African American Art at VMFA

Discover VMFA's growing collection of works by African American artists!

Overview

VMFA has a growing collection of works by African American artists, including those highlighted here. The collection features work by early American and modern and contemporary artists. With such a vast arc across time, these works collectively underscore dramatic shifts in the artistic, social, and political landscape and their impact upon creative expression. This guide represents only a fraction of the works on view by African American artists. To explore more of VMFA’s holdings please visit the African American Art Featured Collection page.

Please visit the Modern and Contemporary Art and African Art Collection pages to explore more works that represent the wider African Diaspora and VMFA’s commitment to presenting artists of color from across the globe.

21st CENTURY ART - Atrium

A Small Band, Glenn Ligon

“I had to, like, open the bruise up and let some of the blues . . . bruise blood come out to show them.”—Daniel Hamm

Ligon has become one of the most influential artists of his generation. Working in a variety of media, from painting to neon sculpture and installations, he presents a raw examination of culture and social identity mediated through the lens of history, literature, iconic works of art, and material culture.

The title of this work is extracted from a quote by Daniel Hamm, imprisoned as part of the famed “Harlem Six” or “Blood Brothers,” a group of young black men wrongly accused of murder in 1965. Hamm and four other members of the group—Wallace Baker, William Craig, Ronald Felder, and Walter Thomas—were eventually exonerated. Robert Rice however remains incarcerated, serving a life sentence. In a statement shared a few days following his release from police custody, Hamm spoke publicly about the brutality he experienced at the hands of prison guards.

Hamm’s quote is particularly poignant against the current social landscape in which incidents of police violence against and wrongful incarcerations of young African American men have continued to rise.

AMERICAN ART - 2nd floor

Doubled-handled Jug, David Drake

One of only twenty-nine identified, signed, and dated poem wares by enslaved potter David Drake, this jug evidences Drake’s ability to read and write. Although a few slaves were taught to read in the early decades of the 19th century, the practice increasingly became illegal in the period preceding the Civil War. Drake’s overt use of writing—and his owner’s acceptance of it—was a defiant gesture that proclaimed his identity during an era when his individual status was not acknowledged.

Tired, Samella Sanders Lewis

In 1941 Samella Sanders Lewis accompanied her professor and mentor, Elizabeth Catlett, when the two transferred from Dillard University in New Orleans to Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in Virginia. Lewis adopted Catlett’s interest in sculptural representations of African American women in everyday life. As a college student herself, the artist likely empathized with the weary expression of the sculpted woman, who slumps sideways while reading a large book. Tired was first displayed at VMFA in 1944 in an exhibition of artwork by Virginia college students, in which the sculpture was singled out for praise.

Dressing Bureau, Thomas Day

This dressing bureau demonstrates Thomas Day’s unique variation on the Classical Revival, a furniture and architectural style prevalent throughout the United States between 1830 and 1860. While the form draws on the published designs of Baltimore architect John Hall, Day enhanced its basic “pillar and scroll” motifs in the bureau’s stylized, somewhat whimsical mirror supports. A closely related bureau was produced by Day as part of a suite commissioned by North Carolina governor David Reid.

Portrait of Mrs. Elizabeth West and Her Daughter Mary Ann West, Joshua Johnson

The artist Joshua Johnson was born into slavery near Baltimore, Maryland, around 1763, the son of an enslaved woman and a free white man, George Johnston (Joshua infrequently spelled his surname with a t), who later purchased his son and freed him around age twenty-one. Johnson trained as a blacksmith, but it is unknown how he learned to paint. By 1796 he listed his profession in a city directory as “portrait painter” and two years later advertised in the newspaper as a “self-taught genius.”

Softly modeled against a dark background, Elizabeth and Mary Ann West are depicted in highly fashionable empire gowns. The young Mary Ann holds a woven basket of roses in one hand, while in the other she holds two roses originating from the same stem, symbolic of the Elizabeth and Mary Ann’s connection as mother and daughter (red and pink roses historically designate love and grace, respectively). Their overlapping bodies and the touching of their limbs, found pervasively in contemporary American portraiture suggests the era’s new etiquette of relaxed mores regarding displays of affection.

