Women Artists at VMFA

VMFA has a growing collection of works by women artists, including those listed here, from across time and place. These works underscore the many contributions and profound impact of female artists and provide a visual record of how they have been integral to shaping the narrative of art, influencing styles, themes, and movements across the centuries.

AMERICAN GALLERIES - Level 2

Tired, 1943, Samella Sanders Lewis (American, 1924-2022), painted plaster. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, gift of Elizabeth Cornellia Davis, 2023.793

Tired, Samella Sanders Lewis

In 1941 Samella Sanders Lewis accompanied her professor and mentor, Elizabeth Catlett, when the two transferred from Dillard University in New Orleans to Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in Virginia. Lewis adopted Catlett’s interest in sculptural representations of African American women in everyday life. As a college student herself, the artist likely empathized with the weary expression of the sculpted woman, who slumps sideways while reading a large book. Tired was first displayed at VMFA in 1944 in an exhibition of artwork by Virginia college students, in which the sculpture was singled out for praise.

The Flint Flood, 1948, Lucienne Bloch (American, born Switzerland, 1909-1999), egg tempera on Masonite. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, J. Harwood and Louise B. Cochrane Fund for American Art, 2024.11

The Flint Flood, Lucienne Bloch

A muralist, printmaker, sculptor, glass artist, illustrator, and educator, Lucienne Bloch began her artistic training at the Cleveland Institute of Art in 1924–25, continuing her studies at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. This painting likely depicts the Flint, Michigan, flood of April 4–11, 1947, which was caused by a combination of melting snow and persistent thunderstorms. At right, atop a partially cropped election campaign poster, is signage for the arcade and activity center Playland; at left is signage for two Coney Island hot dog eateries; above that zone is a backwards, cropped Chevrolet sign. The emphasis on signage is in keeping with the artist’s background. Bloch had earlier designed protest posters with her husband, who was a sign-maker in Flint for Buick.

Mother and Child, Bessie Potter Vonnoh

Vonnoh, like her colleague Mary Cassatt, cultivated a successful career producing sculptures of upper-class women at different stages of life. Images of mother and child, like this one, were among her most popular works and were reproduced in numerous castings. Here the artist’s modeling skills are revealed in the controlled naturalism of the figures and the graceful treatment of the drapery.

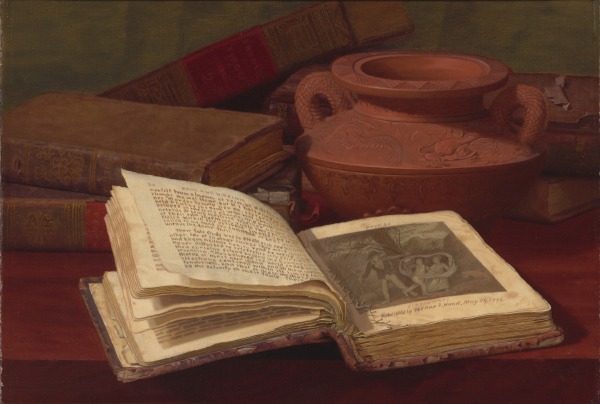

Books and Pottery Vase, Claude Raguet Hirst

At the turn of the 20th century, Hirst’s meticulous still lifes held such public appeal that, as one critic wrote, “they are apt to be hanging crooked…as people take them down so many times to hold them and look at them.” While touching art in galleries was discouraged then, as it is now, close examination was precisely the response that Hirst sought. The painter was one of a handful of Gilded Age artists – and the only female (her first name was shortened from Claudine) – to gain critical acclaim for illusionary imagery.

In this painting, Hirst presents an arrangement of old books and a ceramic pot with Asian motifs. She draws the eye to a brightly lid, opened book rendered with such precision that words can be read from its pages. The worn volume was one of the artist’s favorites: a 1795 English translation of Bernardin de Saint-Pierre’s romantic novel, Paul and Virginia. The painting’s frame – contemporary with the canvas but not original – offers its own visual surprise. The beautiful curling grain is actually painted. One trompe-l’oeil triumph supports the other.

Child Picking a Fruit, Mary Cassatt

Child Picking a Fruit merges the subject that made Mary Cassatt famous—a young woman (possibly a mother) and child—with her more ambitious examination of “modern woman,” a topical theme at the turn of the 20th century as the women’s suffrage movement gained momentum. The image derives from the artist’s now-lost Modern Woman mural commission, produced for the Woman’s Building of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. For this prestigious world’s fair, Cassatt presented her allegorical subject in a three-panel lunette. The large central panel, Young Women Plucking the Fruits of Knowledge, featured women of different ages, clad in contemporary dress and communally harvesting fruit from an orchard.

