear in those individuals involved in settling a dispute, or some sort of legal agreement.

Alison Saar is a contemporary sculptor, mixed-media, and installation artist and her work Untitled (from the Crossroads installation) has taken on various meanings over the years, depending on the context of its surroundings. Despite the different interpretations, one very consistent observation about Saar’s sculpture is its strong connection to African sources, specifically minkisi figures (power figures that are typically found in parts of central Africa). Many of Saar’s artistic choices reflect her desire to honor these sacred ancient traditions from Africa. For example, Saar’s decision to use metal cladding, nails, and the industrial debris at the figure’s feet not only points to minkisi, but is also a nod to Ogun, the Yoruba orisa (deity) of iron (Yoruba Culture, Nigeria & Republic of Benin). Saar’s figure is elevated from the ground, standing on a metal platform, as if it were a statue on an altar. Interestingly, altars are considered spaces where this world and the spirit realm coincide, for the purpose of offering guidance, similar to minkisi.

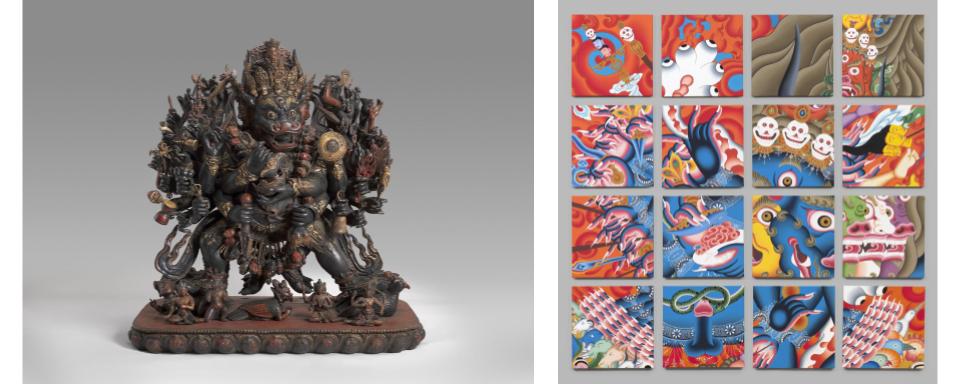

(Left) Vajrabhairava, 15th century or later, Sino-Tibetan, polychromed wood. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, purchased with funds provided by the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation and the Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Fund, 93.13a-oo. (Right) Luxation 1, 2016, Tsherin Sherpa (American, born Nepal 1968), acrylic on 16 stretched canvases. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 2017.195a-p

Also known as Yamantaka—Slayer of Yama, the Lord of Death—Vajrabhairava, the Lightning Terror, personifies the victory of spiritual wisdom over death. Ferocious and commanding, he is an ally of those seeking enlightenment. He tramples a host of figures symbolizing our delusions and attachments, and each implement in his thirty-four hands represents a different aspect of his spiritual knowledge used to destroy various obstacles to awakening. Vajrabhairava is, in fact, a wrathful emanation of the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, Manjushri, whose serene face appears at the sculpture’s apex.

Son and student of a master Tibetan painter, Tsherin Sherpa left his native Nepal in the 1990s for California. The title of the work Luxation 1, which was made after the catastrophic 2015 Nepal earthquake, means dislocation or displacement. It references that disaster’s devastation as well as the cultural dislocation experienced by the artist and all Tibetans. Sixteen jumbled pieces of an image are assembled into a composition whose small gaps are like chasms of missing information. Particular elements are recognizable, but their sum and true significance is unclear. Given its proximity to the wooden sculpture, however, many of these elements might seem familiar. Were one able to fill in all the omitted pieces, it would become clear that this image too is Vajrabhairava, whose role is to help us conquer our fear of death.

Produced to accompany the exhibition, "Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic," this video series features the artist himself discussing his background, work, process, philosophy, and art historical influences.

Hear and see what major artists have to say about their works and concepts in their own words. These concise videos–2 to 3 minutes–are historic interviews recorded one-on-one by VMFA in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Tsherin Sherpa visits Tsherin Sherpa: Spirits at VMFA in 2022 along with Dr. John Henry Rice, VMFA's E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Curator of South Asian and Islamic Art.