Idyll of Virginia Mountains, 1945, George H. Ben Johnson (American, 1888-1970), Oil on canvas, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Katherine Rhoads Memorial Fund, 45.10.3

Idyll of Virginia Mountains, George H. Ben Johnson

Johnson, who earned his living in Richmond, Virginia, as a mail carrier, taught himself to draw and paint. In the 1910s, he penned dozens of editorial cartoons for the city’s leading black newspaper, many denouncing the inequities of Jim Crow segregation. As a painter, Johnson focused primarily on biblical and historical subjects, but he also produced still lifes and landscapes – Idyll of Virginia Mountains being one of his most lyrical. Here he locates the viewer high up on a craggy promontory of the state’s famed Blue Ridge range, defined in painterly strokes of turquoise, violet gray, and brown. In places, touches of peach pigment suggest the glancing rays of the setting sun.

During the anxious war years of 1944 and 1945, VMFA quietly crossed racial barriers by acquiring its first artwork by African Americans. Jacob Lawrence’s Subway-Home from Work (44.18.1) and Leslie Bolling’s Cousin-on-Friday (44.2.1) were received as gifts, while this light-filled canvas was purchased from the museum’s annual Virginia artist’s exhibition.

Christ and His Disciples on the Sea of Galilee, Henry Ossawa Tanner

To capture the mystery and drama of the story of Christ calming the waters, Tanner created this small but powerful image. Frightened passengers brace themselves against the roiling sea in the bottom of the boat. Before them, a nearly transparent figure of Jesus stands with outstretched arms as distant clouds begin to break.

The Pittsburgh-born Tanner had exhibited to great acclaim at the prestigious Paris Salon for almost a decade by the time he produced this scene. As an African American artist, his professional acceptance in the United States was hampered by racial restrictions. “I cannot fight prejudice and paint,” he announced before departing for Europe in 1891.

Booker T. Washington, Richmond Barthé

A leading figure of the 1920s New Negro Movement, otherwise known as the Harlem Renaissance, the Mississippi-born Richmond Barthé studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago before relocating to Manhattan in 1929.

These striking busts—of famed political leader and educator Booker T. Washington and acclaimed Black poet Paul Laurence Dunbar—belong to Barthé’s 1928 portrait series of eminent African Americans, which also included depictions of the artist Henry Ossawa Tanner and historical political leader Toussaint L’Ouverture. Both works may have been featured in the exhibition American Negro Artists, sponsored by the Harmon Foundation. Established in 1922, the foundation was the first to support and promote the work of African American artists through juried exhibitions.

Hiawatha's Marriage, modeled 1866, carved 1870, Edmonia Lewis (American/Mississauga Ojibwe, 1844-1907), marble. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, J. Hardwood and Louise B. Cochrane Fund, 2024.26

Hiawatha’s Marriage, Edmonia Lewis

Edmonia Lewis was the first internationally acclaimed African American and Indigenous (Mississauga Ojibwe) sculptor. The source for this work is Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1855 enormously popular epic poem “The Song of Hiawatha.” Lewis’s response to Longfellow’s verse visualizes a passage from part X of the poem in which Hiawatha and Minnehaha “clasp … hands,” symbolizing not only their marriage but also the peace between their respective tribes, the Ojibwe and the Dakota.

Hiawatha’s Marriage merges Westernized idealism and realism—the latter through the hair styles, arrows and quiver, and eagle feathers and the former by way of the generalized facial features, pronounced brows, high foreheads, and the gaze of the figures’ faces. Lewis carefully incised intricate, symmetrical patterns into the couple’s moccasins, Minnehaha’s shawl, and Hiawatha’s quiver.

The moccasins, in particular, may reference Ojibwe or Dakota beadwork motifs, both of which are known for balanced, vibrant floral designs.

Catfish Row, Jacob Lawrence

In 1947 the celebrated modernist Jacob Lawrence received a commission from Fortune magazine to depict African American life in the so-called Black Belt, a broad agricultural region of the Deep South. The artist spent a few weeks that summer traveling to Memphis, Vicksburg, and New Orleans, as well as various communities in Alabama. Catfish Row is one of ten temperas resulting from Lawrence’s journey, all painted on his return to New York. This dynamic painting, with its overall mood of abundance and pleasure, depicts the shared preparation and consumption of food in Black communities that offered some respite from the hardships of racial discrimination in the postwar years.

Portrait of a Woman in a Windsor Chair, Joseph Delaney

Much like the painting practice of Joseph Delaney’s older brother Beauford, Joseph infuses his work with a psychological charge that comes from the sitter’s gaze. Seated in a Windsor chair, the young woman stares outside of the canvas with her weight shifted to her right side as her hand drapes over the curved arm of the chair. The seated form, treatment of the hands, and unflinching but sympathetic expression suggest the woman as an accessible, thoughtful, and empathetic individual. Her gaze also suggests a woman who is both relaxed and considerate. Her relative proximity to the viewer contributes to the heightened sense of palpable humanity and dignity.