Four Directions/Stillness, Kay Walkingstick

In Four Directions/Stillness, Kay WalkingStick uses the diptych format to make clear distinctions between physical and spiritual forms of existence while also conforming their invariable connectedness. Her landscapes, as well as her abstractions, are a kind of memory documentation. The cross in the center of the abstract panel pays respect to a collective human memory, notably one of the most recognizable motifs in several Native American cultures, signifying the four cardinal directions. The landscape side represent a personal memory of Bandolier National Monument in New Mexico. IT is typical of WalkingStick’s process, in which she creates numerous sketches of a place but ultimately produces an image based largely on her memories and associated emotions.

Hiawatha's Marriage, modeled 1866, carved 1870, Edmonia Lewis (American/Mississauga Ojibwe, 1844-1907), marble. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, J. Hardwood and Louise B. Cochrane Fund, 2024.26

Hiawatha’s Marriage, Edmonia Lewis

Edmonia Lewis was the first internationally acclaimed African American and Indigenous (Mississauga Ojibwe) sculptor. The source for this work is Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1855 enormously popular epic poem “The Song of Hiawatha.” Lewis’s response to Longfellow’s verse visualizes a passage from part X of the poem in which Hiawatha and Minnehaha “clasp … hands,” symbolizing not only their marriage but also the peace between their respective tribes, the Ojibwe and the Dakota.

Hiawatha’s Marriage merges Westernized idealism and realism—the latter through the hair styles, arrows and quiver, and eagle feathers and the former by way of the generalized facial features, pronounced brows, high foreheads, and the blank gaze of the figures’ faces. Lewis carefully incised intricate, symmetrical patterns into the couple’s moccasins, Minnehaha’s shawl, and Hiawatha’s quiver. The moccasins, in particular, may reference Ojibwe or Dakota beadwork motifs, both of which are known for balanced, vibrant floral designs.

East Asian Galleries - Level 2

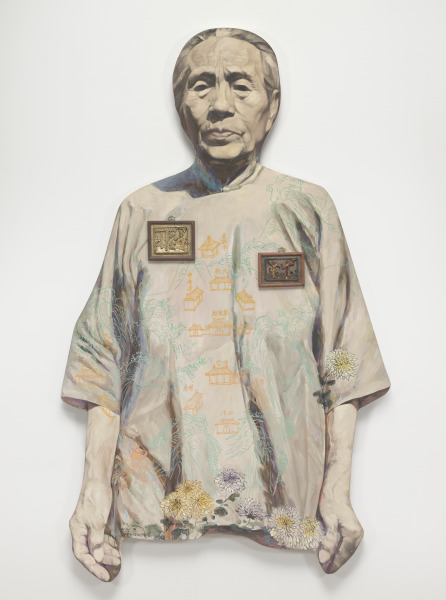

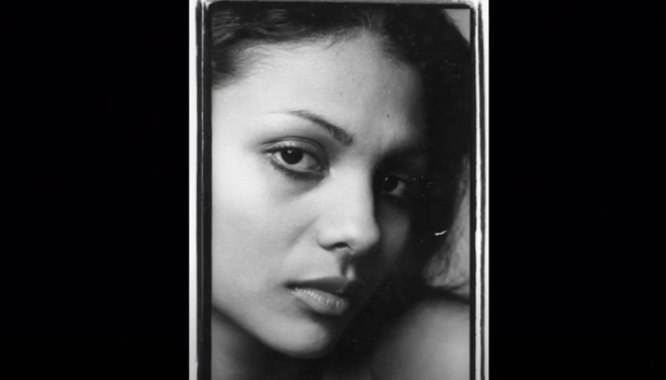

Grandma, Hung Liu

Hung Liu, considered one of the most important Chinese American artists, devoted her life to exploring subjects that reflect history, memory, and the lives of ordinary people. Liu moved to the United States in 1984 to pursue graduate studies at the University of California, San Diego. This portrait was created in two phases. First in 1993, Liu worked from a historical photograph of her grandmother, Wang Jushou (1890–1979). The monumental scale, dignified pose, and serene appearance all suggest the figure’s inner power and her importance to the artist. Twenty years later, in 2013, Liu added to the blouse the scenes of Mount Qianshan in northeast China, including trees, rocks, and two Zen Buddhist temples. These details pay homage to Liu’s grandfather, Liu Weihua (1894–1962), a scholar and lay Buddhist who committed his life to studying Mount Qianshan’s cultural history. The wooden panels attached to the chest depict traditional performing scenes. With compassion and insight, Liu conveys her intent of empowering working women to honor their contributions to family and society.

EUROPEAN GALLERIES - Level 2

Portrait of the Comte de Vaudreuil, Elisabeth-Louise Vigée-Lebrun

Vigée-Lebrun, daughter of a Paris pastelist, was a successful portrait painter from the age of fifteen. In 1779 she was called to court to paint Queen Marie-Antoinette’s portrait; she quickly became the queen’s favorite artist. Like the Comte de Vaudreuil, Vigée-Lebrun fled France at the beginning of the revolution, but was later invited to return, which she did briefly in 1802 and permanently in 1810. The Comte de Vaudreuil was a wealthy plantation owner who lived so grandly that he was cited as one of the causes of the French Revolution. A noted art collector, he once owned VMFA’s Finding of the Laocoön by Hubert Robert.

Portrait of A Lady of the Gonzaga or Sanvitale Family (possibly Isabella Gonzaga), Lavinia Fontana

Lavinia Fontana was a renowned Mannerist painter during the Late Renaissance period, and one of the first women artists in Italy to gain public recognition alongside her male colleagues. By the 1580s, her portraits were in demand among the noble families of northern Italy. Portraits such as this one often played a crucial role in the traditions surrounding aristocratic martial engagements. Fontana carefully devises every element of this elegant composition to emphasize her sitter’s luxurious ornamentation as well as her Catholic piety and chastity, ensuring that this bride-to-be is represented as a paragon of both wealth and virtue. The young woman is dressed in an extravagant amount of gold, jewels, precious stones, and pearls, and the foregrounds each piece with an indulgent degree of technical virtuosity. Although the sitter’s identity remains uncertain, recent research has proposed that this is probably a representation of a young Isabella Gonzaga, duchess of Sabbioneta (1556-1637), an influential member of a princely family from Mantua.

Full-length portrait of William Henry Lambton (1764-1797) in a Van Dyck style costume, Angelica Kauffman

Angelica Kauffman was one of the most influential women artists of the 18th century. After eventually settling in Rome, she became a sought-after portrait painter for the young aristocratic travelers participating in the Grand Tour. This painting presents the quintessential characteristics of the Grand Tour portrait tradition. The sitter, a wealthy member of the British Parliament traveling through Italy at the time, is dressed in a fancy and anachronistic 17th-century costume. He stands on a terrace that opens onto a mountainous landscape. Next to him, a depiction of the Medici Vase, one of the most celebrated pieces still extant from the Greek classical period (AD 1st century), shows his cultural interest as an educated traveler and art connoisseur.

EVANS COURT - INDIGENOUS AMERICAN ART- Level 2

Butterfly Whorl, Susan Point

In Butterfly Whorl, Susan Point, a Coast Salish artist from Musqueam First Nation, connects flowing lines in a composition that uses Coast Salish designs like circles and trigons to render the titular creature. The work’s form pays homage to wooden spindle whorls used in Coast Salish weaving, a culturally significant artform traditionally done by women. Coast Salish weavers use whorls that, like Butterfly Whorl, are often intricately carved with designs or images, to spin their own yarn. The yarn is then women to produce vibrant blankets that, through a Coast Salish worldview, confer spiritual protection and are imbued with the stories and understandings of their makers. When Point first began making largescale sculpture, it was a creative field typically reserved for men. Point has since embraced the sculptural medium to experiment with ancestral Coast Salish visual languages while honoring the practices of Coast Salish women artists.

Jar with Floral Design, Camille Bernal

Both the design and materials of this jar by Camille Bernal pay homage to New Mexico, particularly the Taos Peublo area where the artist grew up. Twenty-four layers of white slip, polished to a matte finish, create a luminous surface on which to paint graceful abstract flowers. The delicate blossoms are a call for rain, so crucial to life in the arid region. The red micaceous paint on the inside and on some of the flowers is a remembrance of earlier Taos potters, who were known for their own micaceous pottery.

Puttawus, Raven Custalow

Many nations of the Eastern Woodlands made and wore feather cloaks, or mantles. These garments were worn in various ways: draping only one shoulder, covering the entire body, or extending from the shoulder to the ground. Colors and weaving techniques differed based on the feathers used and how they were attached to the backing. Archaeological records show that these mantles are a uniquely Eastern Woodlands art form, documented by early colonizers of North America. However their physical existence is scant, with only fragments surviving in burial sites.

Raven Custalow is a Mattaponi tribal citizen and CEO of Eastern Woodland Revitalization, whose mission is to revitalize cultural practices specific to Eastern Woodland Indigenous people. She is seeking to revitalize the art of feather weaving not only among Mattapoint people but also to other regions in Virginia.