21st century art - 2nd floor

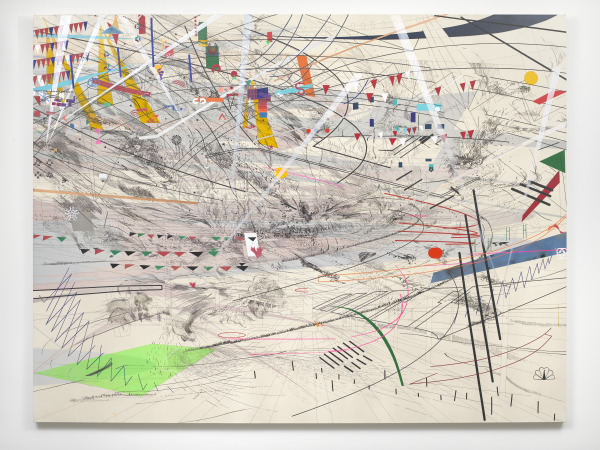

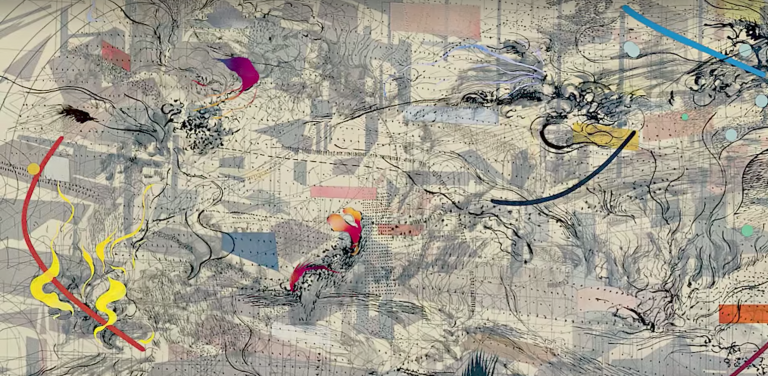

Stadia III, Julie Mehretu

Mehretu’s monumental paintings address contemporary themes of power, colonialism, and globalism with dramatic flair. She adopts imagery from architecture, city planning, mapping, and the media. At the same time, her bold use of color, line, and gesture makes her works feel like personal expression.

Stadia III belongs to a series of three Stadia paintings dealing with the theme of mass spectacle. Conceived in the wake of the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, the series reflects Mehretu’s fascination with television coverage that transformed the war into a kind of video game—as many at the time commented—and in the spectrum of nationalistic responses that she witnessed during travels to Mexico, Australia, Turkey, and Germany. The series also reflects her interest in the international buildup to the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens.

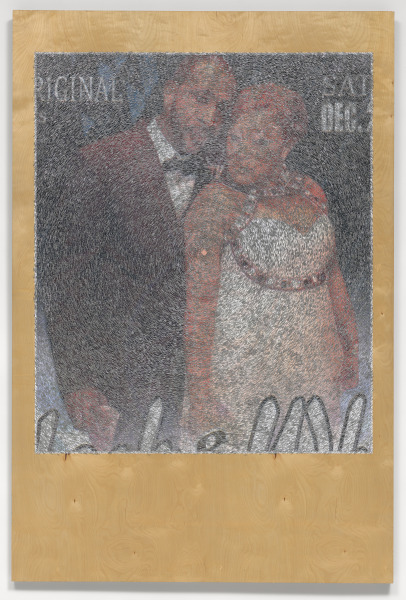

Iack & Wh, Wilmer Wilson IV

Wilmer Wilson IV is critically recognized for his performative investigations into the marginalization of Black bodies. The artist refers to his performances as “ephemeral sculptures,” as he often transforms large quantities of ordinary objects and urban detritus into objects. The resulting works are sometimes temporal and other times finished objects born from these performances.

Iack & Wh takes its title from the fragmental language of the featured image. Wilson found the torn poster while walking in his Philadelphia neighborhood. The picture, truncated and fragmented, was then subjected to the Wilson’s surface treatment in which he superimposed hundreds of thousands of staples, nearly obliterating it. Like a lenticular image, the work alternates between legibility and obscurity as it both reveals and hides the picture from various vantage points.

Wilson sees this process of accumulation as an act of resistance; the subjects are protected from being objectified. The punctuated image also evokes the nkisi in classical African sculpture, suggesting the repulsion of evil forces and driving out of sickness of not only the individuals, but the communities in which they live.