Large Pot, Christine Custalow

Christine Custalow is descended from both Rappahannock and Mattaponi peoples. She learned pottery making from her mother and continues to create works with the same traditional methods. Her low-fire “baking” process results in rich, luminous surfaces with organic tonal variation. Custalow uses the pinch-pot building process for smaller vessels and the coil method for larger ones. Most of her pots are burnished to a high shine using a smooth rock or a small piece of deer antler as a polishing tool. Custalow also employs other methods of surface embellishment. This example uses decorative elements such as feathers and beads attached to the vessel after it has been fully fired.

EVANS COURT - AFRICAN ART - Level 2

ibala leSindebele (Ndebele Design), Esther Mahlangu

In 2014 VMFA commissioned Esther Mahlangu to create two large-scale paintings to form a vibrant gateway for the African Art Galleries. The most renowned contemporary artist among South Africa’s Ndebele people, Mahlangu has transformed the art of mural painting from its historic tradition of designs on the exterior of rural houses to projects created in a global contemporary art context. Her career was propelled in 1989 when she was invited to participate in the landmark Magiciens de la Terre exhibition in Paris. In 1991 BMW commissioned her to paint a car for their Art Car program; to date, she is the only African and only female artist included in this project.

Painted on linen, these works will survive indefinitely, whereas murals painted directly on building surfaces can be imperiled by renovation, overpainting, or degeneration from weather. Indeed, some of Esther Mahlangu’s most significant international mural projects now exist only through photographic documentation.

Mellon Collection - Level 2

The Jetty, Isle of Wight, Berthe Morisot

Morisot traveled to England with her husband during the summer of 1875. This painting of the West Cowes region of the Isle of Wight is one of several works she completed during that trip. Morisot wrote to her sister Edma of the difficulty she faced while attempting to depict this lively area of the island: “It is the prettiest place for painting-if one had any talent…People come and go on the jetty, and it is impossible to catch them…There is extraordinary life and movement, but how is one to render it?”

When Morisot exhibited nineteen paintings from the trip at the 1876 Impressionist exhibition, the critical reception was ambivalent. One reviewer from L’Echo Universel admitted that the Isle of Wight was immediately recognizable in certain canvases, but he was confused by the artist’s patently Impressionistic style, complaining that a close examination of the painting’s compositional details revealed “the presence of monstrous beings, incoherent dabs and crazy prospective,” which he considered destructive to the illusion of the landscape. Morisot’s experimental approach to landscape painting was better understood and appreciated by the collector of modern art Victor Choquet (1821-1891), who purchased the work in 1879.

MID TO LATE 20th CENTURY GALLERIES - Level 2

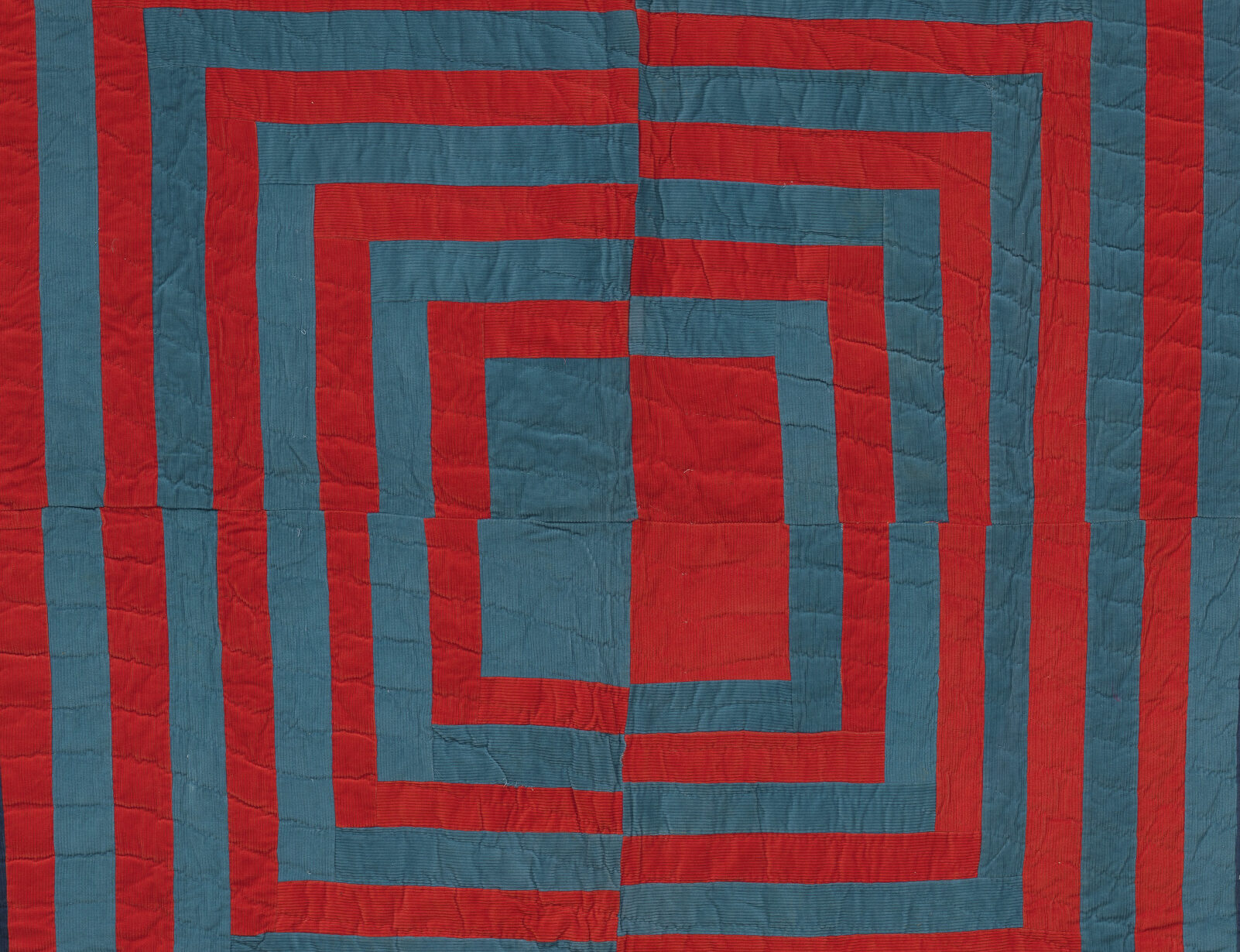

"Stacked Bricks" in columns with borders on two sides, Nell Hall Williams

Nell Hall Williams was born near Gee’s Bend, where her mother, Pearlie Hall, was raised. Before she reached her teenage years, Williams was making her quilts from cast-off clothing and bleached flour sacks. After amassing a number of quilts as an adult, Williams lost most of them in a house fire. This quilt is one of the few remaining from this early period of the artist’s life. In her use of the “Stacked Bricks” pattern, Williams plays upon the silk’s lush texture to generate maximum visual effect. The composition of this work clearly displays her knowledge of color dynamics. Williams’s bold use of geometric forms brings a sense of improvisational movement to the work and offers a great visual exchange with Donald Judd’s Meter Boxes, seen to the left of this quilt.

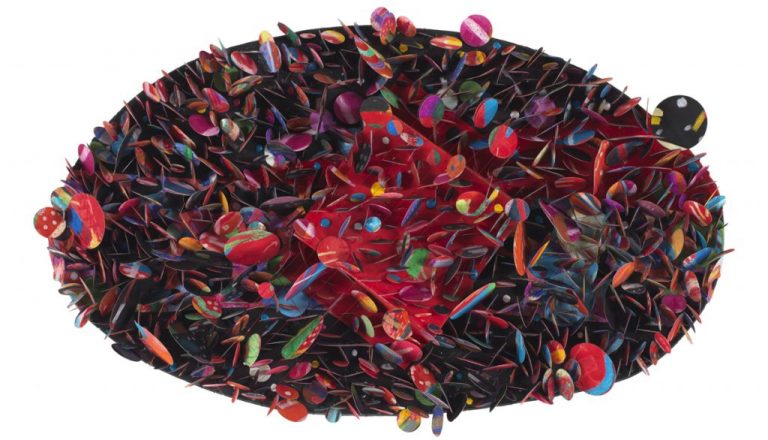

Untitled, Howardena Pindell

This stenciled painting is one of Pindell’s first large-scale works to include hole-punched circles directly on the surface. The few scattered dots foreshadow a significant change in her work—hole-punched circles that cover entire surfaces of her canvases.

No. 3 - 1957, Hedda Sterne

“New York seemed to me at the time like a giant carousel in continuous motion—on many levels—lines approaching swiftly and curving back again forming an intricate ballet of reflections and sounds.”—Hedda Sterne

Sterne grew up in the midst of the Romanian avant-garde in the 1920s. She traveled to Paris frequently in the 1930s, immersing herself in Surrealism before relocating to New York in 1941. There she quickly became active in the circle of exiled European artists and the younger generation of American artists who later became Abstract Expressionists. In the early 1950s, Sterne began painting with the newly invented aerosol spray, discovering that its speed and ease of movement paired with the paint’s diffuse, blurred edges effectively translated the sensation of the pulsating city environments she depicted.

Bull, Elaine de Kooning

While many Abstract Expressionists eschewed recognizable subject matter altogether, Elaine de Kooning frequently blurred the line between abstraction and figure painting. She used energetic, loose brushstrokes to paint dynamic portraits of figures as diverse as the dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham and President John F. Kennedy. In 1957 she was a visiting professor at University of New Mexico in Albuquerque and took the opportunity to travel throughout the West. After a visit to Juárez, Mexico, where she attended bullfights, the bull became a central motif in her painting for many years.