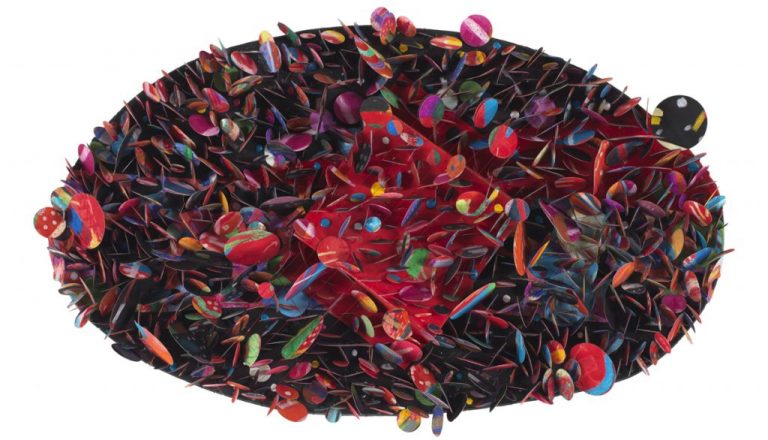

Untitled, Howardena Pindell

This stenciled painting is one of Pindell’s first large-scale works to include hole-punched circles directly on the surface. The few scattered dots foreshadow a significant change in her work—hole-punched circles that cover entire surfaces of her canvases.

Untitled (Cylindrical Lens), 2023, Fred Eversley (American, born 1941), cast polyurethane. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment, 2024.1

Untitled (Cylindrical Lens), Fred Eversley

Fred Eversley originally trained as an engineer but in the 1960s shifted his focus to visual arts creating a technique to spin-cast liquid resin to create free-standing sculptures. His training as an engineer remains evident in his sculptural forms like Untitled (Cylindrical Lens) which suggests the shape of a parabola, a form that concentrates all energy (sound, movement, and light) into a single focal point. The internal reflections and refractions of light seen in the piece are as important as the shape of the sculpture itself. Eversley is using new materials and techniques in this work; liquid tint instead of industrial dyes, polyurethane resin instead of polyester resin, and these works are not spun in motion but rather cast to create plano-convex lenses, or objects that have one spherical surface and one flat surface. This work demonstrates growth from the early to late periods in Eversley’s artistic practice as well as how his interest in both form and color have changed throughout his career.

Untitled (from the Crossroads installation), Alison Saar

Alison Saar is a contemporary sculptor, mixed-media, and installation artist and her work Untitled (from the Crossroads installation) has taken on various meanings over the years, depending on the context of its surroundings. Despite the different interpretations, one very consistent observation about Saar’s sculpture is its strong connection to African sources, specifically minkisi figures (power figures that are typically found in parts of central Africa). Many of Saar’s artistic choices reflect her desire to honor these sacred ancient traditions from Africa. For example, Saar’s decision to use metal cladding, nails, and the industrial debris at the figure’s feet not only points to minkisi, but is also a nod to Ogun, the Yoruba orisa (deity) of iron (Yoruba Culture, Nigeria & Republic of Benin). Saar’s figure is elevated from the ground, standing on a metal platform, as if it were a statue on an altar. Interestingly, altars are considered spaces where this world and the spirit realm coincide, for the purpose of offering guidance, similar to minkisi.

Great Hall - Level 2

No Way But This, 2013, Fred Wilson (American, born 1954), Murano Glass, Edition of 6, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment, 2024.20

No Way But This, Fred Wilson

Since early in his career, Fred Wilson has explored the intersections of history, art, and culture. While his earlier works focused on museum collections and art’s critical role in the framing of perceptions and the othering of non-European Americans, Wilson’s more recent work takes on expressly European tropes to reframe ideas of “otherness.” Since 2001, Wilson has worked with glassblower Dante Marioni and factories in Murano, Italy, to explore the phenomenon of Murano glass traditions dating back to the 18th century. Through this process, Wilson embraced creating images in black glass to interpret Blackness both historically and contemporarily in Italian and global culture.

With No Way But This, Wilson challenges such tropes by utilizing the hallmark of Venetian aesthetics, Murano glass. Traditionally, glass chandeliers made in this region were white or pastel colors; Wilson’s was the first one to be made using the color black. This chandelier is one in a five-part series representing the five acts of William Shakespeare’s 17th century play The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice. This work embodies the climax of the play when Othello, a Moor and a general in the Venetian Army, murders his wife Desdemona by strangulation after the character Iago lies about her being an adulteress. Chalice-inspired forms throughout the chandelier reference Othello’s original plan to kill Desdemona by poisoning her drink.