Forsythia and Pussy Willows Begin Spring, Alma Thomas

Forsythia and Pussy Willows Begin Spring provides an iconic example of Alma Thomas’s widely acclaimed painting style of the 1960s and 1970s. An avid gardener, Thomas frequently painted the flowers from her colorful backyard. Here, she included the bright yellow forsythia blossoms and pussy willow catkins that serve as early signs of spring. Although abstracted, Thomas’s work evokes the beauty of nature through her precise dabs of vibrant color placed in a successive vertical grid.

Mother Goose Melody, Helen Frankenthaler

“The painter makes something magical, spatial, and alive on a surface that is flat and with materials that are inert. That magic is what makes a painting unique and necessary. Painting, in many ways, is a glorious illusion.”—Helen Frankenthaler

In Mother Goose Melody, Frankenthaler combines the gestural splashes and drips of Abstract Expressionist painting with the innovative stained-canvas technique she helped pioneer in 1952. The array of colors, shapes, and lines makes this composition rhythmic and dynamic. The spiraling red form on the right counters the dense area of color on the left, while the broad yellow band stretching across the bottom unites both. The artist noted that the three brown shapes could refer to herself and her two sisters, and that the red and black lines “made a sort of stork figure—the whole thing had a nursery-rhyme feeling.”

21st CENTURY GALLERIES - Level 2

Untitled (from the Crossroads installation), Alison Saar

Alison Saar is a contemporary sculptor, mixed-media, and installation artist and her work Untitled (from the Crossroads installation) has taken on various meanings over the years, depending on the context of its surroundings. Despite the different interpretations, one very consistent observation about Saar’s sculpture is its strong connection to African sources, specifically minkisi figures (power figures that are typically found in parts of central Africa). Many of Saar’s artistic choices reflect her desire to honor these sacred ancient traditions from Africa. For example, Saar’s decision to use metal cladding, nails, and the industrial debris at the figure’s feet not only points to minkisi, but is also a nod to Ogun, the Yoruba orisa (deity) of iron (Yoruba Culture, Nigeria & Republic of Benin). Saar’s figure is elevated from the ground, standing on a metal platform, as if it were a statue on an altar. Interestingly, altars are considered spaces where this world and the spirit realm coincide, for the purpose of offering guidance, similar to minkisi.

Wood Picture, Mildred Thompson

Mildred Thompson began experimenting with the elasticity of painting as early as the late 1950s. Her series Wood Pictures expanded ideas around the general practice of painting but also the specific genre of landscape painting. Working with pieces of found wood, Thompson combined and assembled wooden fragments, using each piece as a gesture of the brush. Drawing upon her material’s natural grain, she punctuated the picture frame with her compositions that placed one grain strategically against the other. Her work also comments on the notion of place, with each piece of wood representative not only of its original source but also its connectedness to the larger whole. Thompson’s view on life was metaphysical, and she drew upon the principles of interconnectedness throughout her practice.

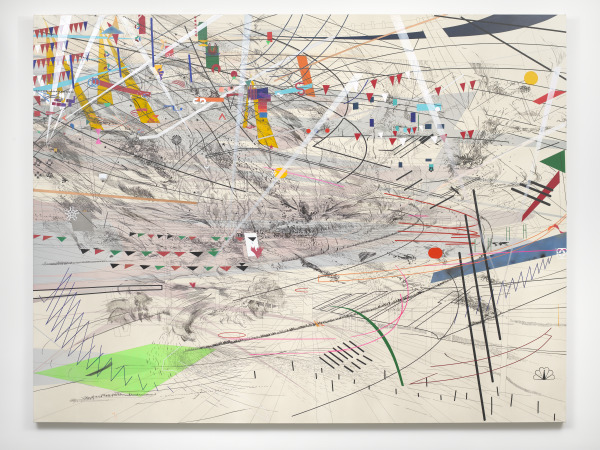

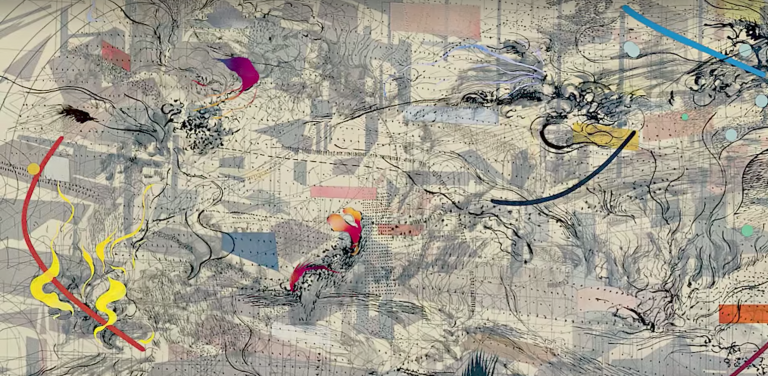

Stadia III, Julie Mehretu

“I’m interested in describing this as a system. . . a whole cosmos, and that is the overall painting, while the little minute detail marks act more like characters, individual stories. Each mark has agency in that sense—individual agency.”—Julie Mehretu

Mehretu’s monumental paintings address contemporary themes of power, colonialism, and globalism with dramatic flair. She adopts imagery from architecture, city planning, mapping, and the media. At the same time, her bold use of color, line, and gesture makes her works feel like personal expression.

Stadia III belongs to a series of three Stadia paintings dealing with the theme of mass spectacle. Conceived in the wake of the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, the series reflects Mehretu’s fascination with television coverage that transformed the war into a kind of video game—as many at the time commented—and in the spectrum of nationalistic responses that she witnessed during travels to Mexico, Australia, Turkey, and Germany. The series also reflects her interest in the international buildup to the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens.

DECORATIVE ARTS Galleries- Level 3

Lamp, Eileen Gray

In 1923 Eileen Gray designed a “Bedroom-boudoir for Monte Carlo” as part of the 14th Salon of the Society of Artists-Decorators. Among the carpets, tables, sofas, screen, and lighting fixtures was this floor lamp. It shows Gray’s skill in lacquer work as well as her ability to design furniture that was advanced for its time. The lamp, influenced by both South Sea Islands and African art, also exhibits futuristic qualities. It was acquired by the fashion designer Madame Mathieu Levy from Gray’s gallery called Jean Desert in Paris.

Covered Jar, Lucia K. Matthews

The Furniture Shop in San Francisco was a unique partnership between husband-and-wife Arthur and Lucia Mathews. Arthur was the chief designer of the shop and dealt with mural decoration, furniture, and interiors. Lucia carved, decorated, and painted furniture and other objects, such as this covered jar that she gave to her sister as a wedding gift. Although there are several versions of this jar, each one has a slightly different appearance.

Queen of Hearts (for Hous'hill, Catherine Cranston's residence, Glasgow, Scotland), Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh

Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, wife of Scottish architect and designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh, created numerous stenciled and gessoed pictures for the tearooms that her husband designed for Catherine Cranston in Glasgow. Later Macdonald Mackintosh assisted her husband in the interior decoration of Hous’hill, Miss Cranston’s Glasgow residence. These four panels, originally set into the walls of the Card Room in Cranston’s house, depict the queens of the four card suits flanked by two court pages. Macdonald Mackintosh’s use of gesso to create a high-relief linear style was characteristic of her work during the period.

Photography Gallery - Level 3

Georgia with Hibiscus moscheutos (Rose Mallow) (detail), 2018, Susan Worsham (American, born 1969), inkjet print. Courtesy the artist and Candela Books + Gallery. © Susan Worsham

Home/Grown: Photographs by Susan Worsham and Brian Palmer

September 16, 2024 – April 6, 2025

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts presents Home/Grown: Photographs by Susan Worsham and Brian Palmer. The exhibition showcases photography by two contemporary Richmond-based artists whose works explore the nexus of place, memory, death, and healing.

The photographs by Worsham are from her series Bittersweet on Bostwick Lane. In these images that explore loss and redemption, the artist attempts to come to terms with her brother Russell’s suicide. After that devastating loss, Worsham developed a close relationship with Margaret Daniel, an elderly neighbor whose touching memories of Russell and insights into life and death served as poetic inspiration for the artist’s photographs of children, landscapes, and still lifes.

Sculpture Garden

High as the Listening Skies and The Edges of Heaven, Rest, Jennie C. Jones

This immersive installation at VMFA features two sound works. The first composition, High as the Listening Skies, features three gospel choirs from Houston, Los Angeles, and Baltimore, performing the song “A City Called Heaven.” The song was popularized by gospel icon and civil rights activist Mahalia Jackson. The second featured work, The Edges of Heaven, Rest, is primarily tonal and associated with the concept of music as having healing energy. Jones layers audio samples—effectively collaging composition from Black composer Alvin Singleton.

The two works, which can be experienced together in the chapel located in the museum’s Sculpture Garden, create a striking balance between the crescendo of a spiritual ecstatic and a meditative calm. Interwoven, they emit a sonic framing that bridges the physical world to the ethereal realm, offering the transcendent and transformational possibilities of sound.