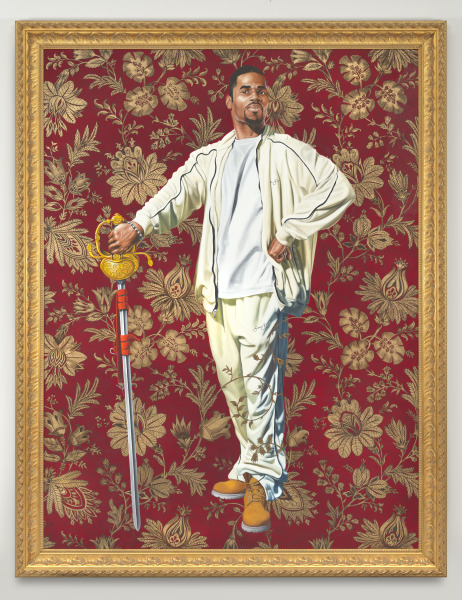

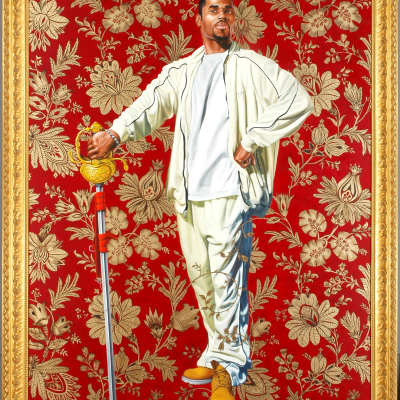

Willem van Heythuysen, Kehinde Wiley

Wiley’s lavish, larger-than-life images of African-American men play on Old Master paintings. His realistic portraits offer the spectacle and beauty of traditional European art while simultaneously critiquing their exclusion of people of color.

Wiley’s Willem van Heythuysen quotes a 1625 painting of a Dutch merchant by Frans Hals, whose bravura portraits helped define Holland’s Golden Age. Wiley’s model, from Harlem, New York, here takes the name of the original sitter from Harlem, the Netherlands, whose pose and attitude he mimics. Despite the wide gold frame and the vibrantly patterned background whose Indian-inspired tendrils encircle his legs, this subject’s stylish Sean John street wear and Timberland boots keep him firmly in the present and in urban America.

Artists Interviews

Howardena Pindell @ VMFA

56:45A conversation with the renowned abstract, multidisciplinary artist about her life and her work with Valerie Cassel Oliver of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and Naomi Beckwith of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago.

Chester Higgins @ VMFA

1:07:11Photographer Chester Higgins sees his “life as a narrative and [his] photography as its expression.” Friday, Feb 16, 2018.

Julie Mehretu @ VMFA

4:12Artist Julie Mehretu talks about the concepts, processes, and implications of her "Stadia" series, including "Stadia III" in VMFA's permanent collection.

Alison Saar @ VMFA (1993)

2:37Hear and see what major artists have to say about their works and concepts in their own words. These concise videos–2 to 3 minutes–are historic interviews recorded one-on-one by VMFA in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Artist Talk | LeRoy Henderson

1:04:08LeRoy Henderson discusses his life and work documenting American protest culture with Dr. Sarah Eckhardt, Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, on Thursday, February 16, 2017 at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Hank Willis Thomas @VMFA

4:34American artist Hank Willis Thomas discusses his work and the construction of black identity through popular culture.

The interview was conduced by John B. Ravenal (Syndey and Frances Lewis Family Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art), VMFA.

Lorna Simpson @ VMFA

3:04Hear and see what major artists have to say about their works and concepts in their own words. These concise videos–2 to 3 minutes–are historic interviews recorded one-on-one by VMFA in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Radcliffe Bailey @ VMFA

5:14Artist Radcliffe Bailey talks about his artistic process and what he hopes his art conveys. Come see "Vessel" in VMFA's permanent collection.

Robert Pruitt @VMFA

3:50American artist Robert Pruitt discusses his inspirations, his process, and elements of the absurd in this artist talk.

Howardena Pindell @ VMFA

56:45Chester Higgins @ VMFA

1:07:11Julie Mehretu @ VMFA

4:12Artist Talk | LeRoy Henderson

1:04:08Lorna Simpson @ VMFA

3:04Robert Pruitt @VMFA

3:50Additional Resources

Discover more ways to connect with the art by African American Artists on Learn.

Audio Guide: African American Artists

For families:

Little Eyes Look: Boys with Banana by the Window