Related Videos

Julie Mehretu @ VMFA

4:12Artist Julie Mehretu talks about the concepts, processes, and implications of her "Stadia" series, including "Stadia III" in VMFA's permanent collection.

Artist Interview and Performance: Raven Custalow

4:01In 2020, Raven Custalow, Virginia Native artist of Mattaponi and Rappahannock ancestry and an enrolled member of the Mattaponi tribe, was commissioned by VMFA to create a feather-mantle titled Puttawus. This video shows the artist at work and performing while wearing the feather-mantle.

Esther Mahlangu @ VMFA

10:12South African Ndebele artist Esther Mahlangu discusses the early years of her paining practice, her designs and pigments, and the preservation of culture in this talk at VMFA. The conversation includes Esther Mahlangu, Marriam Mahlangu, Grace Masango, and Richard Woodward (Curator of African Art).

Howardena Pindell @ VMFA

56:45A conversation with the renowned abstract, multidisciplinary artist about her life and her work with Valerie Cassel Oliver of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and Naomi Beckwith of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago.

Collection Stories

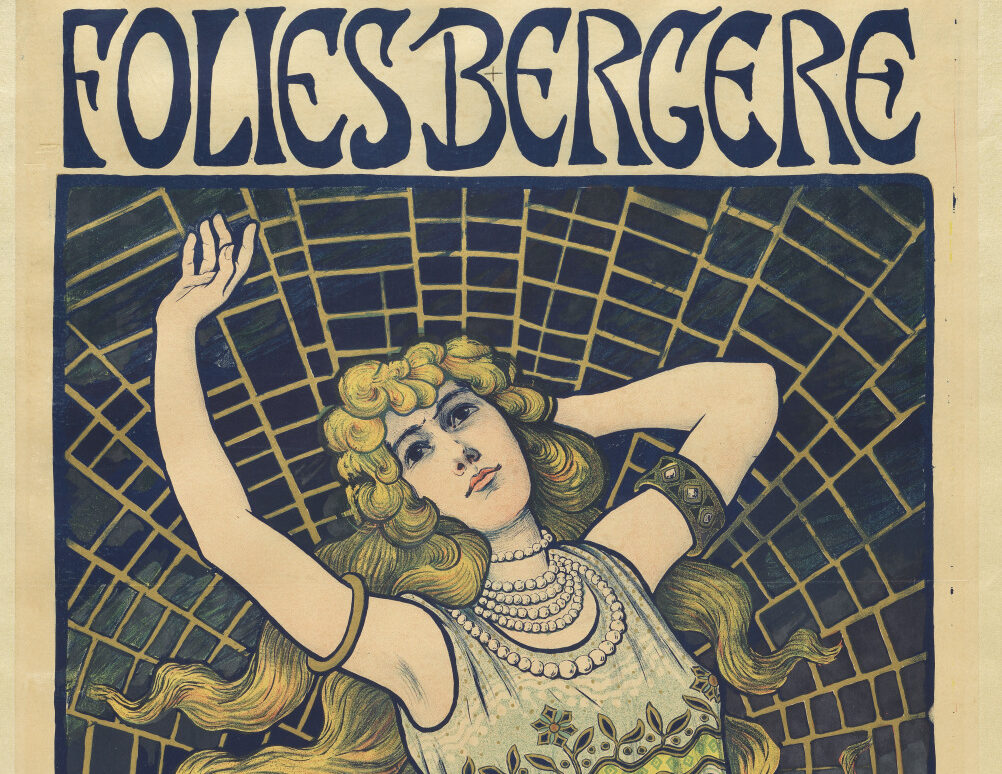

Staging Art Nouveau: Women Performing at the Turn of the 19th Century

Discover the incredible careers of female performers who became the first modern celebrities and learn how they broke beyond the social constraints placed on Victorian women, inspiring visual artists in the process.

Willie Anne Wright

Explore the life of Virginia artist Willie Anne Wright and discover how her innovative approach to artmaking and selection of subject matter offers new perspectives for looking at the world.

This Collection Story was created in conjunction with the special exhibition Willie Anne Wright: Artist and Alchemist (on view at VMFA from October 21 – April 28, 2024). This is the first museum exhibition to celebrate the full sweep of this artist’s remarkable career.

Gee’s Bend Quilters

Explore the quilts of Gee’s Bend and discover how they stand out for their flair – composed boldly and improvisationally, in geometric patterns and transform recycled clothes and other remnants into extraordinary works of art.

Additional Resources

Discover more ways to connect with the art by Women Artists on Learn!

For families:

Little Eyes Look: Bloodline: The Matriarchs by Holly Wilson

Los Ojos Pequeños Miran: Genealogía: Las Matriarcas, de Holly Wilson

At Home Art Activity: Art of the Still-Life